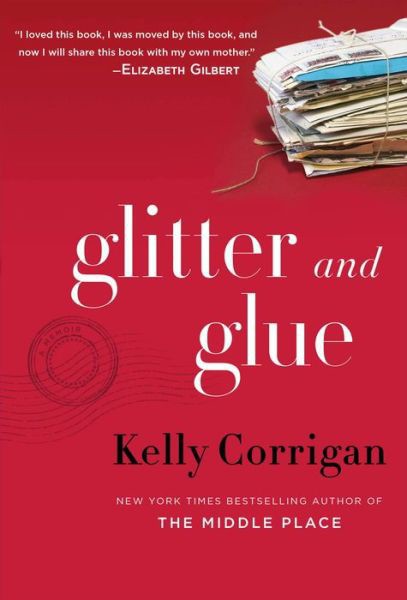

Glitter and Glue

Authors: Kelly Corrigan

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Nonfiction, #Personal Memoir, #Retail

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details of people described in this book have been changed to protect their privacy.

Copyright © 2014 by Kelly Corrigan

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

B

ALLANTINE

and the H

OUSE

colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Corrigan, Kelly.

Glitter and glue : a memoir / Kelly Corrigan.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-345-53283-1

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-53284-8

1. Corrigan, Kelly, 1967–. 2. Corrigan, Kelly, 1967– —Family.

3. Mothers and daughters. 4. Motherhood. 5. Young women—United States—Biography. 6. Corrigan, Kelly, 1967– —Travel—Australia—Sydney. 7. Americans—Australia—Sydney

(N.S.W.)—Biography. 8. Young women—Australia—Sydney

(N.S.W.)—Biography. 9. Nannies—Australia—Sydney (N.S.W.)—

Biography. 10. Sydney (N.S.W.)—Biography. I. Title.

CT275.C7875A3 2014

994.4092—dc23 [B] 2013041936

Jacket design: Misa Erder

Jacket photo: © Ekely / Getty Images

v3.1

UTHOR

’

S

N

OTE

This is a work of memory, and mine is as flawed and biased as any other. I was aided by dozens of old letters, photographs, journals (both mine and my friend Tracy’s), and the Internet, on which I could call up images of just about everywhere I went in 1992. Many of the names and personal details have been changed.

Prologue

PrologueWhen I was growing up, my mom was guided by the strong belief that to befriend me was to deny me the one thing a kid really needed to survive childhood: a mother. Consequently, we were never one of those Mommy & Me pairs who sat close or giggled. She didn’t wink at me or gush about how pretty I looked or rub my back to help me fall asleep. She was not a big fan of deep conversation, and she still doesn’t go for a lot of physical contact. She looked at motherhood less as a joy to be relished than as a job to be done, serious work with serious repercussions, and I left childhood assuming our way of being with each other, adversarial but functional, was as it would be.

If my mother thought of me as someone to guide, my father thought of me as someone to cheer. I was his girl, as in

That’s my girl! Have you met my girl?

He liked to hold hands and high-five and was almost impossible to frustrate or disappoint. His signature

You bet! Why not?

energy was all I needed for several decades. But then my daily life became more consequential, and I woke up needing things he could not supply—a certain understanding, call it a seasoning—that only my mother seemed to have. Her areas of expertise, which often had appeared piddling or immaterial, became disturbingly relevant. And that’s saying

nothing about the second-guessing and anxieties I could take to her, worries that would only ever bounce off my dad’s optimism, as was the case on the day I was told I needed surgery.

I remember leaving the doctor thinking three things:

I can’t have more kids

.

It’s for my own good

.

I need my mom

.

On the way to the parking lot, I dialed home or, I should say, the place that was home when I was a child. My dad ran to pick up the phone on the first ring. I know because I’ve seen him do it a hundred times. He loves connecting, he’s dying to catch up, can’t wait to hear your voice, anyone’s voice.

“Lovey!” he sang out, as if it had been years, not days, since we talked. “How’s my girl?”

“I’m okay. Is Mom there?” I wasn’t crying, but I wanted to.

“What?” he said in mock hysteria. “You don’t want to talk to Greenie? The Green Man?” My dad’s brothers have been calling him Greenie since college. I always thought it referred to the Irish in him, but it turns out it’s more about a bad hangover. “You’re breaking my heart, Lovey!”

“Sorry. I just need Mom.”

“She’s at the bridge table, probably making her opponents weep right this minute!”

I asked him to have her call me when she got back, and told him I couldn’t talk right now. That was A-OK with him, because everything is A-OK with him.

“Love ya, mean it,” he signed off, as usual.

“Love ya, mean it.”

Before I got in my car, I called my mom’s cell and left a message explaining that Dr. Rawson would be taking out my ovaries a week from Thursday. I tried to sound cool and relaxed

about it. I said I was being spayed, ha ha. I hoped she would hear past my witty BS.

Two years before, a lump I found in my breast turned out to be a seven-centimeter tumor. So I did what people with tumors do: chemotherapy, radiation, surgery. I also started taking a tiny pill every day to suppress ovarian function, since my cancer used estrogen to multiply. After ninety days, my periods kept coming. I bragged to the doc that I was born to breed. Turned out there was something on my ovary—a cyst, most likely—but it did not wax and wane, the way cysts should. It sat there, stubborn and ominous. The time had come.

“You have kids?” the doctor asked.

“Yeah, two girls. Three and five.”

“We do this now, and maybe we avoid something worse later.”

Crossing the Bay Bridge, San Francisco disappearing behind me, I did not call my husband. Edward was a reasonable man who took zinc at the first sign of a cold, stretched thoroughly before and after exercise, and, when lifting heavy objects, used his legs, not his back. He was, in all situations, an advocate for avoiding something worse.

I did not call either of my older brothers, I do not have a sister, and I was not quite ready to involve a girlfriend. So I called my mom’s cell again, and this time she answered. She said she’d just hung up with

the idiot at the airlines

who wouldn’t accept her frequent-flier miles, which were

barely

expired, and I said, “God help the customer service guy who took that call,” but what I thought was

She’s coming

.

She arrived from Philly the day before I went in for surgery, letting Edward carry her tiny black suitcase on wheels up the stairs, where she would unpack all her must-haves: a silk pillowcase

that keeps her hairdo looking nice, her mauve bathrobe with giant pearly buttons, a small jelly jar of Smirnoff because she doesn’t like the expensive vodka we buy, and several strange secondhand presents—a bedazzled purse, one of my old Nancy Drews, a down vest with a broken zipper—for the girls. Georgia and Claire love her and always have. She’s different with them. She makes Jell-O—

a hundred percent sugar-free, Kelly

—and plays Crazy Eights and rubs lotion on their clean feet and reads them whatever they bring to her, even the long books with no pictures. When she leaves them, she cries. Actually cries, with real tears. From a woman who extended the adage

Children should be seen and not heard

with

and preferably not seen

, it’s startling, like opening your toolbox and discovering that your supposedly industrial-strength staples are made of Play-Doh.

After the procedure, Edward brought me home, where everything was fine and good and just the same but somehow different. The girls gave me homemade cards with words my mom helped them spell, like

operation

and

recovery

. I showed them my bandage. Then Edward said, “All right, ladies, the day is done. Up we go.”

The next morning, Edward dropped the girls at school on the way to work while I lay in bed and listened to my mom talk on the phone to my dad. “Make sure to check the leak in the basement … and call the dry cleaners and tell them they overcharged us … She’s doing well … the girls are divine … All right, will do.”

I was in bed, not wanting to ask her to come sit with me but still listening for her footsteps on the stairs.

After a while, she called up, “Need anything from Florence Nightingale?”

“The newspaper, or some company, maybe.”

She grabbed the railing and made her way up to me.

We talked about my new comforter cover, how I got it on sale because of one tiny tear.

Good for you

.

I told her a story about Claire not wanting to get older because then she would have to move out and live far away.

That Claire

.

She swore she was going to quit selling real estate one of these days.

My God, it’s been twenty years

.

We rolled our eyes about my dad and how he plans his life around the Radnor High School lacrosse schedule and then acknowledged how good the kids from the team have been, coming to clean the gutters in the fall and shovel the driveway after it snows.

Anything for Coach Corrigan

.

I asked her when I should look at my scars, and she said,

Never

. She said she hasn’t looked at her naked stomach since the sixties, when it was still flat and unstretched.

We kept up the chitchat, never breaking the rhythm of our conversational song because it had been a long two years of thinking hard thoughts, and my mom doesn’t like that crap.

“Well, I’m gonna let you sleep,” she decided, pulling the string that dropped my shade and muttering about the pulley and how she can never get the

damn thing

to release.