God's War: A New History of the Crusades (119 page)

Read God's War: A New History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Christopher Tyerman

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Military History, #European History, #Medieval Literature, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Religious History

Almost half a century later, two old men encountered by a German pilgrim by the Dead Sea turned out to be French Templars captured at Acre in 1291. They had worked for the sultan, married and had children, living in the southern Judean hills, entirely isolated and ignorant of events in the west. They now became minor celebrities. They and their families were shipped back to Europe and received with honour at the

papal court at Avignon before retiring on pensions to end their days in peace. What they, their wives, children or new neighbours made of this turn of fortune is unknown. Yet their fate stood as a suitably confusing epitaph for Frankish Outremer: glamour, courage, strain, wishful thinking, strenuous endeavour, the international stage and unmistakable domesticity.

62

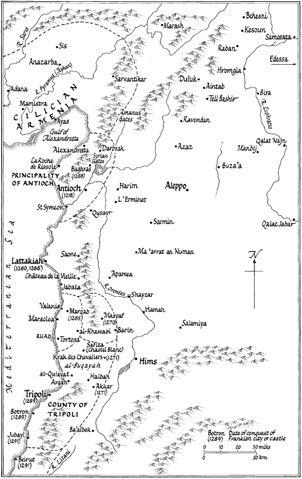

21. Syria in the Thirteenth Century

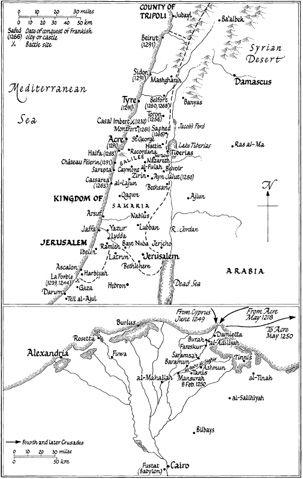

22. Palestine and Egypt in the Thirteenth Century

23

The Defence of the Holy Land 1221–44

The failure of the Damietta campaign did not end the great crusading enterprise Innocent III had initiated in 1213. Eleven days after the city was returned to Ayyubid control, Peter des Roches bishop of Winchester was taking the cross in England.

1

The summer of 1221 saw Cardinal Ugolino methodically recruiting crusaders and mercenaries from the lords of northern Italy, using church funds as incentives.

2

As far as Honorius III was concerned, Frederick II’s obligations still stood. They formed a central practical as well as symbolic element in papal – imperial negotiations, a process of preparation and a guarantee of sincerity. Frederick reiterated his commitment in 1223 and 1225. Philip II of France bequeathed 150,000

livres

to the project in 1223, perhaps out of a guilty conscience. The crusade continued to be used as a means of resolving political disputes, as in Marseilles in 1224, as well as an expression of private devotion.

3

A Parisian couple, Renard and Jeanne Crest,

crucesignatus

and

crucesignata

, made their pious and financial dispositions in 1224–5 before departure.

4

Stories of the Egyptian debacle of 1218–21 by witnesses such as James of Vitry and Oliver of Paderborn were circulated widely. The messy legal ramifications surrounding absent, deceased or presumed dead crusaders’ property kept the reality of crusading painfully alive by engaging the energies of their squabbling neighbours, relatives and local law courts in some cases for over fifteen years.

5

Contributions were still forthcoming. In England in 1222 a tax was levied on behalf of the kingdom of Jerusalem, proceeds of which were supposed to subsidize crusaders to the east. John of Brienne, king of Jerusalem visited the west in 1223, trying to drum up aid. Papal legates and local bishops continued to preach and round up

crucesignati

; Master Hubert, recruiting in England in 1227, kept a written register of those who had taken the cross.

6

For the first time the new preaching

order of the Dominican friars was employed in England under the patronage of Peter des Roches.

7

Within a few years they and the Franciscans came to dominate the

verbum crucis

, the word of the cross.

More generally, the decades after 1221 saw the ‘business of the Holy Land’ embedded into the religious culture of western Christendom. Away from specific campaign appeals, the special prayers, liturgy, bell-ringing, processions and invitations to donate alms that had been established since 1187 assumed habitual places in the devotional round of the faithful laity. The democratization of penance after the Fourth Lateran Council through oral confession, the improvement in the educational standards of the clergy and the extra-parochial presence of friars and, for the prosperous, private confessors was matched and reflected by a growing prominence of lay spirituality expressed in religious confraternities, which sprang up across Europe, most obviously in towns, and in the personal lives of lay

dévots

. Stress on the spiritual life and moral behaviour of individuals recognized the validity and value of personal and collective lay religious observance. The crusade epitomized just this sort of secular commitment, a number of contemporary observers likening

crucesignati

to converts or even a religious order, a

religio

.

8

Crusading perceptions and practices altered in the thirteenth century. Taking the cross signalled inner spiritual commitment not limited to specific military endeavour alone. The crusade became braided with personal religious identity in a system of practical spirituality channelled through regular devotional exercises; confession, penance, alms-giving, prayer and conduct. Louis VII of France had been a pious monarch and crusader, but the role crusading played in his spiritual life, as far as external appearances are any guide, pales beside its importance to his great-grandson Louis IX. For the younger Louis, the crusade occupied a central place in his life, a means to achieve personal and spiritual emancipation, self-expression and fulfilment. Similar prominence of the crusade in a broader spiritual life of puritanical seriousness was demonstrated by another leading thirteenth-century

dévot

, Simon of Montfort the Younger. Son of the leader of the Albigensian crusades, himself a

crucesignatus

and campaigner in the east in 1240–41, it was entirely in character that in the great crisis of his life, the civil wars in England of 1263–5, Simon called on the images of crusading to sustain his cause.

9

Even for a lukewarm crusader such as Simon’s opponent, Henry III, the cross became an accepted way of displaying religious credentials, almost

regardless of whether he embarked. Henry took the cross on at least three occasions (1216, 1250 and 1271). Neither the first or last occasion represented a serious decision to campaign. The first signalled the newly crowned boy-king’s renewal of the papal protection vital to the survival of his dynasty. Fifty-five years later, the old ailing king’s gesture spoke of rededication of a soul mindful of salvation and troubled by the unfulfilled commitment of two decades before. For Henry’s uncle, Richard I, crusading had been a much more specific ambition, no less intense perhaps, but less central to his regular spiritual life or religious observances. A century on, the crusade had become, as F. M. Powicke remarked, inseparable from the air men breathed.

10

In the years after the evacuation of Damietta, the flow of

crucesignati

to the Levant never entirely ran dry, even if the 40,000 names allegedly on Master Hubert’s roll of 1227 cannot be credited. No less telling of this diffuse commitment, the stock figures of the armchair crusader, nicknamed ‘ashie’ because he stayed by his hearth, and the

décroisié

, the man who had redeemed or abandoned his vow, entered literary vocabulary and convention.

11

This pattern of constant, often low-key activity of raising men, awareness and funds set the pattern of western engagement for the rest of the century and beyond. Periodically, the involvement of one of the great lords of western Christendom lent focus to such efforts, leading to the organization of large crusading expeditions, in 1227–9, 1239–41, 1248–50 and 1269–71. Some enterprises, as in 1248 and 1269, were ostensibly sparked by a crisis, the loss of Jerusalem or Antioch. Others owed more to the political moods or demands in western Europe rather than any threat to Outremer. Contact with the east was maintained at a number of different levels, trade, pilgrimage, even diplomacy. Both Frederick II and Henry III of England maintained diplomatic relations with Ayyubid rulers, the English king using as his ambassador a Genoese entrepreneur one of whose lines was to supply the English court with crossbows.

12

THE CRUSADE OF FREDERICK II, 1227–9

The crusade that coalesced around Frederick II in the late 1220s has tended to be dismissed as a sideshow, a self-indulgent and politically inept expression of the hubris of a ruler scarcely bothered by the motives that drove most crusaders, an expedition contradictory in genesis and barren in result. This view distorts. Polymath, intellectual, linguist, scholar, falconry expert and politician of imagination, arrogance, ambition and energy, Frederick II was no less sincere in his crusading ambition than Richard I. The cause took a central place in Frederick’s policies for almost a decade and a half, its implementation risking disaster at home and defeat abroad. Only in the hindsight of the decline of the kingdom of Jerusalem after the 1240s and the simultaneous parting of the ways between papacy and empire in the west did the events of 1227–9 come to appear futile, eccentric or irrelevant. At the time, for all his political jockeying, Frederick’s actions exposed an ambition inexplicable without a conventional religious purpose.

13

Although attracting large numbers of recruits, the organization, leadership and military core of Frederick’s expedition depended on the tight control imposed by central finance in the form of royal or ecclesiastical subsidies to individual leaders as well as lay and clerical taxation. As such, it probably constituted the most professional expedition to the Holy Land to date in the sense that many, perhaps most of the troops involved were paid as well as transported by their employers. Although conceived as an exercise in papal–imperial cooperation, Frederick’s failure to depart as promised in 1227 caused the new pope, Gregory IX, to excommunicate him, even though the reason for delay, illness, was genuine. Frederick’s determination to proceed regardless in 1228 in turn placed the pope in a false position as his ban failed to deter thousands of crusaders and had minimal impact in Outremer. The scene of the Christian emperor wearing his crown in the church of the Holy Sepulchre in March 1229 while hotly pursued by clerics eager to place the Holy City itself under an interdict was hardly edifying. Neither were papal efforts to prevent a church crusade tax being raised in Frederick’s lands, which papal armies were invading.

However, Jerusalem was restored by treaty, without bloodshed. What Richard I had failed to win by force and the Fifth Crusade had rejected as unworthy or unworkable, Frederick achieved through dogged negotiation, in the teeth of the pope’s enmity. The three holiest sites, Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth, were restored to Christian hands; the kingdom of Jerusalem given a new viability with increased territory and strengthened fortifications in cities and castles. If Frederick’s campaign marked the culmination of Innocent III’s crusade, it also marked the greatest challenge to Innocent’s vision of papal monarchy. At least in the emperor’s eyes, it seemed to vindicate the independent imperialism of a Hohenstaufen empire that Frederick had bullyingly tried to impose on the states of Outremer. Frederick’s campaign possessed a Janus-like quality, harking back to crusading precedent while offering fresh diplomatic, political and logistic solutions. One of the expedition’s more bizarre consequences certainly caught echoes of Innocent’s crusade while casting auguries for the future. At the moment of Frederick’s triumphal appearance in Jerusalem, his southern Italian lands were being attacked by papal forces under the joint command of John of Brienne and Cardinal Pelagius.

14

In the event, the reunion of these two sparring partners of the Fifth Crusade in an attempt to dismember the power of a current crusader was no more successful than their previous association.

Like many thirteenth-century rulers, Frederick II was a serial

crucesignatus

. He first took the cross at his coronation as king of Germany at Aachen in July 1215. There, probably deliberately, he aped his father Henry VI’s ceremony at Worms in December 1195 by personally presiding over the mass distribution of crosses to his new subjects.

15

The problems encountered in establishing his rule prevented Frederick honouring this vow, yet the obligation remained indelible. At his imperial coronation in Rome in November 1220, he again received the cross, this time from Cardinal Ugolino, a personal confrontation that bore bitter fruit when the cardinal, as Pope Gregory IX, excommunicated Frederick seven years later. Frederick publicly vowed to help the Holy Land twice more, at conferences at Ferentino in March 1223 and San Germano in July 1225, ten years to the day (25 July) since he had first taken the cross. This proliferation of commitment reflected the reverse of empty bombast. Just as taking the cross in 1215 had associated the young King Frederick with papal approval, and that of 1220 with joint

leadership of Christendom, so the vows of 1223 and 1225 marked stages of the development of a detailed crusade plan in response to acerbic criticism of his inaction during the Damietta campaign.