Girl, Interrupted (6 page)

Authors: Susanna Kaysen

“Acting out,” the nurses said.

We knew what it was. The real Lisa was proving that Lisa Cody wasn’t a sociopath.

Lisa tongued her sleeping meds for a week, took them all at once, and stayed zonked for a day and a night. Lisa Cody managed to save only four of hers, and when she took them, she puked. Lisa put a cigarette out on her arm at six-thirty in the morning while the nurses were changing shifts. That afternoon Lisa Cody burned a tiny welt on her wrist and spent the next twenty minutes running cold water on it.

Then they had a life-history battle. Lisa wormed out of Lisa Cody that she’d grown up in Greenwich, Connecticut.

“Greenwich, Connecticut!” She sneered. No sociopath could emerge from there. “Were you a debutante too?”

Speed, black beauties, coke, heroin—Lisa had done it all. Lisa Cody said she’d been a junkie too. She rolled her sleeve back to show her tracks: faint scratches along the vein as if once, years before, she’d tangled with a rosebush.

“A suburban junkie,” said Lisa. “You were playing, that’s what.”

“Hey, man, junk’s junk,” Lisa Cody protested.

Lisa pushed her sleeve up to her elbow and shoved her arm under Lisa Cody’s nose. Her arm was studded with pale brown lumps, gnarled and authentic.

“These,” said Lisa, “are tracks, man. Later for your tracks.”

Lisa Cody was beaten, but she didn’t have the sense to give up. She still sat beside Lisa at breakfast and Hall Meeting. She still waited in the phone booth for the call that didn’t come.

“I gotta get rid of her,” said Lisa.

“You’re mean,” Polly said.

“Fucking bitch,” said Lisa.

“Who?” asked Cynthia, Polly’s protector.

But Lisa didn’t bother to clarify.

One evening when the nurses walked the halls at dusk to turn on the lights that made our ward as bright and jarring as a penny arcade, they found every light bulb gone. Not broken, vanished.

We knew who’d done it. The question was, Where had she put them? It was hard to search in the darkness. Even the light bulbs in our rooms were gone.

“Lisa has the true artistic temperament,” said Georgina.

“Just hunt,” said the head nurse. “Everybody hunt.”

Lisa sat out the hunt in the TV room.

It was Lisa Cody who found them, as she was meant to. She was probably planning to sit out the hunt as well, in the place that held memories of better days. She must have felt some resistance when she tried to fold the door back—there were dozens of light bulbs inside—but she persevered, just as she’d persevered with Lisa. The crunch and clatter brought us all scampering down to the phone booths.

“Broken,” said Lisa Cody.

Everyone asked Lisa how she’d done it, but all she would say was, “I’ve got a long, skinny arm.”

Lisa Cody disappeared two days later. Somewhere between our ward and the cafeteria she slipped away. Nobody ever found her, though the search went on for more than a week.

“She couldn’t take this place,” said Lisa.

And though we listened for a trace of jealousy in her voice, we didn’t hear one.

Some months later, Lisa ran off again while she was being taken to a gynecology consult at the Mass. General: two days she managed this time. When she got back, she looked especially pleased with herself.

“I saw Lisa Cody,” she said.

“Oooh,” said Georgina. Polly shook her head.

“She’s a real junkie now,” said Lisa, smiling.

Checkmate

We were sitting on the floor in front of the nursing station having a smoke. We liked sitting there. We could keep an eye on the nurses that way.

“On five-minute checks it’s impossible,” said Georgina.

“I did it,” said Lisa Cody.

“Nah,” said the real Lisa. “You didn’t.” She had just started her campaign against Lisa Cody.

“On fifteen, I did it,” Lisa Cody amended.

“Maybe on fifteen,” said Lisa.

“Oh, fifteen’s easy,” said Georgina.

“Wade’s young,” said Lisa. “Fifteen would work.”

I hadn’t tried yet. Although my boyfriend had calmed down about my being in the hospital and come to visit me, the person on checks caught me giving him a blow job, and we’d been put on supervised visits. He wasn’t visiting anymore.

“They caught me,” I said. Everybody knew they’d caught me, but I kept mentioning it because it bothered me.

“Big deal,” said Lisa. “Fuck them.” She laughed. “Fuck

them

and fuck them.”

“I don’t think he could do it in fifteen minutes,” I said.

“No distractions. Right down to business,” said Georgina.

“Who’re you fucking anyhow?” Lisa asked Lisa Cody. Lisa Cody didn’t answer. “You’re not fucking anybody,” said Lisa.

“Fuck you,” said Daisy, who was passing by.

“Hey, Daisy,” said Lisa, “you ever fuck on five-minute checks?”

“I don’t want to fuck these assholes in here,” said Daisy.

“Excuses,” Lisa whispered.

“You’re not fucking anybody either,” said Lisa Cody.

Lisa grinned. “Georgina’s gonna lend me Wade for an afternoon.”

“All it takes is ten minutes,” said Georgina.

“They never caught you?” I asked her.

“They don’t care. They like Wade.”

“You have to fuck patients,” Lisa explained. “Get rid of that stupid boyfriend and get a patient boyfriend.”

“Yeah, that boyfriend sucks,” said Georgina.

“I think he’s cute,” Lisa Cody said.

“He’s trouble,” said Lisa.

I started to sniffle.

Georgina patted me. “He doesn’t even visit,” she pointed out.

“It’s true,” said Lisa. “He’s cute, but he doesn’t visit. And where does he get off with that accent?”

“He’s English. He grew up in Tunisia.” These were very important qualifications for being my boyfriend, I felt.

“Send him back there,” Lisa advised.

“I’ll take him,” said Lisa Cody.

“He can’t fuck in fifteen minutes,” I warned her. “You’d have to give him a blow job.”

“Whatever,” said Lisa Cody.

“I like a blow job now and then,” said Lisa.

Georgina shook her head. “Too salty.”

“I don’t mind that,” I said.

“Did you ever get one that had a really bitter taste, puckery, like lemons, only worse?” Lisa asked.

“Some kind of dick infection,” said Georgina.

“Yuuuch,” said Lisa Cody.

“Nah, it’s not an infection,” said Lisa. “It’s just how some of them taste.”

“Oh, who needs them,” I said.

“We’ll find you a new one in the cafeteria,” said Georgina.

“Bring a few extra back,” said Lisa. She was still restricted to the ward.

“I’m sure Wade knows somebody nice,” Georgina went on.

“Let’s forget it,” I said. The truth was, I didn’t want a crazy boyfriend.

Lisa looked at me. “I know what you’re thinking,” she said. “You don’t want some crazy boyfriend, right?”

I was embarrassed and didn’t say anything.

“You’ll get over it,” she told me. “What choice have you got?”

Everybody laughed. Even I had to laugh.

The person on checks put her head out of the nursing station and bobbed it four times, once for each of us.

“Half-hour checks,” said Georgina. “That would be good.”

“A million dollars would be good, too,” said Lisa Cody.

“This place,” said Lisa.

We all sighed.

Do You Believe Him or Me?

That doctor says he interviewed me for three hours. I say it was twenty minutes. Twenty minutes between my walking in the door and his deciding to send me to McLean. I might have spent another hour in his office while he called the hospital, called my parents, called the taxi. An hour and a half is the most I’ll grant him.

We can’t both be right. Does it matter which of us is right?

It matters to me. But it turns out I’m wrong.

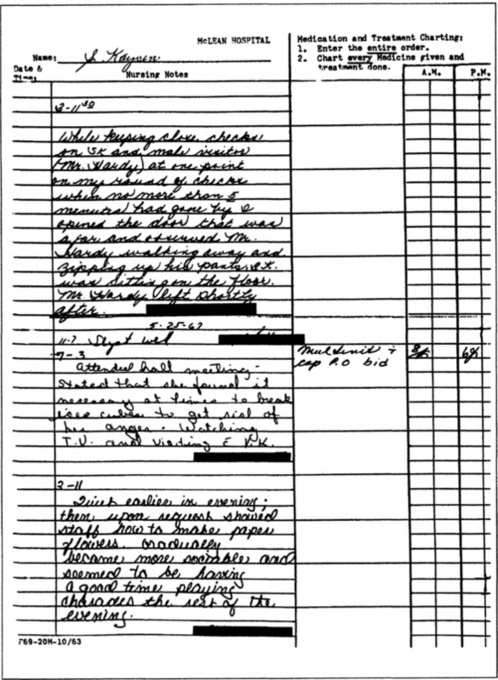

I have a piece of hard evidence, the Time Admitted line from the Nurse’s Report of Patient on Admission. From that I can reconstruct everything. It reads: 1:30

P.M.

I said I left home early. But my idea of early might have been as late as nine in the morning. I’d switched night and day—that was one of the things the doctor harped on.

I said I was in his office before eight, but I seem to have been wrong about that, too.

I’ll compromise by saying that I left home at eight and spent an hour traveling to a nine o’clock appointment. Twenty minutes later is nine-twenty.

Now let’s jump ahead to the taxi ride. The trip from Newton to Belmont takes about half an hour. And I remember waiting fifteen minutes in the Administration Building to sign myself in. Add another fifteen minutes of bureaucracy before I reached the nurse who wrote that report. This totals up to an hour, which means I arrived at the hospital at half past twelve.

And there we are, between nine-twenty and twelve-thirty—a three-hour interview!

I still think I’m right. I’m right about what counts.

But now you believe him.

Don’t be so quick. I have more evidence.

The Admission Note, written by the doctor who supervised my case, and who evidently took an extensive history before I reached that nurse. At the top right corner, at the line Hour of Adm., it reads: 11:30

A.M.

Let’s reconstruct it again.

Subtracting the half hour waiting to be admitted and wading through bureaucracy takes us to eleven o’clock. Subtracting the half-hour taxi ride takes us to ten-thirty. Subtracting the hour I waited while the doctor made phone calls takes us to nine-thirty. Assuming my departure from home at eight o’clock for a nine o’clock appointment results in a half-hour interview.

There we are, between nine and nine-thirty. I won’t quibble over ten minutes.

Now you believe me.

Velocity vs. Viscosity

Insanity comes in two basic varieties: slow and fast.

I’m not talking about onset or duration. I mean the quality of the insanity, the day-to-day business of being nuts.

There are a lot of names: depression, catatonia, mania, anxiety, agitation. They don’t tell you much.

The predominant quality of the slow form is viscosity.

Experience is thick. Perceptions are thickened and dulled Time is slow, dripping slowly through the clogged filter of thickened perception. The body temperature is low. The pulse is sluggish. The immune system is half-asleep. The organism is torpid and brackish. Even the reflexes are diminished, as if the lower leg couldn’t be bothered to jerk itself out of its stupor when the knee is tapped.

Viscosity occurs on a cellular level. And so does velocity.

In contrast to viscosity’s cellular coma, velocity endows every platelet and muscle fiber with a mind of its own, a means of knowing and commenting on its own behavior. There is too much perception, and beyond the plethora of perceptions, a plethora of thoughts about the perceptions and about the fact of having perceptions. Digestion could kill you! What I mean is the unceasing awareness of the processes of digestion could exhaust you to death. And digestion is just an involuntary sideline to thinking, which is where the real trouble begins.

Take a thought—anything; it doesn’t matter. I’m tired of sitting here in front of the nursing station: a perfectly reasonable thought. Here’s what velocity does to it.