God and Mrs Thatcher (18 page)

Read God and Mrs Thatcher Online

Authors: Eliza Filby

Margaret Thatcher’s first foray into preaching came two years into her leadership in 1977, on the occasion of the inaugural memorial lecture for the Conservative Chancellor Iain Macleod. Thatcher began on a point of historical fact. Before the Conservative Party had been the party of capital or property, it ‘began as a church party’ she affirmed. This was indeed true but it was not an outdated mode of Erastianism that Thatcher was there to champion, but a notion of divine liberty, one that had very little to do with traditional Conservatism and was more in tune with nineteenth-century liberalism. Margaret Thatcher’s explicit tying of Christianity, individualism and Conservatism is worth quoting at length:

Our religion teaches us that every human being is unique and must play his part in working out his own salvation. So whereas socialists begin with society, and how people can be fitted in, we [Conservatives] start

with Man, whose social and economic relationship are just part of his wider existence. Because we see man as a spiritual being, we utterly reject the Marxist view, which gives pride of place to economics.

53

The following morning

The Times

praised Thatcher as ‘a better Lutheran than Luther’ with the speech representative of the best ‘English Protestant Christian tradition’ evoking the spirit of Wycliffe, Cranmer, Adam Smith, Wesley and Gladstone. Admittedly, this was not a very ‘Conservative’ list, but then as

The Times

recognised, the contents of the speech was not very Tory at all and more in line with the dissenting religious tradition: ‘Is the view that a man has a religious duty to decide his own life rather than having others decide it for him, a view that now belongs to the right?’ it legitimately questioned. Given Thatcher’s spirited defence of the individual,

The Times

wondered whether the new leader was seeking to transform the party of the Cavaliers into the party of the Roundheads: ‘King Charles I would have been surprised to be told that the men who asserted their individualism against his divine right to rule were really reactionaries, and that he was the progressive.’ Margaret Thatcher, not yet leader for two years, was already playing mind games with the English historical consciousness.

54

Edward Norman wrote a letter in support of Thatcher’s speech, wryly adding that the Church of England hierarchy should read it. Not everyone was convinced though. The Vicar of Harwell and Chilton in Oxfordshire challenged Thatcher on her ‘individualism based on merit’ and ‘a religion of “works”’, which he posited was the ‘very opposite of Lutheran teaching’.

55

Never one to shy away from an argument, Thatcher wrote a lengthy reply to

The Times,

in which she advised the vicar to read the works of Adam Smith:

Smith argued … by harnessing men’s natural impulse to improve their own condition and that of their families as well as to deserve the

approbation of their fellow-men, the market economy visibly brought great benefits to the greater number. Smith never suggested that self-interest alone was sufficient to bring the Good Life, or that man can live by bread alone. By contrast, Marx’s dialectical materialism gave pride of place to economics … perhaps the Vicar will again read Marx for himself after he has laid down Smith. He appears to believe that Marx stood for equality, as well as for benevolence and other Christian virtues. Surely then, he must have asked himself how, if this be so, can it be that wherever Marxist rule is imposed, as it is on a third of suffering mankind, it leads visibly to cruelty, misery, callousness, selfishness, new crying inequalities.

56

Margaret Thatcher took to the pulpit a little over a year later in 1978 in a speech in the parish of St Lawrence Jewry in the City of London. Alfred Sherman was on hand to help with the drafting and suggested she speak on the revitalisation of Christianity and the Protestant work ethic.

Daily Telegraph

journalist T. E. Utley was also brought on board for expertise, yet he questioned whether it was wise for Thatcher to speak on Church matters, which risked upsetting Anglican voters just before an election:

Public interest would be captured by using some of this autobiographical material … it is not a good idea to have the Tory Party leader leaping in to theological controversy between the liberal and conservative wings of the Church unless she makes it perfectly clear that she is doing so in a private capacity.

57

Speechwriter Simon Webley, who also helped in the drafting, did not share Utley’s desire for caution. With a sense of urgency Webley pressed Thatcher to address the decline of Christianity and the debilitating influence of ‘humanistic socialism’ within society. ‘What has happened to the Christianity of our forefathers?’ Webley asked before

offering up the answer: ‘It has been subsumed by an arid materialism concerned with the Gross National Product rather than the will of Almighty God.’ Webley entreated Thatcher to preach a message of individual responsibility and the doctrine of original sin. In Webley’s view, the public needed to be told that ‘the evils of society are not due to the accident of class, education, income or region but to the inherent frailty of the individual himself’. Conscious that this would not find favour amongst the ecclesiastical and political class, Webley nonetheless drew upon the words of Montesquieu: ‘When religion is strong the law can be weak, when religion is weak the law must be strong.’ He too rather boldly suggested that she end with a quote from Proverbs: ‘Righteousness Exalteth a nation.’

58

Margaret Thatcher delivered a speech appropriately entitled ‘I believe’ incorporating Utley’s suggestion that she reference her personal faith and Webley’s ideas about the political application of the Fall:

We were taught always to make up our own minds and never to take the easy way of following the crowd. I suppose what this taught me above everything else was to see the temporal affairs of this world in perspective. What mattered fundamentally was Man’s relationship to God, and in the last resort this depended on the response of the individual soul to God’s Grace … though good institutions and laws cannot make men good, bad ones can encourage them to be a lot worse … Christianity offers us no easy solutions to political and economic issues. It teaches us that there is some evil in everyone and that it cannot be banished by sound policies and institutional reforms; that we cannot eliminate crime simply by making people rich, or achieve a compassionate society simply by passing new laws and appointing more staff to administer them.

59

Thatcher’s speech received little by way of reaction, partly because the

Daily Telegraph

journalist present had failed to file a report and

The Times

was then on strike. This may have been for the best, given that her Cabinet colleagues reportedly did not share Thatcher’s enthusiasm for such sermonising. According to Sherman, the years in opposition were about saying ‘as little as possible about anything’.

60

Margaret Thatcher’s message and image took time to get right with the general public, yet her affinity with the Tory Party was almost immediate. Her first party conference in 1975 had the feel of a leader reconnecting with their flock with the

Daily Mail

full of praise for the Conservative leader who had reportedly ‘electrified her supporters at Blackpool … like no party leader has done in the 1970s’.

61

It was true that Thatcher was in sympathy with rank-and-file Tories in a way that none of her rivals ever were. On seeing her perform at party conference, Harold Macmillan remarked on the contrast with his own experiences: ‘We [his Cabinet] used to sit there listening to these extraordinary speeches urging us to birch or hang them all or other such strange things. We used to sit quietly nodding our heads … But watching her … I think she agrees with them.’

62

Conservative strategists, though, were fearful that Margaret Thatcher appeared

too

Conservative,

too

English, and a bit too middle class. This was certainly how those at the US embassy in London perceived her. In a report for the US State Department on the new Leader of the Opposition, Thatcher was described as the ‘genuine voice of a beleaguered bourgeoisie … [a] quintessential suburban matron, and frightfully English to boot’.

63

This was a perception that Thatcher herself was particularly keen to refute. In a piece for the

Daily Telegraph,

Thatcher refuted the accusation that her politics were class-based:

If ‘middle-class values’ include the encouragement of variety and individual choice, the provision of faith incentives and rewards for

skill and hard work, the maintenance of effective barriers against the excessive power of the state and a belief in the wide distribution of individual private property, then they are certainly what I am trying to defend.

64

Margaret Thatcher, like most leaders who hope to be prime ministers, wisely avoided class labels. Meanwhile, Tory strategists aimed not only to win back traditional Conservative voters but that their policies would have a broader appeal. In short, the hope was that the affluent workers of the 1960s would become the upwardly mobile of the 1980s – they did.

The specific challenge of transforming Margaret Thatcher’s image fell to smooth-talking, cigar-smoking TV executive Gordon Reece. The match was less Professor Higgins to Eliza, more Hollywood movie mogul to a young starlet. If Shirley Williams could be seen as having the boyish charm and sophistication of Katharine Hepburn and Barbara Castle, and the bolshiness of Bette Davis, then Margaret Thatcher was to be marketed as the fearless and determined Joan Crawford ‘on the up’. Gone was the suburban shrill as Thatcher lowered her voice an octave, slowed it down and sharpened the intonation. She binned the hats and pearls as Reece told her to be normal and had her performing set pieces in supermarkets or doing the washing up. By the time the election came round, Thatcher’s confidence in her own ability had grown. In 1978, her speechwriter Ronald Millar took her to see the new musical

Evita

by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. She wrote to Millar in thanks:

It was a strangely wondrous evening yesterday leaving so much to think about. I still find myself rather disturbed by it. But if they [the Peronists] can do that without any ideals, then if we apply the same perfection and creativeness to our message, we should provide quite good historic material for an opera called Margaret in thirty years’ time!

65

The genius of the Conservative campaign in the election of 1979 was its translation of complex economics into a populist message, which was projected through its leader. The image of Margaret Thatcher holding up two shopping bags of groceries – one blue, full to the brim, and the other red, half empty – crystallised in one shot how economic theory related to people’s everyday lives and the Conservatives’ commitment to beat inflation.

Conservatives were, of course, fortunate with the ‘Winter of Discontent’, which turned an already exhausted British public firmly against the unions and, more importantly, made them sceptical of the Labour Party’s ability to deal with them. When, in February 1979, Archbishop Coggan initiated talks between the three party leaders, Thatcher agreed, but only on the condition of Callaghan’s presence. Callaghan, however, rejected the call: a stance that showed Thatcher to be acting in the national interest without actually having to concede a word.

66

From that moment, she went on the attack. Incidentally, so did the archbishop, who in a sermon soon afterwards labelled the protest as ‘pitiless’ and ‘irresponsible’.

67

The Winter of Discontent was important for another reason: in reinforcing fears about national decline. The understanding that Britain, the nation that had once kept Europe free, but was now going to the dogs, proved to be a potent narrative and one that the Conservatives willingly exploited: national renewal was made a key election pledge. In the end, Britons went with a woman about whom they knew relatively little but on whom they were willing to take a chance as Thatcher achieved her largest share of the popular vote in all of her three election victories.

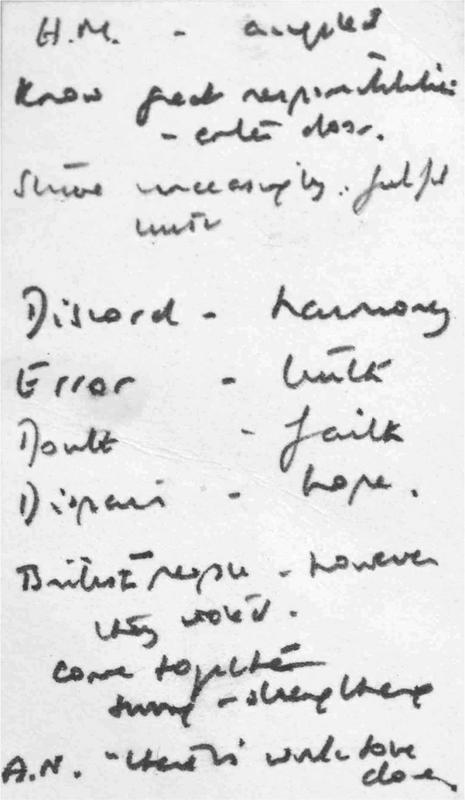

It is customary for newly appointed prime ministers to express some vague words of thanks in their first address outside Downing Street. In 1970, Edward Heath had uttered some forgettable sentiments about recreating ‘one nation’. Before the 1979 result had been confirmed, Thatcher had asked her chief speechwriter and dramatist Ronald Millar to prepare something for her to say outside No. 10. When Millar informed her of his idea for the prayer, Margaret wept. When the

moment finally came she slowly delivered the words, her eyes looking directly into the camera and only once peering down to look at the reminder card carefully positioned in her palm:

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony.

Where there is error, may we bring truth.

Where there is doubt, may we bring faith.

And where there is despair, may we bring hope.

Margaret Thatcher’s handwritten reminder for her first words as Prime Minister outside Downing Street