gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (58 page)

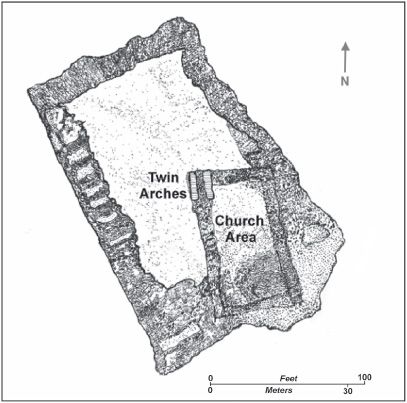

Figure 39.2. Plan of Dera Sor, the ruins of the Yeghrdut monastery, drawn by the author following his return from the site in September 2012. Note the different alignment of the building structure contained within the southeast quadrant of the perimeter wall, suggesting that it might belong to a different age.

The identity of the ruins attached to the twin arches has been impossible to establish with any degree of certainty, as no surviving photographs or plans of the monastery have been found.

12

Present somewhere in the monastery’s southeast quadrant was a large, domed church dedicated to the Mother of God. Attached to it was a chapel of Saint John the Baptist in which was a martyrium where the saint’s relics were kept. Here too was another chapel dedicated to Gregory the Illuminator, located beyond the church’s northwest corner. Its position was marked by an imposing bell tower, under which was a walkway into the main church, the walls of which were constructed of stone in three different colors—black, yellow, and reddish brown. Apparently, the bell tower collapsed during an earthquake in 1866, a portent perhaps of the imminent destruction of the monastery and the disappearance of its monks at the time of the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Exactly what happened here at Yeghrdut may never be known, but it is unlikely to have been pleasant, and as for the fate of the monastery’s precious relics, no one can say. Those Armenians who remain today in Mush have adopted a radical form of Islam, so it is unlikely that any real answers will be forthcoming any time soon.

I was pretty sure that the bell tower was located somewhere in the vicinity of the stone arches; indeed, they might easily have formed its support columns, under which one passed to enter the main church. In my dream the monks had conducted the strange ritual involving the elevation of the fragment of the Tree of Life at the center of the church. So I now stood the closest I was going to get to that very spot, which was a strange sensation, especially after traveling nearly 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) to be there.

SPECTACULAR VIEWS

As I moved across to the piles of debris marking the north wall, I realized just how spectacular the view was from this elevated position; to say it was impressive would be an understatement. The monastery, as I knew only too well, looked out across the plain of Mush and the Eastern Euphrates, beyond which were the foothills and peaks of the Armenian Highlands. Yet the monastery itself is sheltered beneath hilly slopes to the southeast, south, and west, which would have afforded it some degree of protection from the elements during the long, harsh winters.

For an hour or so, I followed the course of the perimeter wall, obtaining photos, getting video footage, and taking in the ambience, always with one of our hosts by my side. Scattered everywhere were potsherds of all shapes and sizes, which I could see embraced a time frame from medieval times right down to the modern day. However, I was not concerned with ceramics on this occasion. I wanted to find evidence that the site had been occupied prior to the arrival of Christianity in the fourth century. Yet, in all honesty, I found nothing of interest, even though there was every possibility that a settlement from a former age could have occupied a position higher up the hill, closer to its summit perhaps.

One legend fervently believed by the monks of Yeghrdut tells how near “a small workshop” somewhere beyond the monastery, a concealed copy of the “Old Testament” was found. It was apparently seen as a gift of the eagle, presumably the one that lived in the holy evergreen tree.

13

The implication of this chance discovery is that the book belonged to an age that antedated the monastery, implying that the site was important even before the arrival of Gregory the Illuminator in the fourth century.

IS THIS EDEN?

It was very difficult to take in the setting during this one brief visit. My sense, however, was that the monastery had been deliberately left to fall into decay. The site had been neglected, this was clear, and no one really seemed interested in its history or preservation. It was difficult to come to terms with the fact that until 1915 Yeghrdut had been a thriving monastery, as well as a tranquil place of healing for Armenians and Kurds alike. Men and women came here not just to cure ailments but also to rejuvenate both body and soul. There was a natural vitality about this site, which people believed was channeled through the holy tree and spring, the reason they took away leaves, twigs, and bark, not to mention the holy water itself.

All that is now gone. All that remains is the tranquillity of the site and its extraordinary setting, which is simply outstanding. This was the sight the monks of Yeghrdut woke up to every morning, making it easy to understand why they might have believed this was some quiet corner on the edge of Eden itself.

THE RED EARTH OF ADAM

The monks also cannot have failed to notice the absolute redness of the earth, especially the hill slope to the southeast of the monastery. It would have reminded them that the first-century Jewish scholar Flavius Josephus wrote that Adam was created out of red clay:

That God took dust from the ground, and formed man, and inserted in him a spirit and a soul. This man was called Adam, which in the Hebrew tongue signifies one that is red, because he was formed out of red earth, compounded together; for of that kind is virgin and true earth.

14

Another tradition said that after Adam’s death, he was buried by angels “in the spot where God found the dust” to fashion his body.

15

So if the monks did see the red earth surrounding the monastery as significant (and it is rarely glimpsed anywhere else in the area), then it might well have strengthened the conviction that their monastery existed close to the site where Adam and Eve lived after their expulsion from Paradise, and where afterward their son Seth and his descendants continued to live right down to the time of the flood.

A RESPITE

After completing our visit to the ruins, the elderly man and his wife opened up their home to us. Inside the large, conical tent, its opening directed toward the plain below, we sat down on a bed of brightly patterned kilim rugs that overlaid a bed of flat stone slabs. Placed in front of us was an enormous silver platter containing glasses of sweet tea and bowls of local food, including yogurt, Turkish flat bread, and salad. The kindness of these people was overwhelming, particularly as they did not know me, our guide, or the taxi driver, who were all afforded the same degree of hospitality.

I then learned something important from the fez-wearing man. He told me that somewhere on the hill slope, immediately behind the monastery’s west wall, there was once a large cave opening. Yet it had vanished after the “rich” Armenian monks had stuffed it full of “gold” prior to their rapid departure. Local people had attempted to find the cave entrance in order to reach the “gold,” but so far all efforts had come to nothing.

I found the story difficult to believe, first, because there was no sign of any cave existing today (I checked afterward), and, second, the fervent belief that Armenian monks were so rich that they simply could not carry away all their cumbersome gold treasure was quite simply fantasy. The only thing it did do was remind me of the legends regarding the Cave of Treasures, where Adam, Eve, Seth, and their family had lived and where they were supposedly buried upon their deaths. Was the role model for the Cave of Treasures around here somewhere, if not close to the monastery, then in the foothills of the mountains immediately to the south of Yeghrdut? Was it there that the secrets of Adam, inscribed either on steles or pillars, would one day be found? Or was it north of the plain of Mush, somewhere in the vicinity of Bingöl Mountain? There were no hard and fast answers, and for now the matter would have to rest there.

One other piece of information I picked up was that around fifteen years before, workmen had arrived one day and broken down whole sections of the monastery’s remaining walls, with the resulting piles of rubble being carried away in waiting trucks. Hearing this instantly made me concerned about the fate of the remaining ruins, which are not protected in any manner, and so could, presumably, be destroyed at any time.

Shortly after that it was time to leave. A thunderstorm was close by, and once it hit, any resulting flash floods could make driving back down the mountainside treacherous. So as the taxi now began to make its descent, I watched awestruck as a rolling gray cloud came in from the west and seemed to follow the course of the Euphrates, sending out lightning flashes that struck the plain of Mush and even the waters of the river itself. No wonder the Semitic peoples of Syria and Canaan came to believe that the abode of the god El was to be found in this otherworldly Land of Darkness.

AN UNEXPECTED JOURNEY

That night and the next day I recorded my thoughts and impressions about the trip to the monastery. There was a sense that I had achieved what I had come here to do, but I wanted to go back one more time, and this I managed to do on Wednesday, September 12, with the same taxi driver, although this time with a new guide, a social worker named Idris, who spoke perfect English. He knew every village, large and small, on the plain of Mush, as he visits them as part of his day-to-day job. We shared a mutual passion for keeping alive the rich cultural heritage of the region and so very quickly became friends.

The following day Idris asked if I would like to accompany him the next day to a village called Muska, not far from Bingöl Mountain. He had friends there who were Alevi and thought this might be an ideal opportunity for me to speak with them about their beliefs and practices. Even though I was due to leave Mush early the morning after that, this was too good an opportunity to miss, so I said yes.

I asked Idris about the situation regarding access to Bingöl Mountain, as I understood it was a virtual no-go area because of the recent army offensives. He said we would be fine and that if we did encounter any PKK units in the hills, he knew what to say (Kurdish sympathy among the local population runs very high indeed). With that, I accepted finally that I might get to glimpse Bingöl Mountain, at least from a distance, which is something I had almost abandoned any thought of achieving on this journey of discovery.

40

A TRIP TO PARADISE

F

riday, September 14, 2012. The drive by

dolmus

(a Turkish minibus) from Mush to the Alevi town of Varto, in the foothills of the Armenian Highlands, was breathtaking. After leaving the great plain, the road follows the course of the Eastern Euphrates, which runs alongside the road for part of the way. Once that had veered away toward the east, the vehicle climbed ever higher until, finally, we entered Varto itself. The town is a bustling hive of activity even in the baking hot sun, and having left behind the dolmus, we journeyed on foot until we reached a local hospital, where Idris picked up a car for us to complete the journey (it belonged to a work colleague).

After departing Varto, we moved into a beautiful green landscape, utterly different from the dusty, volcanic earth that proliferates on the plain of Mush, and very soon my eyes became focused on something I never expected to see on this journey—the summit of Bingöl Mountain looming up ahead. Seeing it as a single mountain is in fact inaccurate, for Bingöl is in reality a north-south oriented ridge, or massif, with two separate peaks, linked by a saddleback indentation.

MOUNTAIN LION

Unbelievably, the car journey took us right alongside the mountain, which was on our right-hand side at a distance of no more than 4–5 miles (6.5–8 kilometers). What I saw transfixed me, for the twin peaks give the mountain’s elevated summit the likeness of a large feline, most obviously a lion, its protruding head, shoulders, and forelegs made up of the northern peak, with the saddleback indentation and southern peak creating the creature’s body, hind legs, and tail (see

plate 31

). The whole thing looks as if it is emerging from the mountain’s rocky surface in order to rise into the sky. The form is unmistakable and cannot have been missed by those who inhabited the region in the past. Of course, not everyone is going to interpret this rock simulacrum as a lion, although the likeness is striking enough for it to have impressed some people along the way, including perhaps the Armenians who would come here each spring to venerate Anahita, the goddess of fertility and the waters of life. She is depicted in Persian religious art as a shining being standing on a lion.

PEOPLE OF TRUTH

A lion sitting astride a world mountain, guarding the axis mundi or world pillar as Bingöl Mountain appears to do in Armenian myth and legend, reminded me also of a similar leonine beast featured in the creation myth of a Kurdish religion named Ahl-e Haqq, which means “People of Truth.” Although this ethnoreligious group, known also as the Yâresân, exists mostly in Iraqi Kurdistan and northwest Iran, some still remain in remote parts of eastern Turkey. According to them, a charismatic leader named Sultan Sahak founded the Ahl-e Haqq religion during the fourteenth century, although beyond that their origins remain obscure.