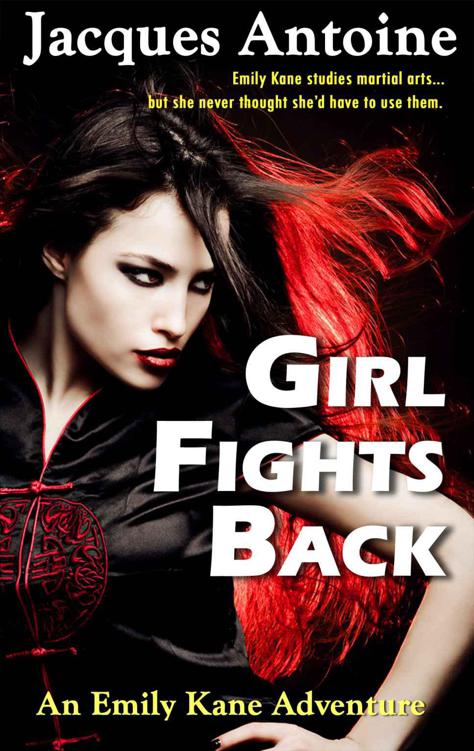

Girl Fights Back (Go No Sen) (Emily Kane Adventures)

Read Girl Fights Back (Go No Sen) (Emily Kane Adventures) Online

Authors: Jacques Antoine

Girl Fights Back

, by Jacques Antoine

Copyright 2011

Jacques Antoine

All rights

reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any

electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer,

who may quote brief passages in a review.

To Roxie and Miki,

for taking the initiative

.

Girl Fights Back

a novel

by Jacques Antoine

Chapter 5: Getting out the Door

Chapter 6: If you can’t stand the heat

…

Chapter 10: A Meeting on the Road

Chapter 12: Students Everywhere

Chapter 14: Back to the Woods Again

Chapter 21: A Foot in the Door

It’s like a kid swinging a bat in

his first little league baseball game. He has no idea what to expect, when to

begin his swing, when to commit to it completely, not to mention where to swing

the bat. Sure, he’s probably already practiced swinging at balls with his dad

out on the local ball field or at a batting cage. He knows how to hold the

bat—dominant hand on top, knuckles of both hands lined up, bat off his

shoulder—maybe even how to step slightly into his swing, shift his weight

to his back foot, swivel his hips and then his shoulders.

But facing the opposing pitcher in

a real, live game; now that’s something completely different. That kid on the

mound is not trying to teach him how to hit the ball. He’s throwing as hard as

he can, trying to get him out. His throwing motion is different from his dad’s.

It’s really hard to see the ball until it’s almost too late. His eyes don’t

focus on the right things; they don’t look in the right directions. He doesn’t

know what to look for. He closes his eyes and swings. Here’s what it sounds

like in sequence: thud... swish. Thud (the ball hits the catcher’s mitt), then

swish (the bat cuts the empty air). Later, after a lot more experience in game

conditions, he learns how to train his eyes to look and his mind to attend to

the right things.

That’s how sparring always seemed

to her: just a matter of seeing, of knowing where to look and what to look for.

She saw the telltale signs of her opponent’s intentions almost as soon as he

had formed them, certainly as soon as he committed to them. This was her third

martial art. First was

aikido

, a

beautiful, meditative discipline. All round, soft movements, deflecting the

opponent, but also absorbing him, enfolding him in the subtle folds of her own

movements, a caress, a rebuff... almost a kindness. Soothing the opponent,

allowing him to expend his energy fruitlessly, turning him around, twisting him

in an unexpected way. Perhaps he sees his effort is going awry even as it’s

happening to him, but there’s nothing he can do about it. The surprise she saw

written across his face gave a supreme satisfaction, better than victory and

his admission of defeat. Tap.

Then came

Shotokan

karate. This too was meditative in its own way. But also

much more angular, lots of jagged edges for an opponent to stumble on. Here, it

wasn’t so much a matter of absorbing, deflecting and twisting away as of

slipping inside and attacking her opponent’s attack from within. It was a new

way of looking at her opponent. Now, instead of looking for clues to the

ultimate destination of the attack and then derailing it, she learned to

examine the beginnings of his movements. What did they betray? How did he make

himself vulnerable at the very moment of his attack?

She would strike him just as he

began to strike her, but more quickly. A reverse punch to the solar plexus, or

perhaps a sharp knuckle to the inside of his bicep before he could even

straighten out his arm, or even a quick jab to his armpit. Instead of

retreating from him she stepped forward to meet his punch. She was so close he

couldn’t even reach her with his long arms! She didn’t hit him as hard as he

wanted to hit her, but it was hard to breathe after she hit him. It was

infernally frustrating, and puzzling. How did she know? She always seemed to

know!

That’s the way it always was with

boys. They tended to be bigger and stronger, usually faster, too. But they were

fascinated by their strength and it distracted them from the truly important

lessons. They absorbed all the techniques designed to make them strong and

fast, they broke boards, they wore their knuckles raw punching the heavy bag.

But it was much harder for them to understand the importance of learning to

see, to look. Sensei would drone on interminably about becoming still inside,

breathing in and out, feeling everything—not just the sweat on your

opponents brow and the little jitter in his chest—feel that, too, of course,

but so much else in addition. Feel the stillness every blow interrupts. Feel

the return of the stillness afterwards. There was just no room in a boy’s soul

for this lesson. Not yet. Maybe later. But she learned it all.

The strength and speed techniques

fascinated her at first, too. She wanted to be strong. She preferred kicking.

She was so much more flexible than the boys; it gave her what seemed like an

advantage. Learning to punch was cool, too. But she could never punch as hard

as she could kick. So she practiced as much as she could, in between schoolwork

and housework. But even though she was better and sharper than the boys at

kicking, she wasn’t better enough. She got a lot of bruises when they got a

punch or a kick in. They were embarrassed to hit her, but she got hit. She

would block their punches, too, but it still hurt.

One day she was looking one of the

boys in the eye over her gloves. He tried to look her eyes away. He wanted her

to see his left foot twitch so she would move to block it, leaving him an

opening for a left jab. It had worked before against others, even her. It was a

good move. It was supposed to just graze her chin. He would follow with a quick

front kick to her left knee and then as she was falling to the mat he would finish

her with a right hook to the left side of her face and a ridge-hand to the

throat. He knew he had to be fast, because she was limber and could easily land

one of those sneaky kicks to the side of his head as he leaned in with that

first jab. That’s why he wanted her to commit to a downward block before

committing himself to that first jab.

But she saw something else this

time as she watched him. She was all electricity, waiting for a sign in his

muscles she could react to, anticipate. Her synapses were poised to fire, a

state of high dynamic tension flowing out to her extremities and back again to

her core. She could feel the pattern, in and out, resonant, surging like a tide

of electricity. Her eyes examined him, looking in his eyes, at his shoulders, his

throat, his mouth (the muscles of the jaw sometimes twitch just as someone

makes a decision). His nerves resonated with energy like hers, though not

perhaps in sync with her.

Then it dawned on her: what she

sought was not to be found in any of those places. There was something else,

some

place

else to look. Her

attention slipped past his eyes, behind them, to something vital flowing behind

his eyes. His

qi

(or

chi

). She could feel it. She knew

instantly what he meant to do. Not in so many words. But she knew, she felt

with absolute confidence that she would recognize exactly when he had decided

to make his move, and what direction it would go to and come from.

He flicked his eyes down, twitched

his leg and waited for her to block. She did and he leaned in with his jab.

Before he knew what had happened, she had stepped just inside his fist. He

grazed her ear as she punched him hard to the center of his chest. He thought

of kicking before she hit him again, but her left knee struck just above his

knee as he fell backwards. She hit his chest, throat and chin three more times

before he hit the floor. Jaws dropped around the room. Everyone in the dojo

stood staring. They all recognized at once that she had just made a quantum

leap in her sparring. They sensed it, even as it came to pass, even though they

had no idea what it really meant.

Sensei smiled, drew her aside and

said quietly so only she could hear, “You hit him too hard. It left you

overcommitted.”

“I know,” she said, and she did.

She understood perfectly. He didn’t mean she had made a tactical error. There

was no flaw in her technique. But she had overcommitted emotionally. In the

thrill of the moment of insight, she had allowed herself the satisfaction of

hitting him as hard as he had meant to hit her. But it left her out of balance

emotionally, no longer sensing the flow of

qi

in the room. She gave herself over to the boyish thrill of hitting hard and

fast, of triumphing. It took an extra instant to pull herself back, to collect

herself emotionally, to open herself again to the energy of the room. Soon, she

would learn to control even that reaction.

From that moment on, no one in the

dojo ever managed to score a point on her again. Not even Sensei. The weekly

sparring competitions took on a different flavor for the others. She cast a

shadow over every match. They all knew the winner might eventually have to face

her. And there was something unsettling about it, a peculiar mix of

embarrassment and frustration. Her ability to read them was uncanny. None of

them quite knew how she always came out the winner, how she beat them to their

own punch. She never retreated, no matter how ferociously they charged. She

never let their size or strength faze her. She never allowed them to make any

use of their apparent advantages.

She saw what they did not see, felt

what they did not feel, because she looked where they did not look. It was, in

fact, a new way of perceiving, of being in the world. It changed her whole

life. When her dad picked her up in the family car, he knew. It was obvious on

that first day. She walked like a tomboy, as usual. Her strong shoulders and

quick legs looked the same as always. But she held her head at a slightly

different angle. Her father noticed.

Her hands were stronger and coarser

than one might expect in a girl, but not as large as a boy’s. If a boy with a

crush on her—she was quite pretty in her way, though she seemed to have

little interest in exploring that side of herself—tried to hold her hand,

he might not notice how different her hands were, what they could do in the

dojo.

But she could tell from his hands

exactly what he was capable of, that and the look in his eyes. Physical

strength, fighting strength, is more evident in a boy’s hands than in his arms

or shoulders. That’s where she could see if he had been trained. But the eyes

really said it all. Where did he look, what did he notice? Was he capable of

pulling back from visual immediacy and attending to something beyond, behind,

to

qi

? It seemed to anyone else like

an almost unfocused gaze. She never saw it in any of the boys she met.

In fact, the only people she knew

who looked in that way were Sensei and her father. With Sensei, it felt almost

like a secret they shared, even though he spent plenty of time trying to get

his other students to look in that way, too. But none of them had been able to

follow him. Sensei understood. That was the way it always was. He offered his

wisdom to them openly, without reservation, but none of them knew how take

advantage of his most important lesson. In fact, she was only the third student

in forty years to understand. Three was a lot, as he figured it.

With her father she never talked

about it. He encouraged her interest in the martial arts. He celebrated her

successes. But he remained curiously distant from the concrete reality of it.

Yet she never doubted he looked in the same way she did, saw what she saw, held

his head at an odd angle. They shared that, even if they never spoke of it.

Finally, she took up

kung fu

. She had already mastered two

other martial arts, so there weren’t any technical challenges for her here. She

just wanted to learn how to think and sense in a new way.

Kung fu

turned out to be a bit of an amalgam of all sorts of other

arts, kind of an encyclopedic discipline. It did not pretend to any deep unity,

as if the ancient monks thought to themselves: “Any of these techniques can

lead to inner peace. Study them all or only some of them. But the point is not

the mastery of any of them. Rather, keep studying them until you find the way

past them.”