Georgian London: Into the Streets (26 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

Samuel Johnson once said the ‘

full tide of human existence

is at Charing Cross’. Here were the large coaching inns, including the famous Golden Cross, sending and receiving travellers from the West. Some idea of the size and concomitant racket is given by the fact that the ground floor of the Golden Cross held stabling for seventy-eight horses, as well as a bar and tap room for the coachmen, a farrier’s shed and a booking office. The entrance to the old inn was too low for the modern coaches, proving fatal at least once. In 1800, the coach leaving for Chatham bore, ‘

a young woman

, sitting on the top, (she) threw her head back, to prevent her striking against the beam; but there being so much luggage on the roof of the coach as to hinder her laying herself sufficiently back, it caught her face, and tore the flesh’. She died soon afterwards. The Golden Cross sat roughly where South Africa House is now, on the east side of Trafalgar Square. Travellers arriving here and at other coaching inns, such as the Greyhound, then took local lodgings. The wealthier ones lodged close to the court, in St James’s and Pall Mall; the less well off disappeared into Soho, or south of the Strand for the cheapest accommodation.

Where Charing Cross Station is today sat Northumberland House, a massive early-seventeenth-century house, commemorated by Northumberland Avenue leading down to the Embankment. Facing down Whitehall were the statue of Charles I and the pillory. On the north side of what is now Trafalgar Square, where the National Gallery now stands, was the Royal Mews, providing stabling for the King’s horses. The quality of housing available was fairly low and much of it was old and shabby, so socially the area was very mixed. The area south of Charing Cross was full of grand but rotting buildings, street and river traffic, and more of the Huguenot French immigrants.

One of the larger properties between the Thames and the Strand was Durham House, now commemorated in Durham House Yard. In 1632, Sir Edward Hungerford was born in Wiltshire. He inherited a fortune and, with it, Durham House. Heavy debts sustained at the

gambling tables left him unable to repair the mansion, and it fell into disrepair. However, the house had one huge advantage: the Hungerford Stairs, leading up from the Thames. It was a convenient place for traders to land their commodities to sell at the nearby Covent Garden market, to the north.

Small street markets were everywhere, but it soon became apparent that the densely populated area of Charing Cross and the Strand needed its own market. Edward Hungerford applied to the King for permission to establish a market on the site of Hungerford House. It opened in 1682, a thriving shopping-mall-type affair with a covered piazza. Unlike most London markets, Hungerford had no particular speciality. It sold fish, meat and all types of fruit and vegetables. After 1685, the area became very popular with the Huguenots, and the market was known for selling foreign foods.

There was a large meeting hall upstairs which, in 1688, the refugees established as Hungerford Market Church. It remained a church until 1754, when the market itself was already in decline. However, demand for a market in the area remained high, and so many people came and went via Hungerford Stairs that it limped on for another century, when Peter Cunningham, in his

Hand-book of London

, declared that it failed because it was ‘of too general a character and attempts too much in trying to unite Leadenhall, Billingsgate, and Covent-garden Markets’. Despite attempts to revive it, Hungerford Market failed and was eventually pulled down to make way for the development of Charing Cross Station, completed in 1864.

Very close to the Hungerford Market was the dwelling Benjamin Franklin occupied for sixteen years whilst working in the London print trade. He was fond of London, although he thought that his colleagues drank too much beer. He taught two of his colleagues to swim, and once swam from Chelsea to Blackfriars as a demonstration. On his first visit to London as a young man, he made a pass at his best friend’s girlfriend, a ‘

genteelly bred … sensible, lively’ milliner with her own shop. She repulsed him, and he noted the incident in his autobiography as ‘another

erratum

’. The Benjamin Franklin House survives as a museum at 36 Craven Street.

By the 1740s, the problem with Strand streetwalkers had become so pronounced that one night the constables of the watch, having drunk too much on duty, rounded up twenty-five women and stuck them into the St Martin’s Lane Watch House. Six of them suffocated to death overnight, including a laundress who had been caught up in the fray on her way home from work. St Martin’s and the surrounding area continued to be a rough area, largely dependent upon prostitution. In one court there ‘

were 13 houses

… all in a state of great dilapidation, in every room in every house excepting one only lives one or more common prostitutes of the most wretched description - such as now cannot be seen in any place’.

The walls of Scotland Yard, then filled with old wooden buildings, were

…

covered with ballads

and pictures … miserable daubs but subjects of the grossest nature. At night there were a set of prostitutes along this wall, so horridly ragged, dirty and disgusting that I doubt much there are now any such in any part of London. These miserable wretches used to take any customer who would pay them twopence, behind the wall.

Scotland Yard served as the way in and out of 4 Whitehall Place, which was the police headquarters after the formation of the force, in 1829. By the late Victorian period, the headquarters had spread into almost all the buildings surrounding the yard and so, in 1890, when they moved to Victoria, the new building was named New Scotland Yard.

Near the original Scotland Yard, Charles Dickens worked as a boy in Warren’s Blacking Factory on the Hungerford Stairs and describes the factory as a

…

crazy, tumbledown old house

, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscotted rooms and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise visibly up before me, as if I were there again.

By the time Dickens was working at Warren’s, the Charing Cross district was an eyesore in the heart of fashionable London. Lord Berkeley still kept his staghounds in kennels there. The Royal Mews, where the National Gallery now stands, stabled the King’s horses. Apart from the grand church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, the buildings and their tenants were poor, including small pockets such as ‘the Bermudas’, ‘the Caribbee Islands’ and, notably, ‘Porridge Island’ which Hester Thrale described as a ‘

mean street

, filled with cookshops for the convenience of the poorer inhabitants; the real name of it I know not’.

The makeshift nature of the area before the Trafalgar Square and Charing Cross developments is further encapsulated in the mystery of Bow Wow Pie.

Immediately in front of the Horse Guards

, were a range of apple stalls, and at twelve noon every day two very large stalls were set up for the sale of ‘Bow Wow pie’. This pie was made of meat very highly seasoned. It had a thick crust around the inside and over the very large deep brown pans which held it. A small plate of this pie was sold for three-halfpence, and was usually eaten on the spot, by what sort of people and amidst what sort of language they who have known what low life is may comprehend, but of which they who do not must remain ignorant.

Quite what the highly seasoned meat in Bow Wow Pie was, is sadly – or perhaps thankfully – lost to us now.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the area had become hopelessly run-down. The Prince Regent desired something better, along the continental model. John Nash set about devising a recklessly imprudent plan. He imagined a straight Regent Street, smashing through the existing, blurred borders of Mayfair and Soho and designed to ‘

cross the eastern entrance

to all the streets occupied by the higher classes and leave out the bad streets’. It would create a continental-style boulevard in the heart of the West End, leading from Carlton House up northwards to Regent’s Park, giving the rich of St James’s, Mayfair and the newly emerging Marylebone somewhere pleasant to stroll, sup and be seen.

The reality was a compromised street which was built piecemeal. It is most successful at its northern end. The clearance of Charing Cross began in 1820, but the Trafalgar Square development was to stall for years. The National Gallery, finished in 1838, is the square’s finest feature, yet even that is a compromise, built on the plot of the old Royal Stables and recycling some of the columns and decorative features from the demolished Carlton House. Trafalgar Square is a London landmark, but it is a stagnant place, robbed of its diversity and vivacity by a bad attempt at a Parisian street. Caught between a spendthrift prince and an architect of overweening ambition, one of the liveliest, if roughest, parts of London was cleared and left derelict. With the arrival of Charing Cross Station, one of the last remnants of old London was railroaded out of existence. Although Nash’s Regent Street development was ultimately compromised, his idea of corralling the ‘bad streets’ of Soho was successful, securing the area’s decline in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

We now leave behind the artists, artisans, soldiers, the English whores and French goldsmiths, the shoppers and travellers and head across Regent Street into Mayfair, London’s ghetto of the ‘higher classes’.

6. Mayfair

Mayfair takes its name

from The May Fair which moved here from Haymarket in 1686–8, occupying the space now covered by Shepherd Market and Curzon Street. The Haymarket was exactly that, dealing in tons of hay and straw for London’s many thousands of horses. Shepherd Market was named for the owner of the land, rather than any idyllic meeting of shepherds and their flocks, but the area remained rural. In the reign of George I, the May Fair was banned as a public scandal, and soon after that it was history. Instead, Mayfair was becoming dominated by the mansions on the north side of Piccadilly. Behind them, it was still mostly empty fields up to Oxford Street. This was the scene of some of the fastest growth in Georgian London; by the mid-eighteenth century, it was almost entirely built up, with grand townhouses and leafy private squares for the aristocracy and the fashionable set.

What had started in St James’s Fields quickly moved north of Piccadilly, the dividing line between Mayfair and St James’s. Mayfair residents were in town to play and to shop. Renting houses and apartments suited them well. Leases ranged from part of a single season to decades, depending upon the inclinations and pockets of both parties. Mayfair comprises seven major estates named mainly after the owners who developed them: Burlington, Millfield, Conduit Mead, Albemarle, Berkeley, Curzon and, of course, Grosvenor. The Grosvenor estate is the only one which remains in family hands today without having undergone major dissipation.

The building of these estates was sporadic and relied upon periods of boom, but the trade cycle of the century was frequently interrupted by war. The Treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, coupled with the arrival of George I on the throne created a sense of stability. This, in turn, encouraged a wave of building which would establish the West End. The rapid bricking over of Mayfair’s greenery caused consternation

amongst her more vocal intellectuals: ‘

All the Way through

this new Scene I saw the World full of Bricklayers and Labourers; who seem to have little else to do, but like Gardeners, to dig a Hole, put in a few Bricks, and presently there goes up a House.’

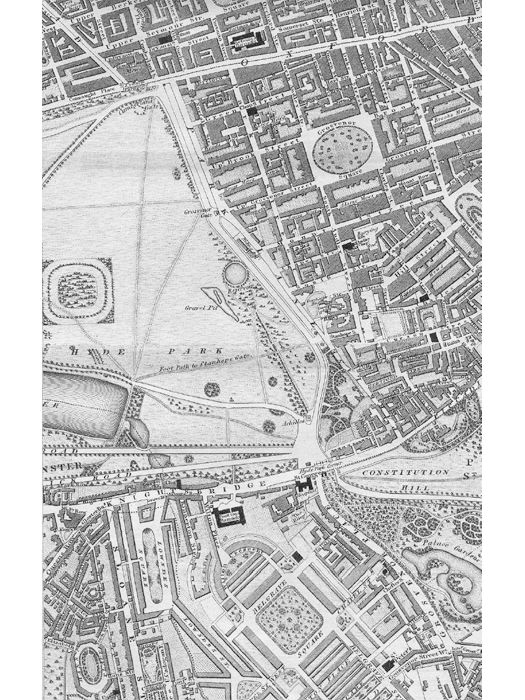

Mayfair, showing the main squares, detail from John Greenwood’s map, 1827

Mayfair was where a new breed of aristocrats emerged, buoyed by increasing wealth, obsessed by taste and reputation. They built some of London’s most spectacular houses and most beautiful garden squares. They cultivated art and refinement in a new way, creating eighteenth-century English style as we know it.

MAN OF TASTE

’

From 1660, mansions such as Clarendon House and Burlington House began to spring up on the north side of Piccadilly, but they were red-brick country houses and soon fell out of fashion. The next generation rebuilt them, but few men would so prominently yet unobtrusively influence London’s architecture as Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington. Like William Beckford, he inherited his father’s title at the age of ten. That was in 1704. When he reached his teens, Richard began to travel to the Continent on a series of grand tours. The ‘grand tour’ had evolved from a drunken tour of the Low Countries, to take in the cultural seat of Europe: Italy. Burlington adored Italy. He began to collect on a grand scale – and not just things, but also people. On a trip during his twenty-first year, he returned with a sculptor, a violinist, a cellist and some domestic artisans, as well as 878 crates of works of art, and two Parisian harpsichords.

Burlington loved, in particular, the works of Venetian architect Andrea Palladio and his Classical and severe style of building. In 1715, Scottish architect Colen Campbell published the first volume of his

Vitruvius Britannicus

. It was a catalogue of designs, including works by Jones and Wren. In the same year, Richard Boyle turned twenty-one and appointed Campbell as the architect of Burlington House, which was to be rebuilt and modernized. Burlington was by now a cultured and intelligent young man with a love for all things Italian,

including music. In 1719, he was one of the original contributors to the Royal Academy of Music; that summer, he conducted a lively correspondence, in French, with Handel on the subject of baroque opera. Burlington had found his feet as a patron of the arts.

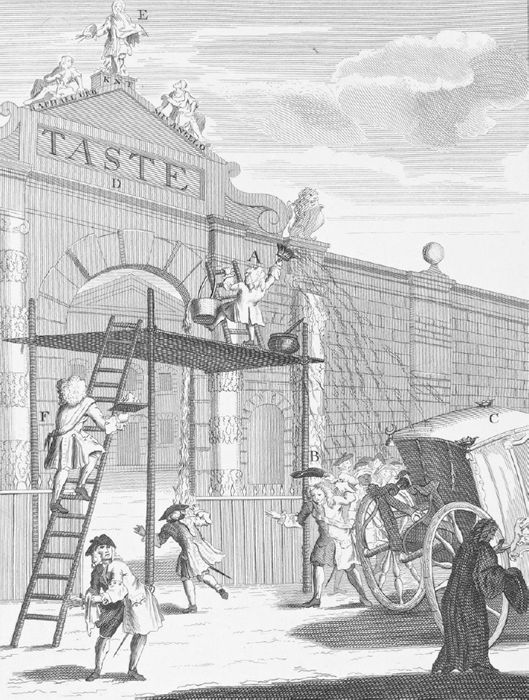

Burlington House gate, engraving from William Hogarth’s

The Man of Taste

, 1731. Alexander Pope stands on the scaffolding splashing paint on to the coach of the Duke of Chandos as Lord Burlington carries a plasterer’s float up the ladder

When complete, Burlington House was a triumph. Horace Walpole described it as ‘

one of those edifices

in fairy-tales that are raised by genii in a night’s time’. The house was an inspiration for the aristocrats who visited it, and many sought to emulate it. Burlington continued as a gentleman-architect, designing assembly rooms, houses for his friends, and even a dormitory at Westminster School. Palladian motifs – such as the Classical pediments above the porches, and the rusticated quoins on the corners of buildings – were soon seen all over London. They featured in books for gentleman-architects, and then in trade manuals for builders and carpenters. The ubiquity of the Palladian style in British architecture is clearly seen in the doorways and windows of most of the Edwardian office buildings along Piccadilly still standing today, testifying silently to Pope’s back-handed swipe at Burlington, whose simple but elegant building formulae had filled ‘

half the land

with imitating fools’.

HEIRESS OF A SCRIVENER

’: THE GROSVENOR ESTATE

The fields between Park Lane and Oxford Street came to the Grosvenor family in 1677, through the marriage of 21-year-old Cheshire baronet Sir Thomas Grosvenor to twelve-year-old Mary Davies. Mary was the ‘heiress of a scrivener in the City of London’ and holder of the Manor of Ebury, upon which most of Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico now sit. She, her mother and a not-quite-rich-enough-step-father were encumbered by the estate, which was deeply in debt. A fortuitous marriage was the only way out. The Grosvenors had money and a name but were small beer in terms of nobility. Mary had property but neither money nor breeding. The marriage produced two daughters and five sons before her husband’s death, aged forty-four.

The day before her husband was buried, Mary introduced her

family to Father Lodowick Fenwick, a Catholic chaplain. By September, Mary was planning a trip to Paris with various members of the Fenwick faction, including Edward, Father Fenwick’s brother.

What took place there

became known within the family as ‘The Tragedy’. On returning to London, Mary drew up a petition to Queen Anne alleging that Edward Fenwick and his brother, the chaplain, had lured her to a Paris hotel and drugged her ‘with a great quantity of opium and other intoxicating things’. Then, whilst drugged, she had been married to Edward. For the Grosvenor family, their children and myriad dependents, this was a disastrous turn of events. They sent agents to France, scouring for witnesses. Mary was declared a lunatic, probably to strengthen the case, and the marriage was finally annulled. She died in 1730; by 1733, her youngest surviving son, Robert, was the only heir. Two of his brothers had died in infancy, and the other two had inherited the title before dying.

Robert’s plans for the estate were grand. Grosvenor Square is the largest of all the Mayfair squares, and Colen Campbell was brought in to create a design for the east side. All the plots were taken by the builder John Simmons, who had a respectable stab at creating London’s first palace-front, a grand terrace of houses which looks like one enormous building. However, in 1734, the architecture critic James Ralph slammed it, even going so far as to call Number 19 ‘

a wretched attempt

at something extraordinary’.

Still, there was no shortage of takers. The wretched Number 19 was soon inhabited by the 7th Earl of Thanet, who parted with £7,500 for it (the equivalent of about £11 million now). Like most of the finest houses in the square, it was demolished in the twentieth century.

The nine-year-old Mozart

performed there, in 1764. And in the same year, the Adam brothers began to make improvements to the house. They were busy all over the square for years, providing work for a veritable army of builders and craftsmen. Most of the houses were built with mews behind, containing smaller houses for servants, as well as stabling and storage.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Grosvenor, nearby Berkeley Square and the surrounding streets were fully inhabited. Of the first 277 houses built on the estate, 117 (or just over 42 per cent)

were occupied by titled families. There was also a large ‘support staff’ taking up residence. In Brook Street there was an apothecary and a shoemaker, as well as a grocer, a cheesemonger and a tailor. In 1749, almost 76 per cent of the Mayfair voters in the Westminster election were tradesmen; they included builders, caterers, dressmakers, two peruke-makers and a stay-maker.

At the same time

, there were 75 public houses, inns and places to eat.

By the last decade

of the century, almost two-thirds of the 1,526 residents were involved in ‘trade’ – ranging from muffin-makers to dressmakers to a gentleman-architect – and all were dependent upon the voracious consumers amongst the aristocracy who, by the 1790s, dominated the area.

Boyle’s

court guide was first published in 1792, a hybrid of an A–Z and

Hello!

magazine, showing the London visitor which were the fashionable streets and where the serious players lived. Upper Brook Street was almost entirely dominated by the elite of the court circle, with 49 out of a possible 55 houses listed in the guide. The listings followed a strict sense of hierarchy, almost an aristocratic caste system.

The magnates

, or grandees, were at the very top, roughly 400 peers and peeresses who owned on average 14,000 acres each; below them were the great landowners at about 3,000 acres, and at the bottom were the country squires with at least 1,000 acres each. During the eighteenth century, many men rose to tremendous wealth through business. They tended to buy houses and country estates, yet often disposed of them during their own lifetimes when a better investment came along. For the aristocracy, holding on to a family seat for three generations or more conferred gentility, and a country seat gave a sense of permanence reflecting family standing. London, in contrast, was a hubbub of unknown potential and danger, artistry and fakery. The things the aristocracy stood for – culture, politics, gambling, scandalous sex lives and flashy wealth – were best suited to the urban landscape. The London Season, revolving partly around the sessions of Parliament, which ran from November until the summer recess, was also a whirl of shopping, visits, parties, exhibitions and recitals. For the two-thirds of Mayfair residents involved in servicing this four-month party, September must have been bittersweet.

As Mayfair became an increasingly covetable address during the eighteenth century, the success of the original speculation, and speculators, was assured. Yet all was not well within the Grosvenor family. Upon Robert’s death, his son Richard inherited. He was not a stupid man, but he had inherited little of his father’s good sense, and it wasn’t long before he began to gamble seriously. Gambling, however, was not to be the sum of his problems. In 1765, he found his wife, Henrietta, in flagrante delicto with Henry, Duke of Cumberland. Richard was thirty-eight, whilst the lovers were both twenty-four. He sued the Duke for ‘criminal conversation’, or adultery. It must have been pride which made the wealthy and handsome Grosvenor sue; he could not obtain a divorce, as Henrietta could prove him guilty of cheating too. Richard won and was awarded damages of £10,000. He and Henrietta separated in the high-profile case, leaving him free to continue as one of the ‘

most profligate men, of his age, in what relates to women’ and a ‘dupe to the turf

’.

In 1785, Richard was forced to hand over the estate to trustees, who administered it in order to pay his oceanic debts. He died, in 1802, from complications of surgery, with debts of £150,000 (about £120 million now). It was a sum only achievable by a man with an overweening love of horse racing and the gaming tables. Fortunately, the vast holdings of the Grosvenor estate had remained untouched, although cash was seriously depleted. By the 1820s, all the 99-year leases granted by Robert had begun to expire and his grandson, also Robert, began to consolidate an empire.