Gitchie Girl: The Survivor's Inside Story of the Mass Murders that Shocked the Heartland (2 page)

Read Gitchie Girl: The Survivor's Inside Story of the Mass Murders that Shocked the Heartland Online

Authors: Phil Hamman & Sandy Hamman

Tags: #true crime, mass murder, memoir

At the moment, Vinson was on the police radio calling for a crime-scene photographer. “And get a hold of the Sioux Falls Police Department as well. We’re going to need all the help we can get with this one,” he notified the dispatcher.

The muffled shouts of Deputy Griesse calling his name off in the distance drew Vinson’s attention. The urgency in his deputy’s voice left no doubt that something serious was at hand, yet the sheriff had no idea that the day was about to get considerably worse.

With silky, flowing, brown hair and vivid chestnut-colored eyes, thirteen-year-old Sandra Cheskey had what her friends considered the good fortune of frequently being mistaken for a much older teenager. She was the youngest of four, and her mother, Delores, or Lolo as friends called her, was responsible for both the French and Cheyenne River Sioux genes that contributed to Sandra’s beauty. In her younger days, Lolo had caught the attention of many men herself until Cameron, a young man with good looks and a lean build, came along. Not wanting to lose his prize, Cameron showed up with a ring after just a few months of dating and drove Lolo to the courthouse, where they were married that morning.

Five children followed in quick succession, but her second, a baby boy, died shortly after birth. The doting nun at the small Catholic hospital showed the baby to Lolo before quickly scurrying the lifeless bundle out of the room. Exhausted and shocked from losing her newborn, it didn’t occur to Lolo at the time to ask to hold her baby, and the anguish she felt from that decision followed her for the rest of her life. At the time, she could not imagine a worse pain for a mother.

Soon, two more boys followed, and when Lolo went into labor with Sandra, she nearly lost her, too. Lolo was staying with relatives in the remote town of Eagle Butte, South Dakota, when the contractions came suddenly. As luck would have it, the only person around was a neighbor with little driving experience. While the neighbor lady careened down isolated roads to the nearest hospital, Lolo gritted her teeth and clenched the seat to suppress screams of pain, fearing she’d distract the lady and cause her to drive off the road. That wasn’t the biggest problem, however. Having delivered four previous babies, her labor progressed quickly, and Sandra made her entrance in the back seat of the car. The inexperienced driver was so focused on the road that she didn’t realize Lolo had given birth until Sandra announced her arrival with the screams of a healthy baby. Perhaps this unusual birth foreshadowed a life that would be equally remarkable.

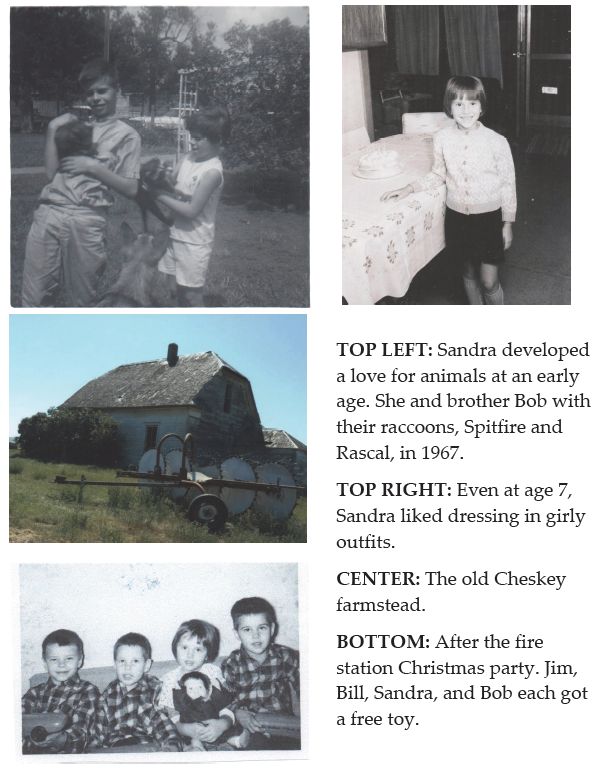

As the years went by, financial stress along with the strain of raising four children led to more frequent bickering between Lolo and Cameron. The marriage didn’t last, and Lolo eventually found herself with three rambunctious boys and one little girl who adored her older brothers, Bob, Jim, and Bill. Four of them vying for their mother’s limited time left Sandra craving for attention Lolo couldn’t always provide. In addition to working long hours, Lolo had returned to school to become a nurse. So it was decided that it would be best for everyone if the children went to live with their Cheskey grandparents for a time. The children would end up staying there from the time Sandra was eighteen months old until she was almost four. She and her brothers loved this farmstead with the cracked and weathered white paint peeling from the house and a slumping old barn where Sandra and her brothers played, made up games, and developed a love for animals.

It wasn’t easy for these aging grandparents to care for the children on a farm where the only modern convenience was electricity, as there was no telephone or running water, but they did it without ever complaining. On Sundays the children awoke to the sweet aroma of homemade cinnamon rolls that Grandma baked before sunrise. Sandra would watch the slice of butter slowly melt down the edges of the soft roll before breaking off small pieces of the warm pastry and enjoying every bite of the fluffy treat which she washed down with a glass of fresh, cold milk.

On weekdays, Grandma washed clothes in a wringer washer, and Sandra would hand her wooden clothespins when it was time to hang them on the line. Every morning she braided Sandra’s hair, insisting the little girl look neat and presentable, then made everyone a hot breakfast of cinnamon-sugar toast and oatmeal. The boys helped with small chores, and all of them spent as much time as they could outdoors.

Her grandpa would often lift Sandra onto his lap whenever there was work to be done using the faded green John Deere tractor. He was grateful for the company after so much solitary farm work, and Grandma was grateful for the break from chasing a preschooler. Grandpa would fire up the old beast of a tractor until it chugged to life and lurched them forward with puffs of black smoke billowing from the vertical exhaust pipe. She would wait on the metal seat while he filled the tractor next to a big gas tank in the yard.

“There won’t be a single cow escaping once we’re done checking this fence,” he said as they bounced along, stopping occasionally to fix a wooden post or a stretch of rusty barbed-wire.

Sandra, who jumped from bed every morning and ran to the window to get a glimpse of the farm animals she considered her “pets,” worried that one of the placid cows might end up lost or hurt. Her grandparents marveled at her awareness of animals at such a young age.

“When I’m big I’ll bring all the hurt animals here. I’ll put them in the barn. I’ll make them all better.”

Grandpa nodded.

Sandra was brought up attending a Christian church, but with her Native bloodlines she was also raised to respect the circle of life and the great power that keeps the entire universe in balance. The call to do good and believe in good things was a constant presence in her family. At the table, they always sat with folded hands before the meal was served. “Dear God, we pray for those who are homeless and for the well-being of those who are sick or weak. We ask for the wisdom to care for these animals in our charge and for the protection of us all.”

And for all the animals everywhere

, she thought, knowing that someday she would bring all the hurt animals she could find to this place of peace and beauty.

Grandpa didn’t have any hobbies or spend any time relaxing except for late in the evening. He collapsed in his favorite chair each night, and Sandra would climb up on his lap. She wasn’t aware of the aged changes occurring in his body since he performed the difficult farm work without complaint. “Sandra, did you save any animals today?” He was truly interested and not just indulging her childhood obsession.

She nodded seriously. “Three worms and one grasshopper. They were lost in the grass so I put them in the garden by a big flower.”

“You’re a kind girl. God did good with you.”

He was right. Even when she wasn’t completely good, she was never too naughty. She’d never even been spanked. She occasionally took advantage of being not only the youngest but the only girl as well. Especially on bath night. Grandma would fill a big galvanized tub with hot water from the stove. The tub was in the kitchen, the warmest spot, and Sandra got the first bath. She would take her time sudsing and playing until Grandma would finally pick her up out of the tub in exasperation. Each brother to follow was left with colder and dirtier water than the one before. Then snug in her pajamas, Sandra would take off in search of Grandpa, who would of course be in his chair, and crawl onto his lap.

The happy, hard-working life continued without a problem except that the children rarely got to see Lolo. They were up at dawn, had become proficient in their little chores, had plenty to eat, and plenty of love to go around, which allowed them to focus on what they did have rather than what they didn’t have, which was also plenty. Before Sandra turned four, she and her brothers were able to rejoin Lolo in a nearby town, and a few months later, Grandma sent word that Grandpa had died in his sleep, sitting up in his favorite chair.

The four children spent hours together entertaining themselves since Lolo had earned a two-year nursing degree and worked long hours before returning home to an evening of keeping up a household. She didn’t earn nearly as much as a registered nurse and with four kids and loans to pay the family qualified for some government assistance. Each month Lolo would pile the kids into the car, and they’d go together to pick up a box of commodities, usually containing things they loved like cheese and peanut butter. She could have picked up the food on her way home but wanted them to know where it came from.

“I’m so grateful for this food,” she’d remind them each month. This focus on thankfulness would stick with Sandra and be a key to helping her deal with future struggles. There were few complaints from Lolo no matter what life threw her way. She didn’t judge people, she tried to understand them, and all her children absorbed this philosophy.

At Christmas Lolo made a trip to the local fire station with the four kids in tow bundled in their winter wear, clean but a little too snug. The air was buzzing with childhood expectations as they waited excitedly in line to receive a present. “Merry Christmas!” a spirited fireman eagerly greeted them before handing Sandra a doll and each of her brothers a truck. Though amazed by the gifts, none of them needed prompting to say thank you, which gave Lolo warm satisfaction. When they got home, one of the boys hurried the others into a bedroom and shut the door. “We don’t have anything for Mom. She’s not going to get a single present!” So they huddled together on the floor around a piece of paper and made her a card. That night the family passed the time singing Christmas carols, eating hot tuna casserole, and reflecting on the excitement of getting these unexpected gifts. While the boys whooped and hollered around her, Sandra escaped to a quiet corner with her new doll, where she spent the night playing nurse and fixing her doll’s imaginary broken bones with toothpick splints she’d taped onto the legs.

With Lolo working long hours, the children took on responsibilities at an earlier age than most of their peers and learned to depend on each other. Wherever Bill was, Sandra was close behind. The kids were unaware of their dearth of material possessions so this had no effect on their happiness. Her brothers were boys to the core and proficient at their mischief, frequently harassing Sandra with various pranks. One night she went into her bedroom and reached for the dangling pull string to turn on the overhead light. Instead of the pull string she felt something squishy and hairy in her grasp and let loose a marathon of shrill screams. Lolo screamed as loud as Sandra, but it was directed at the boys when she found out they had tied a dead mouse to the light cord.

Family was so important that the strong bonds between Grandma Cheskey and her grandchildren sustained time and distance. When Sandra and her brothers returned for a visit, they took to the farm as if they’d never left it. The farm had remained untouched by most modern conveniences. It still lacked indoor plumbing, and the children quickly adapted to making the jaunt out to the weathered-wood outhouse with its stacks of Sears catalogs perched on the bench seat next to the obligatory hole. It was too dark and cold to stumble out there at night, so Grandma gave each of them a large juice can to use instead. In the mornings, they were responsible for dumping the contents of the can into the hole in the outhouse, which Sandra would do immediately upon rising. Her brothers weren’t as consistent though, and Grandma would regularly find an undumped can in a bedroom upstairs.

“It’s not mine!” her brothers would all claim, and with Sandra being the youngest, Grandma always believed the boys and assumed her little granddaughter had simply forgotten. Out she’d walk holding one of her brothers’ cans with her arms stretched out in front of her as far as she could and pouting all the way while they tried to silence their teasing laughter. They loved Sandra, but she quickly learned how to match their playful scheming. The farm left Sandra with memories of love that would empower her in times of hopelessness.

1971-1972

By the time Sandra started school, Lolo had found a new man to share her life. As the years went by with all of them under one roof, the stress of four children began to cause problems. Sandra’s brother Bill, longing for the independence typical of someone on the cusp of teenhood, especially despised this new man in their lives. “You’re not our dad, you son of a bitch! I hate you!” he would scream. The fighting became a daily ritual that upset Sandra deeply even though this new man mostly ignored her.

Years of friction came to a head one day when Sandra arrived home to find that she and Bill were being sent to live with separate foster families. She was confused. A relative said it was because the kids were not minding the adults and that there was underage drinking. Sandra hadn’t been drinking, and she wasn’t a discipline problem. The only thing she could think of was this new man was not able to deal with all of the children.

Sandra was whisked into the home of a foster family. But not for long. She sobbed into the phone recounting for Lolo how the foster parents had severely beaten their own child with a wire coat hanger. Lolo made arrangements for Sandra to be removed. It was a short-lived relief. Within days Sandra arrived at the doorstep of a second foster family yet held her head high, supported by the empowering words of her father, “You’re going to be my little Miss America someday!” It was one of the few memories she retained of him. But the distant words turned powerless in the hands of this cold, uncaring foster family. The family members rarely talked to or even acknowledged her. She felt more like an unpaid hired hand than a child.