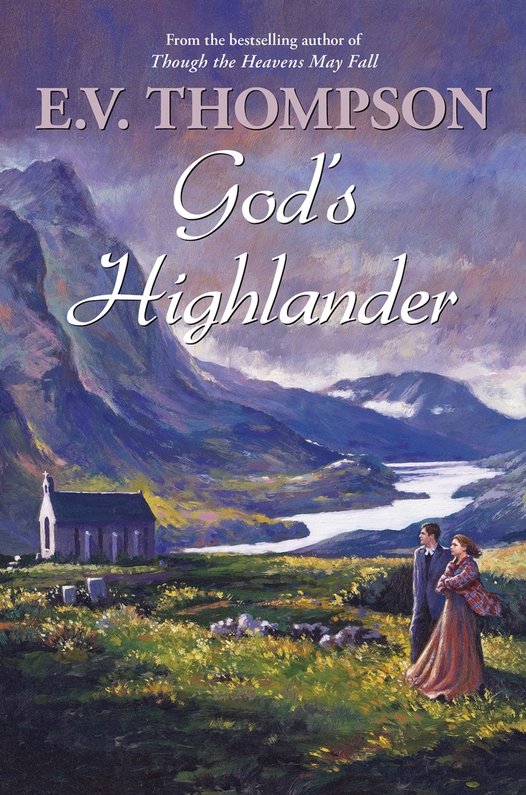

God's Highlander

Authors: E. V. Thompson

By the same author

Â

THE MUSIC MAKERS

CRY ONCE ALONE

BECKY

GOD'S HIGHLANDER

CASSIE

WYCHWOOD

BLUE DRESS GIRL

TOLPUDDLE WOMAN

LEWIN'S MEAD

MOONTIDE

CAST NO SHADOWS

SOMEWHERE A BIRD IS SINGING

WINDS OF FORTUNE

SEEK A NEW DAWN

THE LOST YEARS

PATHS OF DESTINY

TOMORROW IS FOR EVER

THE VAGRANT KING

THOUGH THE HEAVENS MAY FALL

NO LESS THAN THE JOURNEY

CHURCHYARD AND HAWKE

THE DREAM TRADERS

BEYOND THE STORM

Â

The Retallick Saga

Â

BEN RETALLICK

CHASE THE WIND

HARVEST OF THE SUN

SINGING SPEARS

THE STRICKEN LAND

LOTTIE TRAGO

RUDDLEMOOR

FIRES OF EVENING

BROTHERS IN WAR

Â

The Jagos of Cornwall

Â

THE RESTLESS SEA

POLRUDDEN

MISTRESS OF POLRUDDEN

Â

As James Munro

Â

HOMELAND

© E.V. Thompson 1989

First published in Great Britain 1989

This edition 2011

Â

ISBN 978-0-7090-9157-8

Â

Robert Hale Limited

Clerkenwell House

Clerkenwell Green

London EC1R 0HT

Â

Â

The right of E.V. Thompson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Â

Â

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Typeset in 10.5/13.5pt Sabon

Printed in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group,

Bodmin and King's Lynn

Title Page

Copyright Page

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

Thirty-six

Thirty-seven

Thirty-eight

Thirty-nine

Forty

Forty-one

Forty-two

Forty-three

Forty-four

Forty-five

Forty-six

Forty-seven

Forty-eight

Forty-nine

Fifty

Fifty-one

Fifty-two

Fifty-three

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates and men decay:

Princes and lords may flourish or may fade;

A breath can make them, as a breath has made;

But a bold peasantry, their country's pride,

When once destroyed, can never be supplied.

Â

OLIVER GOLDSMITH, âThe Deserted Village'

T

HE TINY STEAM-POWERED launch sliced through the deep green waters of Loch Eil. In its wake an expanding herringbone pattern gathered strength, only to die when it touched the loch shore, no more than a quarter of a mile on either hand. From the vessel's tall thin funnel a plume of black smoke rose high into the air before changing form and becoming one with the clear mountain air. To the north and the south, steep-sided mountains took the coughing of the steamer's engine and tossed the sound back again, sending long-necked cormorants beating a retreat across the surface of the narrow loch. High above the water a lone gliding eagle wheeled away to seek an afternoon meal in quieter glens.

The long ridges of the mountains still wore mantles of white, but on the wooded lower slopes the snow was melting fast, tumbling down the mountainsides in a skein of streams, rivulets and water-falls to the loch, more than two thousand feet below.

On the fish-stained deck of the steam-launch a young man stood with legs braced wide against the movement of the vessel. Dressed in a sober black suit, he sucked in lungfuls of the heady cool Highlands air. The Reverend Wyatt Jamieson had been treated to a surfeit of mountains and lochs during the uncomfortable three-day voyage from Glasgow, but he was enjoying every moment. For him this was a triumphant return to the land of his birth.

An aborted career in the Army had been followed by studies at university in Edinburgh. Now, after two years working as an assistant minister in a Glasgow slum, he was returning, at the age of twenty-eight, to the Highlands of Scotland, where he belonged.

A change in the rhythm of the steam-powered engine broke into

Wyatt's thoughts as the launch changed direction, heading towards a small lop-sided landing-stage no more than half a mile ahead.

Scattered haphazardly about the flimsy landing-stage were a number of low-built single-storey houses. Some were of stone, others of mud and mortar. All had thatched roofs. This was the village of Eskaig, where Wyatt was to be the new resident minister for the Church of Scotland. The heart of a parish that included many square miles of Highland territory.

The people who inhabited this lonely place were of a breed unlike any other in the land. They were âHighlanders'. Fiercely proud of their heritage and independence, they had been rendered tragically vulnerable by that very independence in this the fifth year of the reign of the young Queen Victoria.

Donald McKay, coxswain, engineer, sole owner and crew member of the little steam-launch, removed a rough-briar pipe from his mouth and used it to point ahead to Eskaig.

âIt would seem you're expected.'

The sunlight slanting down over the mountains was reflected from the surface of the loch, and Wyatt raised a hand to shield his eyes against the glare. At the water's edge a small crowd of people was gathering, brought from their homes by the sound of the boat's engine.

âI wasn't expecting a welcoming partyâ¦.'

âDon't hold your breath waiting for welcoming words, Minister. You're here to take the place of Preacher Gunn. He was in Eskaig for forty years and might have lasted a full half-century had he not been hounded to death by the landlord's factor.'

Donald McKay's quiet voice and gentle west-coast accent could do nothing to soften the harshness of his words. Shifting his gaze to Wyatt, he added: âLeastways, that's what's being said â and you're here as the landlord's man.'

âIs there any truth in it?'

âEnough.'

Some of Wyatt's pleasurable anticipation seeped away. He wondered why he had been told nothing of the situation in Eskaig when he had visited the Moderator's office in Edinburgh. Although it was not really surprising. The Highlands might as well be on another planet as far as churchmen in Scotland's capital were concerned. Few

of the men responsible for the spiritual needs of the Highland communities had ever set foot here.

Wyatt was aware, too, that he

was

the landlord's man â presented to the living by Lord Kilmalie himself. Wyatt had a special reason for accepting a post as preacher of Eskaig and was convinced he could serve the community well. Perhaps he should have paused to consider whether or not they would

want

him to serve them.

By the time the steam-launch eased its way slowly alongside the ageing jetty the waiting crowd had grown to around sixty, and Wyatt looked in vain for a smile of welcome. The faces of the men were set in grim dour lines. The expressions on the faces of the women were more animated â but only because they were less inclined to disguise their displeasure.

When the launch bumped against the jetty the structure groaned alarmingly. Unconcerned, Donald McKay took a turn around a bollard with a mooring-rope. When he was satisfied the boat was secure McKay heaved Wyatt's weighty leather chest ashore.

âI wish you good luck, Minister, but I fear it's more than wishes you'll be needing here in Eskaig.'

Clutching a bulging canvas bag, Wyatt was following his chest ashore when a small dried-up man stepped from the crowd. Grey-haired and elderly, the man wore a suit of dark best serge similar to Wyatt's. More coarsely woven than the one worn by the minister, many years of assiduous brushing had removed the last vestige of nap from the material.

âDon't cast off yet, Boatman. You'll no doubt be taking the pastor away with you again when I'm through talking.'

âOh? And will you be paying me his fare, Angus Cameron? I've been given money to bring the minister as far as Eskaig â and not a single mile farther.'

âYou can beg his fare from the man who sent him to Eskaig unasked: Lord Kilmalie.'

The spokesman's words provoked a growing murmur of assent from the men and women standing on the loch-bank behind him.

âSince I'm the subject of your discussion, perhaps I might say something on my own behalfâ¦.' Wyatt set his bag down beside the chest and confronted the hostile Eskaig spokesman.

âMy name's Wyatt Jamieson, and I've come here as your new

minister. I know I'll never be able to take the place of Preacher Gunn, but I'll do my best â if you'll give me the opportunity.'

Angus Cameron was taken by surprise by Wyatt's words and he cast an uncertain glance over his shoulder at his fellow-villagers before speaking again.

âWe've nothing personal against you, Minister, you understand, but the people of Eskaig will choose their own preacher. We'll not have one foisted upon us by a landlord who's never set foot within a hundred miles of Loch Eil for twenty years.'

âLord Kilmalie's not an absentee landlord who cares nothing for his tenants. He's a sick man, unable to travel. He's forced to leave his affairs in the hands of his factorâ¦.'

A howl of derision interrupted Wyatt's words, and a woman's voice rose above the rest, shrill and excited: âWe want no city man here. We need a pastor who speaks our own tongue. Tell him, Angus.'

âDon't waste your breath. In a few more years there'll be no one left in the Highlands. He'll be preaching to an Englishman's sheep.'

This voice was a woman's, too, but the words were spoken in Gaelic, the predominant language of the Highlands.

Looking beyond the villagers, Wyatt glimpsed a tall dark-haired girl standing in the midst of a small group a few paces apart from the others. Barefoot, she carried a plaid shawl about her shoulders. The men with her wore soft grey bonnets and had shepherd's plaids wrapped about their bodies.

âI'm no city man,' Wyatt replied in Gaelic that was as fluent as that used by the mountain woman. âI was born in

Eilean an Fhraoich

â in the Isles. My father was the preacher there until he was dispossessed, along with his people. He brought them along this very road to take a boat to Canada from Fort William. He would have gone with them, had the Lord not taken him first. He's buried right here, in Eskaig. As for the preaching, I was proud to wear a shepherd's plaid as a boy, and I know from experience there are worse congregations than a flock of sheep.'

Wyatt's reply brought a fleeting smile to more than one tense face. Pressing home his temporary advantage, he asked: âWill someone show me to the minister's manse? I'd like to be well settled in before dark.'

âYou'll not be settling in Eskaig, Minister. Go back to where you

came from. As I've told you, we'll not accept a landlord's man here.'

âI'm the

Lord's

man, Mr Cameron. Appointed to preach

His

word â not those of any landowner. If you won't show me the way and help with my things, I'll need to manage as best I can by myself.'

With a swift movement that revealed unexpected strength, Wyatt swung the laden chest to his shoulder and held it in place with one hand. Tucking the bag beneath his other arm, he accepted his stout walking-stick from the boatman.

âThank you for your company on the voyage, Donald. You can go now. I'll be all right.'

Unlooping the mooring-rope from the bollard, Donald McKay removed the pipe from his mouth and raised it in salute. âAy, Minister. I do believe you will.'

As the engine beat out its noisy rhythm once more, Donald McKay allowed the vessel to drift clear of the jetty before engaging forward gear. Executing a wide turn, he steered the boat away from Eskaig without a backward glance.

The villagers of Eskaig were numerous enough to block the road from the jetty completely, but whether or not they intended to bar Wyatt's way was never put to the test.

A number of hard-ridden horses were heading towards Eskaig along the rough road that followed the shoreline. As the riders drew closer Wyatt could see that all except one wore the red tunic of a yeomanry regiment. There was an officer with the militiamen, but it soon became apparent who was giving the orders.

As the part-time soldiers neared the villagers they began to draw in their mounts â but not the civilian who rode with them. He drove his horse on into the crowd, scattering villagers on either hand before hauling the animal to a sliding halt in front of Wyatt.

âWhere the hell do you think you've been? I've just ridden to Fort William and back seeking you.'

It was an English accent, and the man's voice was no more gentle than his riding. âWere you not given my message before leaving Edinburgh?'

The rider made no attempt to dismount, and his horse danced nervously in front of Wyatt, bothered by the crowd about him.

âI was given a great many messages before sailing from

Glasgow

. I don't recall one from you among them.'

Wyatt did not need an introduction to know the man sitting on the horse was the factor in charge of Lord Kilmalie's Highland estates. It explained the man's arrogance. John Garrett's position made him the most powerful man in the district.

âI sent word you were to come no farther than Fort William. I said I'd bring you from there in order to avoid a confrontation with this rabble. What's that damned lieutenant doing? MacGregor, drive these people off the road and send them about their business.'

The militiamen sat their horses uncertainly at the edge of the crowd. Now, at a less than wholehearted order from their youthful commanding officer, they kneed their horses forward, driving the villagers before them.

Only the small group of plaid-wearing Highlanders held their ground. There were some nine or ten of them, and they stood to one side of the uneven roadway, watching the proceedings with a detached interest.

Pointing in their direction, John Garrett called: âGet rid of

them

, too. Make sure they move off with the others.'

A number of militiamen wheeled their horses about to obey his instruction, but one of the grey-bonneted Highlanders, a large man with a red beard tinged with grey, stepped forward. He addressed John Garrett in halting English.

âWe've come down to speak to you, Factor. There are rumours we're to be cleared from our landsâ'

John Garrett cut the older man's words short. âRumours are for old women, Eneas Ross. When there's a need for you to know anything

I'll

tell you. Until then be sure your rent's paid on time. Move them on, Lieutenant.'

The factor signalled impatiently, and the militiamen drove their horses forward, but Eneas Ross stood firm. He was still looking towards John Garrett when one of the horses cannoned into him, knocking him to the ground.

There was an angry murmur of protest from the small group of Highlanders, and two of the younger men stepped forward quickly. Wyatt thought he saw the glint of metal in the hand of one of them â and some of the militiamen saw it, too. Without waiting for an order, half a dozen of the part-time soldiers drew sabres from their scabbards.

Hurriedly dropping his chest and bag to the ground, Wyatt stepped forward to place himself between militiamen and Highlanders.

âThere's no need for steel.' He addressed his words to the militia lieutenant, at the same time using his stick to arrest the downward movement of the sabre-blade.

âAttend to your own business, Minister. Leave me to attend to mine.' The lieutenant's eyes were on the Highlanders as he spoke.

âBefore becoming a minister I was a captain in the Seventy-Second Regiment â a

regular

officer. I could no doubt teach you a thing or two about fighting â and I'm telling you this isn't the time.'

The lieutenant shifted his gaze to the preacher, and now there was a part-time soldier's respect for a professional in his eyes. Wyatt had mentioned one of Scotland's finest Highland regiments and, as a captain, Wyatt outranked the lieutenant.

Taking advantage of the situation he had created, Wyatt called softly to the Highlanders in their own language: âGo. Quickly now, before there's blood spilled.'

The two younger men helped Eneas Ross to his feet, but he shook them off and stooped to pick up the plaid which had fallen to the ground. After looking briefly in Wyatt's direction he turned and walked away, the younger men falling respectfully into step behind him.