Georgian London: Into the Streets (41 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

Despite the charming streets around Christ Church, Spitalfields remained largely given over to warehouses and workshops, as well as the large Truman Brewery. London weaving was affected terribly by the introduction of the power loom. It also suffered through the wars with France, which affected the supply of raw silk, and re-export sales. As early as 1736, the Spitalfields weavers gathered in Moorfields to protest about standards of pay. In 1742, outsourcing to the provinces began. The Spitalfields weaving community was soon on a slippery slope into large-scale poverty.

A typical manufacturer would employ wage-earning weavers. During the early part of the century, there was an agreed list of piecework rates, which was kept in a ‘book’ and adhered to, more or less, by all manufacturers and master weavers. By 1767, the rates in the book were being undercut. Pressure from the provinces and the power looms was making London-manufactured goods increasingly unviable. Riots resulted, during which the weavers ‘

traversed the streets

at midnight, broke into the houses, and destroyed the property of the manufacturers’.

The book was reinstated and new rates negotiated. In 1773, Parliament granted the first Spitalfields Act, designed to force the weavers to agree piecework rates. Sadly, they were up against an economic decline so marked that there was little to be done. The weavers of Spitalfields battled on. The Act was extended twice, once to bring in all types of silk-mix materials, and the second time to include the

journeywomen often employed in the silk-ribbon trade and previously neglected. But almost all but the finest silk work had been driven out of London. One weaver, Stephen Wilson, kept ‘a book of lost work’ in which he lamented: ‘

They had driven away crape, gauze, bandanna handkerchiefs and bombazine in turn.’ The crêpe and gauze were now manufactured largely in Essex, the bombazine in Kidderminster and the bandannas in Macclesfield. A short time later, Wilson noted London had lost ‘all small fancy works

’.

By the early nineteenth century, London couldn’t compete with the far lower wages more provincial workers could subsist upon. This was particularly marked after the French Wars ended, when fashion became more fleeting, international and hungry for novelty. The Spitalfields model, as protected by the Acts, was even more outmoded. Other parts of the country struggled under fierce competition, yet the weavers of Spitalfields had their rates protected by law and the Justices. It was unsustainable; in 1824, an Act was passed which essentially left Spitalfields to the mercy of the free market. Poverty descended upon the area – a poverty it would not shake off for another century and a half.

London’s weavers could be dismissed as largely foreign, uppity and violent. But their skill as craftsmen, as well as the social and intellectual vigour which permeated Spitalfields, was unique. The atmosphere of endeavour and creativity, and the eternal prospect of poverty, created in Spitalfields an atmosphere of self-improvement more often associated with the later Victorian period. Many Huguenots were educated to a good level and continued to place a high value upon education. It was seen as by no means impossible for an intelligent man to learn the basics of almost everything there was to know.

Most of those who wished to continue their education and discover more of the world could not hope to join the Royal Society, which was really open only to the upper echelons of society. So a group of Spitalfields men decided to create their own society to hold experiments and feature lectures for the improvement of their members. In the eighteenth century, there were sharp divides between what was ‘scientific’ and what was not, and many wanted to explore that divide. The Spitalfields Mathematical Society was born.

This interest in finding out more about scientific advances, as well as promoting self-improvement, was significant amongst the humbler Huguenot weavers of Spitalfields. In 1717, John Middleton was a teacher of mathematics and a navy marine surveyor. He began, with a group of Frenchmen numbering around sixty, to meet at the Monmouth Head Tavern in Monmouth Street, near the building site that was Christ Church, Spitalfields. ‘

The Society met

on Saturday evenings and it is said that one of its rules was that any member who failed to answer a question in mathematics asked by another member was fined twopence.’ Middleton’s emphasis was on practical mathematics, and those who attended were relatively prosperous men – even if they were classed socially as artisan labourers.

A mathematical academy soon opened in Spital Square, and one of the masters, John Canton, went on to become a famous electrical experimentalist and Fellow of the Royal Society. Another member was the naturalist Joseph Dandridge, who began to design silk patterns based on scientific illustrations. Spitalfields became known as a place of educated trades and craftsmen.

From the late 1740s, the Mathematical Society invested heavily in scientific apparatus that was used for demonstrations. By the 1790s, this ‘cabinet of instruments’ had grown so large that it indicated the society was conducting demonstrations before considerable audiences. By 1804, it had a large library at the disposal of its members. To belong was a mark of both education and sensibility.

Towards the end of the century, the proportion of weavers in the society began to fall, and the number of gentlemen rose. What remained was the society’s commitment to public education. From the middle of the century, weavers comprised about 40 per cent of the subscribers, but they were increasingly supplanted by chemists, druggists, apothecaries and seedsmen, as well as distillers, dyers, brewers, sugarmen, ironmongers, instrument makers and teachers.

The Mathematical Society was the first and most important of all the Spitalfields societies. A resident of Spital Square for over thirty years reminisced:

South of Spitalfields, in Whitechapel, there were many French-descended weavers, but another type of textile-dealing immigrant was more prominent on the local streets. Jewish dealers in second-hand clothes were traditionally situated in Whitechapel and dominated the local population. From there they could easily make it to Rag Fair, near the Tower of London, to ply their trade; and their accommodation remained cheap, yet was within striking distance of the City synagogues.

These dealers, often working in family groups, offered ready money for clothing that was worn out, or no longer wanted, which they then sold on to others who could use it, for industrial or recycling purposes. Samuel Taylor Coleridge had a curious story to relate about an Old Clo’ Man he met in the street, showing how those who used street cries were adopting an accepted, yet indistinct ‘patter’. Coleridge was so irritated by one Jewish man’s cry of ‘Old Clo’ that he snapped at him. The man

…

stopped, and looking very gravely

at me, said in a clear and even fine accent, ‘Sir, I can say “old clothes” as well as you can; but if you had to say so ten times a minute, for an hour together, you would say Ogh Clo as I do now;’ and so he marched off … I followed and gave him a shilling, the only one I had.

The Jewish population of Whitechapel was distinctive in that, unlike Spitalfields, there wasn’t a coherent band of workers, and very few

masters. The vast majority of the Jewish population just ‘got by’, working as hawkers, pedlars and dealers. By the beginning of the Victorian period, they numbered over 15,000.

St Mary Matfellon Church, at the heart of the area, became known as the White Chapel during the medieval period due to its white-washed exterior, giving the district its name. In 1711, Brasenose College, Oxford, purchased the right to appoint a priest of their choosing there.

After 1715, the Rector

fell out with the Dean and painted his likeness over the character of Judas in the painting depicting the Last Supper, above the altar. He annotated it helpfully with ‘Judas, the traytor’. The Dean pretended not to notice, and the Bishop of London ordered the picture removed and repainted. St Mary’s was destroyed in the Blitz and never rebuilt, like much of Whitechapel.

When John Strype revised Stow’s

Survey of London

, in 1720, he described Whitechapel as ‘a spacious fair street, for entrance into the City eastward, and somewhat long’. The area housed many successful medium-sized businesses, such as the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, founded in 1570 (and Britain’s oldest continual manufacturer). By the eighteenth century, the foundry was exporting bells to the Americas, including the Liberty Bell, in 1752. The Liberty Bell left England bearing a biblical inscription which would have been familiar to both the French Protestants who had sought refuge only a stone’s throw away, and also the Jews who worshipped close by. It came from the book of Leviticus 25: 10: ‘Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.’

Further out again from the rapidly filling Whitechapel was Mile End. Mile End, named for being one mile from Aldgate, had long been a settlement on the road to Colchester. At the beginning of the Georgian period, plans were made for a newer settlement closer to Spitalfields. Mile End was divided into Old Town and New Town. Old Mile End is now covered by the modern Stepney Green conservation area. It was one of the earliest country retreats for Augustan and Georgian bankers and the more prosperous members of the maritime community, including the Scandinavian merchants who had profited so handsomely from the demand for timber created by the rebuilding.

In 1696, a Danish-Norwegian Church was constructed in Wellclose Square, by which time the square was already neat and prosperous. Just to the east, in Princes Square, a Swedish Church was completed in 1729, as the area was popular with Scandinavian merchants trading in the City.

But by the 1760s, the area was losing its prestige. The arrival of the sickly-smelling sugar refineries pushed the more respectable residents out. The sheer volume of traffic using the Port of London meant that sailors were swarming through streets and squares which had previously been so genteel. The Scandinavian merchants moved out and, in 1816, handed their church over to trustees so that it could be used as a charity base to benefit seamen from their own countries.

In contrast, Mile End New Town, to the west, was on the rise. In 1717, John Cox and John Davies declared they were in possession of ‘

diverse Lands

in the hamlet of Mile-End new towne’ and they set about draining what had been known as the Hares Marsh, intending to create a smart new community. Early attempts to install public amenities weren’t without hiccups: in February 1718, James Withy was caught with a bag containing ‘

25 Fountains of Lamps

of the Convex-Lights’ from the Mile End New Town High Street. Mile End New Town, despite such setbacks, continued to flourish. In the 1780s, it was a model of civic planning, creating a workhouse and providing funds for lighting and patrolling of the streets. It was just close enough to Spitalfields to thrive, and it avoided the decay which was already setting into Stepney.

Stepney would continue to decline, and although much of the Georgian village survived the Blitz, it was swept away in the improvements of the 1950s as London’s planners drove all before them in the prolonged fit of barbarity which buried so much of the eighteenth-century city under concrete.

11. Hackney and Bethnal Green

Hackney is one of the largest parishes in London. The marshes alone covered 335 acres at the end of the eighteenth century. The parish itself stretched from Stamford Hill in the north to Cambridge Heath in the south. It began in the west at Shoreditch workhouse, and terminated in the east at the boundary with the parish of St Matthew, in Bethnal Green. Within Hackney, the hamlets were Clapton, Dalston, Homerton, Shacklewell and Kingsland. Throughout the eighteenth century, most of the land was turned over to farming, with a small proportion of market gardening and horticulture, concentrating mainly on ‘exotics’. It was a community where cattle were raised on the lush pastures, and where Samuel Pepys saw trees of oranges ripening in the sun. South of Homerton High Street were extensive watercress beds. The area was attractive, with small pleasure gardens, pubs, ponds for swimming and fishing, and pleasant open spaces within striking distance of the City.

For centuries, Hackney had been served by St Augustine’s Church, built in 1253 – at the same time as the parish was mentioned in Henry III’s state papers. From 1578, the Black and White House sat beside the church, serving first as a grand private home for a merchant of the Muscovy Company and then for many years as a boarding school for girls before being shut down and demolished at the end of the eighteenth century. By then, it was clear that St Augustine’s would not do. In 1789, St John-at-Hackney was built to hold 2,000 parishioners. The nave of St Augustine’s was demolished, leaving just the tower standing. The ancient settlement had given way to the modern, just as Hackney’s pastures were giving way to the brickfields of Kingsland and the encroaching streets.

Hackney had long been famous for its quality of education. In the Elizabethan period, many intellectuals made it their home, and various highly regarded schools were established over the next centuries.

Sir John Cass, whose family moved from the City to South Hackney to escape the plague, left money for the education of ninety boys and girls. Forty years after his death in 1708, the Sir John Cass Foundation was formed to continue his work. Various John Cass institutions still remain in London, forming part of the London Metropolitan University, the John Cass School of Art in Whitechapel and the John Cass School of Education in Stratford.

Throughout Hackney there were also the ‘dissenting academies’, which arrived in the late seventeenth century to provide a grammar school-type education to boys from dissenting religions, such as Calvinism and Unitarianism, who would not be admitted to Oxford or Cambridge – or subsequently to the mainstream clergy or education system as teachers and tutors. Dissenting academies were particularly important in the encouragement of independent thought in London during the eighteenth century and eventually in the formation of the Victorian Nonconformist movement. Many of the boys educated in these schools became ministers and missionaries who would go on to represent their churches throughout the world.

The earliest of the academies were small, private establishments attached to the households of wealthy dissenters. Many were located around Newington Green, where ‘

Protestant nonconformity

and London commerce … featured strongly in local society’. Stoke Newington, a convenient three miles from London, had long been a favoured place for wealthy merchants to keep a country house. It had a small population, occupied locally in farming and market gardening. It was a pleasant and private place in which to found a small dissenting academy of ten or so pupils.

These academies were dependent upon the tutor, usually well known in his field, and the patron who made the space and funds available. One of the most prominent of these academies was run by Thomas Rowe from 1678. In his book called

The Nonconformist’s Memorial

, Edmund Calamy wrote that Rowe had ‘a peculiar talent of winning youth to the love of virtue and learning, both by his pleasant conversation and by a familiar way of making difficult subjects easily intelligible’. As was typical of these small colleges, it closed when Rowe left for America, in 1686, eventually becoming Vice-President

of Yale. Amongst his pupils were Daniel Defoe, Samuel Wesley (father of John) and Isaac Watts, who would return to Hackney and help design Abney Park with Lady Mary Abney (which was transformed into a non-denominational cemetery, in 1840). At the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth, dissent became more tolerated, and the academies could grow.

Hoxton College, another dissenting academy, had already existed in previous incarnations in Moorfields and Stepney before becoming established in Hoxton, in 1762. It adhered to Calvinist teachings and had a strong scientific curriculum. Several of the tutors were Fellows of the Royal Society, and the young William Godwin (1756–1836), later the radical writer and husband of feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, was a student there.

The Hackney academy, founded in 1786 and called New College, was also of particular note but did not last long. It occupied what had been Homerton Hall and provided a liberal and broad-ranging education regardless of religious belief. It had been founded in the London Coffee House on Cheapside one December evening, in 1785, when a group of thirty-seven Protestant City men decided to create a school which would focus on intellectual excellence. The college was an instant success, thriving in the atmosphere of religious tolerance which followed the Gordon Riots. It was, however, soon associated with radicalism and sedition. This was something the college seemed to encourage: they invited Thomas Paine as their after-dinner speaker only weeks after he was charged with seditious libel for

Rights of Man

. In 1794, William Stone, a governor of the college, was arrested on charges of high treason. He had allegedly been passing information to the French Republic. Although he was eventually acquitted, his trial sounded the death knell for the dissenters’ college. By 1796, it was closed, after a decade of huge success. Joseph Priestley – the theologian and philosopher, and the man responsible for the discovery of oxygen – had been a popular tutor. The critic William Hazlitt had been a pupil, amongst many other young men who went on to play significant roles in early nineteenth-century life in Britain. Hazlitt wrote to his father in 1793, recording his weekly expenses at the school, which included ‘

a shilling for washing

; two for fire; another shilling for tea and sugar; and now another for candles, letters etc.’. The closure of the school marked the beginning of Hackney’s slow decline from its eighteenth-century heyday. Today, the Jack Dunning Estate stands on the eighteen-acre site of New College.

At the time of New College’s short reign, industry began to move in, attracting large numbers of unskilled migrant workers in need of accommodation. The River Lea had always been navigable, and at Hackney Wick there were wharves where goods came and went. In 1780, the Berger family arrived and began to manufacture and refine paint pigments. (Two centuries later, their business was absorbed into Crown Paints, in 1988.) Hackney saw the manufacture of silk, printed calico, boots and shoes, and finally the very first plastics, before the local industries died altogether under the crush of population.

Nearby Bethnal Green remained rural for longer than Hackney. It was further out, around two and a half miles north-east of St Paul’s Cathedral, and for a long time it was part of Stepney. Dairy farms flourished there. In 1743, the hamlet was created a parish in its own right. Like Hackney, most of the origins of the hamlet were Tudor and rather grand, with impressive manor houses dotting the open fields. The south end of the parish sat partly on Hares Marsh and Foulmere, with a causeway known as Dog Row. Along the edges of Bethnal Green, cattle and carriages flooded into London from Essex, resulting in broken pavements and ‘

heaps of filth

… every 10 or 20 yards’. Old Bethnal Green Road had previously been known as Rogue Lane, and was still called Whore’s Lane as late as 1717. In 1756, Bethnal Green Road, just to the south, replaced it as the main thoroughfare.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Bethnal Green was beginning to house a poorer sort of inhabitant. The large Tudor manor houses were being subdivided into tenements or let as private asylums. Then, from the 1760s, a building boom took hold and hundreds of small houses, with frontages anywhere between thirteen and nineteen feet, were thrown up using local bricks. They were to house the weavers of Spitalfields, who were gradually moving east and were

mainly concentrated in the south-west part of the parish.

In 1751, Bethnal Green village

had only contained around 150 dwellings. By the early 1790s, the parish of Bethnal Green had gained around 3,500 new houses.

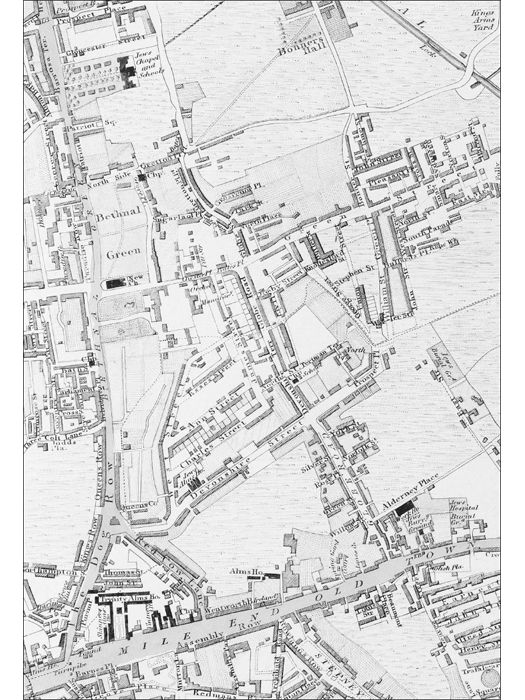

Bethnal Green, detail of map by John Greenwood, 1827

In the 1790s, boxing became a popular sporting feature of the area. The Jewish boxer Daniel Mendoza lived there when he became the English heavyweight champion, between 1792 and 1795. He lost the title, in 1795, to Byron’s boxing tutor, John Jackson. A charismatic and popular local figure, Mendoza ran a pub in Whitechapel, then turned to teaching boxing to supplement his income. York Hall, on Old Ford Road, is one of Britain’s most well-known boxing venues, continuing the tradition of the sport in the area. Mendoza’s thirty years in Bethnal Green represent its move from a solidly middle-class area, to a working-class one, populated by people of English, French and Jewish origin. The wealthier residents retreated from this torrent of incomers, and from the pockmarked landscape which brick-making and building had created in what had been open countryside.

From 1800, the construction

of Globe Town to house weavers who worked from their own homes, rather than in the dying factory system, further changed the landscape of Bethnal Green. Thousands of poorer weavers came to occupy Globe Town in the last decades of the Georgian period, with up to 20,000 looms working in the area.

Hackney and Bethnal Green were altered dramatically during the Georgian period. Such turbulence also created the two recurring themes of these neighbouring areas: violence and madness.

Many roads from the east passed through the large parishes of Hackney and Bethnal Green. Traffic was a fact of life. Much of it was cattle heading to Smithfield, or traders coming and going from the City. The long gaps between the hamlets meant the roads were dangerous at night, and the long distances between neighbours saw an early rise in crimes against property.

Highway robbery rose dramatically after the Restoration. The reasons are straightforward: people were moving around more, carrying cash and wearing valuable accessories. The rise in business travel meant lone men were more likely to have money on them, not just for transactions, but for subsistence. In the early 1700s, banknotes were still relatively untrustworthy, and coins were king. The lonely roads of Hackney, where many came and went from East Anglia and the north, provided rich pickings for men who could arm themselves and had a taste for danger.

Quaker Francis Trumble

turned to highway robbery, in 1739, when he accosted Thomas Brown on a footpath through a cornfield in Hackney. First, he asked Brown the way to Newington, but then, after Brown had directed him and turned away, he finally summoned the courage to begin the hold-up. Trumble had a pair of pistols and demanded money from Brown, who handed over about ninepence. He also took Brown’s silver pocket watch. As Trumble took off towards Hackney village, Brown shouted for assistance. Villagers nearby began a chase that lasted over three-quarters of an hour. They included Edward Dixon, who was standing drinking outside a pub with a friend. He found Trumble hiding under a hedge at the edge of Hackney Downs. Trumble threatened to shoot, and took off again towards the Kingsland Road, ‘through an Orchard, into a large Field of Beans and Peas’. Dixon finally ran him down, at the head of what had become a ‘thick’ crowd. Trumble, cornered, threatened them again with his pistols but finally agreed to give himself up to the man ‘in his own hair’, the wigless Dixon. Dixon took him to a nearby ‘Publick house’ where he noted Trumble ‘behaved very well’, and turned him over to Justice Henry Norris.

Norris was Henry Fielding’s counterpart in Hackney, serving as Justice for a long period and overseeing a period of substantial change in both the local area and the nature of London crime itself. Norris used The Mermaid Tavern in Mare Street as his base, although this wasn’t always to the liking of the landlord who, in 1738, refused to ‘store’ prisoners Norris wanted to commit for trial. The Mermaid still stands at 364 Mare Street, although it closed as a pub in 1944 and is now Mermaid Fabrics, a haberdashery.

Norris committed Trumble for trial at the Old Bailey, where Dixon testified that when he had confiscated Trumble’s pistols, they had contained nothing but bullets and paper wadding, with no charge. His threats to shoot had been mere bluff. The Old Bailey heard how both Trumble’s parents had killed themselves – his mother by hanging, and his father by drowning himself. His father’s suicide, only weeks before Francis Trumble took to the road, appeared to have been the trigger for his crime. Witnesses testified that, in the weeks leading up to the robbery, Francis had been increasingly melancholy and distracted. He refused to answer the door when worried friends called at his house in Hackney, and he had a ‘wildness’ in his eyes. After his committal to Newgate, his fellow prisoners kept him on suicide watch, successfully defeating his attempts to cut his own throat and to hang himself. The court found him guilty, on the basis that he was conscious of the difference between right and wrong. On 18 July, he was sentenced to hang. Nine days later, he secured a royal pardon. What became of him after that is not known.