Glorious

Authors: Jeff Guinn

A

LSO

BY

J

EFF

G

UINN

Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson

The Last Gunfight: The Real Story of the Shootout at the O.K. CorralâAnd How It Changed the American West

Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA ⢠Canada ⢠UK ⢠Ireland ⢠Australia ⢠New Zealand ⢠India ⢠South Africa ⢠China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by 24 Words, LLC

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Guinn, Jeff.

Glorious / Jeff Guinn.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-101-62321-3

1. Fortune huntersâFiction. 2. Gold mines and miningâFiction. I. Title.

PS3557.U375G57 2014 2013037961

813'.54âdc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For Ivan Held

Â

Â

Â

Â

LORIOUS

1872

They took Tom Gaumer late in the morning.

He shouldn't have been out alone. Like all the other prospectors in Glorious, Gaumer knew the area was crawling with Apaches. You didn't have to see them to know that they were there. In the three weeks since he'd arrived in the tiny town, Gaumer went out on his daily hunt for silver with four other prospectors, all of them frontier veterans who observed the proper precautions: stay together, make as little noise as possible, take turns acting as lookout. The Indians generally didn't bother well-armed men working in groups. They wanted easier white prey.

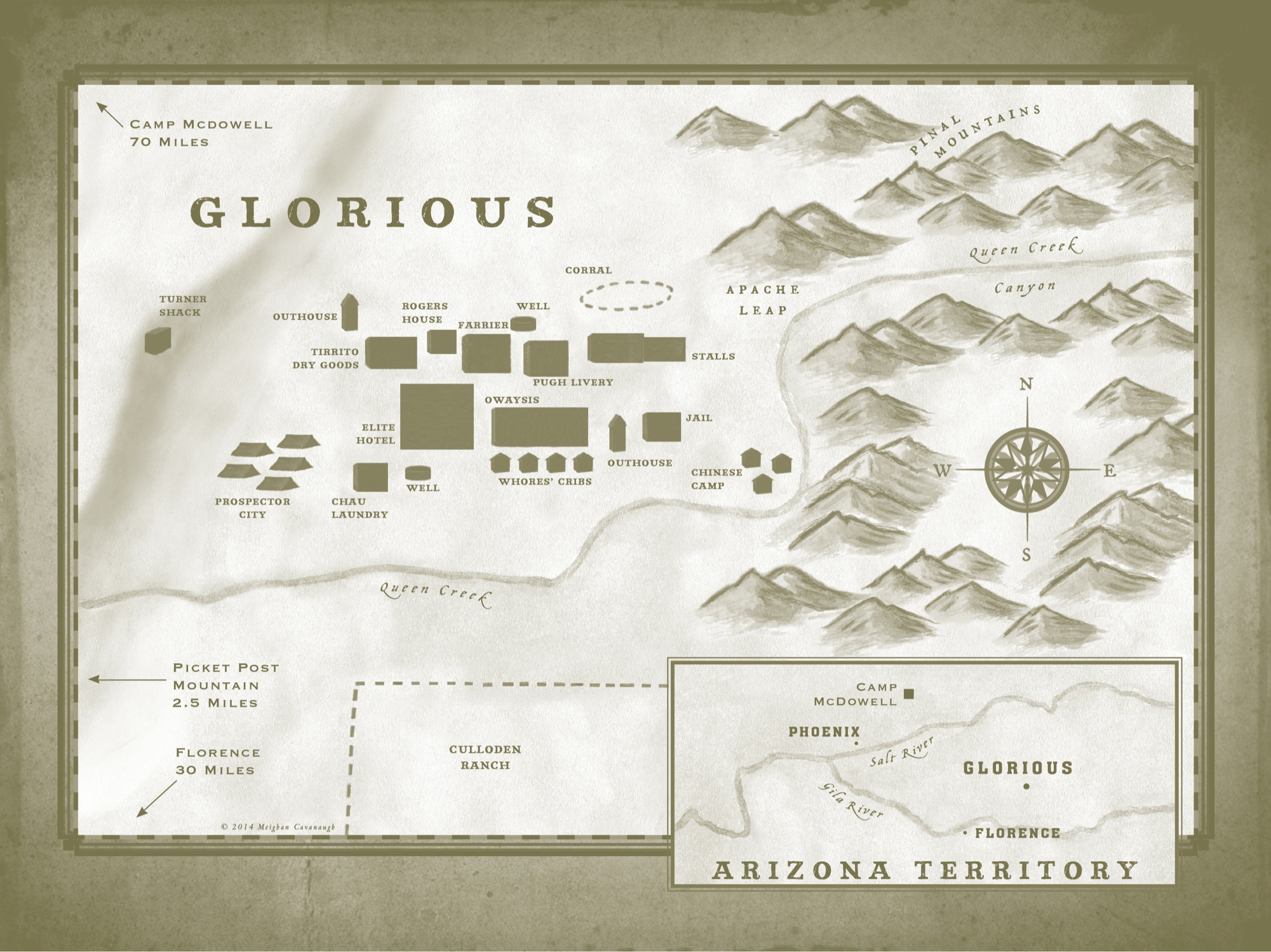

But the day before, Gaumer had noticed a particularly promising bit of oxidized, black-lined rock, typical of potentially significant silver content. He and his informal partnersâthey'd all met on arrival in Gloriousâwere working about three miles northeast of town along the banks of Queen Creek, in an area where the creek cut around the base of the Pinal Mountains. Bossman Wright was on lookout, and Oafie and Archie and Old Ben and Gaumer were chipping away on a ledge, each no more than ten yards from the others because the Apache could snatch anyone

straying too far in an eye blink. When Gaumer's pick dislodged the first black-lined rock chunks he drew breath to holler out the news to the others, and then thought better of it. None of the others were turning up anything interesting; that was the way of even the widest silver seams, to have surface concentration in one small spot, and it was his luck alone to find it. These men he'd been working with were fine fellows, but Gaumer had a wife and two daughters back in Minnesota who lived in near poverty while he was away trying to strike it rich for them. So Gaumer took a good look to mark the exact place in his mind, then casually said, “Nothing's here. Let's try farther downriver.” Much to his relief, the others muttered agreement and moved on.

The next morning in the prospectors' tent city just beyond the few permanent buildings in Glorious, Gaumer told the other four to go on without him, he had stomach trouble and would rest all day. He lay in his blankets until everyone in the prospectors' camp was gone, all of them disappearing into the vastness surrounding Glorious. Then Gaumer jumped up and started back toward his secret treasure spot, keeping a sharp eye out for anyone who might be exploring the same general area. But his luck held. By the time he was back on the ledge he felt certain that he was miles away from anyone else. It was risky to be out alone, but Gaumer didn't care. In all his years of prospecting, he'd never seen such strong silver sign. He soon lost himself chipping away at the black-lined rock, the lines getting tantalizingly thicker and more numerous: my God, there was going to be a fortune in silver here! He'd done it! This was it! As he was exulting, they came quietly up behind him. A rope snared Gaumer's arms to his sides and just like that he was helpless.

They took their time with the torture and mutilation. First they built a fire and used the brands to burn the soles of Gaumer's feet. He screamed, but his screams were lost in the cliffs and canyons. They amused themselves for a while removing Gaumer's fingers one joint at a

time, and then there was some skinning, parts of his chest and back. By then he was periodically passing out from the pain, coming to when they briefly stopped, shrieking when they resumed until the agony was too overwhelming and blessed blackness descended on him again.

His captors knew their business. It was almost nightfall when Gaumer finally succumbed. His last sensation was of fresh pain. One of them was dragging a sharp knife along the hairline of his forehead. Gaumer only spoke English, not their language, but he'd been in Arizona Territory long enough to comprehend meaning if not individual words. Gaumer thought one of them was saying, “StopâApaches don't scalp.”

Then the final darkness swallowed

him.

NE

S

hortly before the morning stage left Florence for the thirty-mile trip to Glorious, Mr. Billings, the depot manager, took Cash McLendon aside.

“I hope you've taken advantage of our privy, sir,” Mr. Billings said. “Passage to Glorious is wearying at best. You'll want to avoid additional discomfort.”

The suggestion surprised McLendon, who replied, “I'm not concerned. Today's is only a short trip, every depot along the way will have facilities, and in between scheduled stops I can always tap on the stage roof and signal the driver to pull over.”

Mr. Billings, a square-shaped man with muttonchop whiskers, shook his head. “I see from your ticket that you've come to us all the way from Texas. Up to now, you've followed mostly well-established routes on decent roads. But the way to Glorious is rough travel, very hard going, and there are no depots along the way. You'll not find another privy between here and there.”

McLendon was bone-weary from riding inside cramped

stagecoaches during the three weeks it had taken him to get from Galveston to Florence in Arizona Territory, and he was further discomfited by the memory of why he'd fled St. Louis nearly two months before that. Throughout much of this wretched time, he sustained himself with the belief that if he could only get to Glorious, everything might yet be all right. All he knew about the place was its name, but that was enough. He wanted to board one last stagecoach and find out what was going to happen, one way or the other.

“Even with no depots, the matter of a comfort stop seems simple enough,” McLendon said, hoping to convey through a friendly but firm tone that the subject was closed. “I'll bang on the roof and the driver will accommodate me.” But Mr. Billings shook his head again.

“We leave the matter of such pauses to the driver's discretion, and of course you can signal him all you like,” the depot manager said. “But on this route it's unlikely he'll rein in on passenger request, and even if he would, as a sensible man you'd not want to step down from the stage and remove yourself even a short distance to take your stance or squat. That's due to the Apaches, of course. They're always alert to pick off any white man who foolishly separates himself from his companions.”

“I suspect that you exaggerate,” McLendon said. “I saw no sign of Apache on the journey here from Tucson, and it's my understanding that most of them ride with Cochise well away to the south and east.”

“Please observe the sign,” Mr. Billings said, and pointed to a large poster by the depot door. In all capital letters it warned:

YOU WILL BE TRAVELING THROUGH

INDIAN COUNTRY AND THE SAFETY

OF YOUR PERSON CANNOT BE

VOUCHSAFED BY ANYONE BUT GOD!

“Those are the truest of words,” Mr. Billings said. “You have no idea of how dangerous this country is. I assure you that these savages lurk behind every rock and bit of brush between here and Glorious, and the thing about Apaches is that you don't see them until they're upon you. The savages got a prospector just outside of Glorious not two weeks ago, and they butchered him up like a hog. Trust me on this, sir. If you require additional testimony, inquire of your driver or anyone else with some experience in this region. Make use of the privy here, and then remain alert all the way to Glorious, where I doubt you'll want to linger very long.”

McLendon reminded himself that the man was trying to be helpful. “And why is that, sir?”

“Why, there's nothing to the place,” Mr. Billings said. “Don't let the braggardly name deceive you. A few buildings and some prospectors' tents is all of it. We run this stage once a week because you never know what may happen with these meager little towns. Most vanish right off the map in a matter of months when no significant lodes of ore are discovered. But on those rare occasions when a major strike is made, why, it seems that everyone on earth immediately wants to hurry to the spot, so we have a Glorious route in place just in case. Meaning no disrespect, you seem to me more likely a businessman than a prospector, and someone accustomed to a degree of comfort. There's none of that in Glorious, I assure you.” Mr. Billings paused, waiting for McLendon to mention his reason for such an unlikely destination. When he didn't, the depot manager continued: “Well, then, I'll inform you that the stage and driver will remain in Glorious overnight and return here tomorrow. After that, it's another week before our next stage arrives. Should you decide to come back in the morning and spare yourself such a long delay, the fare is three dollars, the same as you're paying to make the Glorious trip today. Just give

the money to the driver, as we have no formal depot there. And now I thank you for your business, and wish you the best day possible under the circumstances in which you'll presently find yourself.”

McLendon waited until Mr. Billings disappeared inside the chinked wood depot before hustling to the rank privy behind the building. Even though the ride to Glorious surely wouldn't take too longâit was only some thirty miles, and McLendon knew that stages routinely covered ninety or a hundred miles in a dayâit was disturbing to learn that there would probably be no relief stops along the way. His digestive system was in a disrupted condition brought on by the meals he'd consumed since Galveston. Depot food was expensive, sometimes as much as a dollar a plateâtwice the price of a meal at a decent hotelâand the fare was almost always limited to bacon, beans, biscuits, and foul-tasting coffee or tea, with the occasional substitution of tough, stringy beef or salty sowbelly as the main course. Because depot stops were usually limited to twenty minutes while fresh teams of horses were hitched to the stage, there was never time to wander off in search of more palatable meals. McLendon couldn't remember the last time he'd eaten a vegetable other than the ubiquitous mushy depot beans. In recent days, the constipation he had endured since the beginning of the trip from Texas was replaced by periodic piercing urges to evacuate that struck without warning. As he closed himself inside the fly-infested outhouse, he reflected that for the moment, at least, he feared the Apache far less than he did ruining his remaining pair of relatively clean trousers.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

A

FTER

M

C

L

ENDON

finished his business in the privy, he went back inside the depot and collected his valise. When he'd fled St. Louis, the bag was shiny and redolent of expensive leather. Now it was

gashed in several places, and the handle was held in place with twine. Stage travel was hard on luggage. Each passenger was allowed twenty-five pounds of baggage, but McLendon's battered valise was considerably lighter. It contained only a book, the sheet music for “Shoo Fly, Don't Bother Me,” four shirts, some drawers, the denim jeans he'd purchased in New Orleans while working on the docks there, a few pairs of socks, some toiletries, and the suit he was saving to wear when he surprised Gabrielle in Glorious. It was an expensive suit, hand-tailored to fit his slender frame, and McLendon hoped the prosperous appearance wearing the suit gave him wouldn't be offset by any stench acquired from the long-unwashed clothes packed around it. The valise also contained the .36 caliber Navy Colt he bought in Houston after observing that all of the passengers on the westbound stage were armed, including the women, and a box of cartridges he'd purchased at the same time. One handgun was the same as the next to McLendon, who'd never owned or even fired one before. The shop owner assured him that the Navy Colt was popular among frontier travelers, and particularly excellent protection for a beginner marksmanâ“Just cock, point, and pull the trigger.” For the first few days McLendon concealed the weapon in his coat pocket, but the sagging weight of it was distracting and he decided to carry it in his bag instead. Since he rode with the valise crammed behind his legs underneath the stagecoach bench, he could get to the gun quickly if the need ever arose, which fortunately it so far hadn't. McLendon's remaining money, a roll of about eight hundred dollars in greenbacks and a few gold double eagles, was kept in his trousers pocket. He'd left St. Louis in February with nearly two thousand dollars, and now it was May; life on the run was proving expensive.

McLendon carried his valise over to the Glorious stage, which was being loaded by a depot crew. The appearance of the vehicle gave him

pause. Until now, the stages he had ridden to Arizona Territory from Texas had been stout, impressive conveyances, with wide wheels and sturdy carriages and varnished sides that glistened in the sun. Their appearances had given a sense of reliability. But this one looked rickety in the extreme. The driver's bench sagged on one side, and the sides of the carriage were so stained with streaked dirt and dried clots of mud that it was impossible to tell what shade of paint or varnish might lie beneath. McLendon feared that the thing might collapse entirely the moment he stepped aboard, but apparently the fragile-looking vehicle was able to support modest loads. During previous stops on his long journey, he'd seen stages laden with mailbags, but this time there was only a small mail pouch. The citizens of Glorious didn't receive many letters. The stage roof and boot were being packed with wooden crates. According to labels, these contained mostly canned foodâpeaches, pears, and tomatoes. He saw several marked

SUGAR

and

COFFEE

, while a large crate was mysteriously labeled

MISCELLANEOUS

. Next to the stage, two wagons were hitched together, and these, too, were being loaded with crates of canned goods. The depot workers also hoisted bulky wooden casks onto one of the wagons. From the sounds of sloshing liquid, McLendon guessed they held whiskey or beer, probably both. Perhaps Glorious had a saloon. He already knew there was a store in town, because Gabrielle and her father, Salvatore, ran it.

The clopping of heavy hooves caught McLendon's attention. Four Army cavalrymen pulled up alongside the stage and wagons. McLendon knew as little about horses as he did about handguns, but even he could tell that the soldiers' mounts were the next thing to brokendown. Their coats were dull with age as well as dust, and when their riders dismounted the horses hung their heads listlessly. The cavalrymen were equally unimpressive. Their uniforms were patched and

filthy; one appeared to be drunk. Another of the raggedy soldiers exchanged friendly greetings with the grizzled fellow who was apparently going to drive McLendon's stage. “An Army wagon is taking supplies and messages from Camp McDowell to Camp Grant, which is southeast of Glorious,” a worker loading cases told McLendon. “As a courtesy to civilian stage operations, the Camp McDowell commander is sending his wagon and some cavalrymen partway with your stage as an escort.”

“Can those sad creatures they're riding keep up with the stage?” McLendon asked. “I doubt that they can even trot a little, let alone gallop.”

“Sorry as they are, they'll keep the pace with this team,” the worker said, and gestured to the depot corral, where four rawboned braying mules were being forced into harness. “There's little opportunity for galloping or trotting on the way to Glorious. The trail's too rough. Your typical team of horses would all go lame. Mules, though, can pick their way forward. It's travel slow but sure.”

“How slow?” McLendon asked. “It's still early morning, and with a trip of just thirty miles I thought that we'd easily reach Glorious by noon.”

“A bit before dark is more likely, and that's if the stage or one of the wagons don't throw a wheel,” the man said. “You best get some food for along the way.” McLendon had hoped for a more appealing meal when he reached Glorious, but the worker seemed positive that the trip would take all day. So McLendon bought food from Mr. Billings, tossed his valise up through the open stage door, and clambered inside the carriage. There were only two benches there instead of three; the stages from Galveston to Tucson all seated nine, three to a bench, with facing passengers interlocking knees because of limited space. In several instances there were too many passengers to squeeze

onto the benches, so the overflow perched atop baggage tied to the roof or else wedged themselves on the outside bench between the driver and shotgun guard. But besides McLendon, the morning stage to Glorious had only one additional passenger, a tall red-faced fellow in a checked suit who nodded companionably as he sat down on the opposite bench and stowed his own case underneath. The stage rocked as the driver and shotgun guard climbed up to their outside seats. McLendon pushed the cloth window curtain aside and stuck his head out to watch as drivers took the reins of the two wagons, which were also pulled by teams of mules. The four cavalrymen nudged their horses up, two ahead and two behind the three-vehicle convoy. The stage lurched slowly forward with the wagons directly behind. McLendon expected the stage driver to quicken the mules' pace as soon as they were clear of the Florence depot, but he didn't. The convoy headed slowly east and a little north; McLendon was certain that if he jumped out and walked, he'd be faster than the mules.

For all Mr. Billings's dire warnings about rough terrain, the going seemed easy enough. There was very little to look at as the stage crept along except sandy flats speckled with scrubby cactus and brush. It was going to be a long, tedious trip, and McLendon sighed as he pulled his head back inside and tried to settle himself with some minimal degree of comfort on the thinly padded seat. Enjoying elbow room for a change, he pulled a battered book from his bag: James Fenimore Cooper's

Last of the Mohicans

. McLendon loved the story's vivid descriptions of valorous acts and appreciated its unhappy ending, which struck him as truer to real life than a triumphant climax. He'd read the book so often that he had memorized many passages. In recent months, with everything else in his life so desperate and changed, he'd drawn comfort from the familiarity. Now, nerves on edge since his arrival in Glorious was finally imminent, McLendon

tried to distract himself again with the exploits of Hawkeye, Uncas, and Chingachgook, but it proved impossible. Even on fairly level ground the stage bumped along, and without being braced on his bench by other passengers McLendon found his head and shoulders bouncing painfully off the cab doors and roof. He sighed and tucked the book back in his valise.