God's War: A New History of the Crusades (27 page)

Read God's War: A New History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Christopher Tyerman

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Military History, #European History, #Medieval Literature, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Religious History

The reunification of the combat armies reignited rivalries and feuding. Tancred of Lecce stirred up trouble by angling to desert Raymond’s service for that of Duke Godfrey, who now emerged as a powerful independent political force. Count Raymond, champion of the ordinary soldier only a few weeks before, appeared stubborn in his insistence on perpetuating what was now a strategically irrelevant siege rather than marching south. His loss of popular support was reflected in the trial and death in early April of Peter Bartholomew, now regarded as the count’s catspaw rather than the inspired voice of the people. A new series of reported visions pressed the case for an immediate attack on Jerusalem, Godfrey of Bouillon placing himself at the head of the popular agitation. Diplomatically, events clarified the crusaders’ options. A Greek embassy early in April led to weeks of wrangling over whether to delay an assault on Palestine by waiting for the promised arrival of the emperor. On 13 May, Godfrey broke up the siege of Arqah by moving towards Tripoli, taking with him many Provençals, ending the lingering pretence of a Byzantine alliance. At this moment, the ambassadors from Egypt returned with al-Afdal’s proposal for limited access to Jerusalem by unarmed Christians. While the westerners may have agreed to partition Palestine, leaving them control of the Holy City, this offer was impossible.

45

Original plans to liberate local Christians had long since been paralleled by the aim of acquisition, by conquest if necessary. It was later alleged that Urban II had offered this inducement at Clermont. Social and political reality in Syria and Palestine had revealed to the westerners that, with the fracturing of the Byzantine alliance, there was no fraternal Christian ruling class in church or state to whom the Holy Places could be entrusted. This subtle but profound shift from a war of liberation to one of occupation represented a portentous development in Urban II’s schemes, one forged by the experience of the campaign.

With Byzantine aid rejected, an Egyptian alliance refused, the army of God left Tripoli on 16 May 1099 with one aim in view: the seizure of Jerusalem in as short a time as possible, a race against time and an Egyptian counter-attack. With religious symbols prominently displayed,

the army reverted to type, the siege of Arqah, so far from consolidating Count Raymond’s command, provoking a reversion to collective leadership. Despite its fractious nature, the army made rapid progress, covering the 225 miles from Tripoli to Jerusalem in just twenty-three days. On the often narrow coast road, shadowed by the now dilapidated English fleet that had joined the expedition at Antioch a year earlier,

46

speed dictated a diplomatic approach to the cities the army passed. Treaties were negotiated with Beirut and Acre; Tyre, Haifa and Caesarea presented no opposition, while Sidon provided only minor resistance. Signalling their inability to organize a military response, the Fatimids dismantled and abandoned Jaffa, the port nearest Jerusalem. At Arsuf, the Christian army turned inland, capturing the evacuated town of Ramla on 3 June. After resting for a few days and leaving a bishop with a garrison at nearby Lydda, on 6 June the Christians, rejecting a suggestion, possibly from Count Raymond, to attack the Fatimids directly in Egypt, climbed up into the Judean hills towards Jerusalem, camping that night at Qubeiba, ten miles from the Holy City. That evening Tancred left the army to occupy the Christian town of Bethlehem, a few miles south of Jerusalem. Although one account describes the locals as initially unsure who these invaders were, fearing more Turks, the westerners were soon welcomed, Tancred’s diversion being a tribute to local intelligence and friendly contacts with co-religionists as much as to his own desire for dominion. Other elements from the army fanned out across the Judean hills, securing local villages and strongpoints. There was nothing quixotic about the march to Jerusalem. At Ramla voices had been raised warning of the dangers of besieging Jerusalem in high summer, chiefly lack of water. However, emotion and strategy compelled an immediate assault. The only hope of survival lay in capturing the city before the arrival of the Fatimid army. More than strategy drew the pilgrims on; one of them later recalled that in the final approach to the Holy City ‘a few who held God’s command dear marched along barefoot’; another summed up the general mood of the battered host at this climactic moment: ‘rejoicing and exulting’.

47

On Tuesday, 7 June the Christian army, numbering perhaps fewer than 14,000 fighting men, arrived at the walls of Jerusalem. The object of their quest reached, the ultimate trial began.

48

Given the threat of a Fatimid attack, the arid countryside, the impossibility of relief and the inability of such a small army to enforce a complete blockade, there was

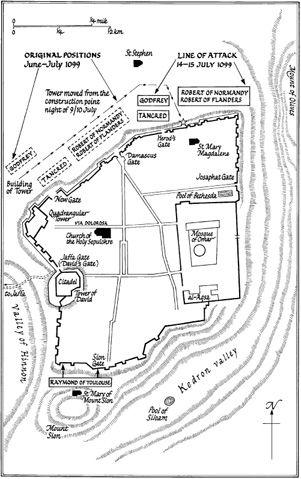

5. The Siege of Jerusalem, June–July 1099

no question of repeating the slow strangulation of Antioch. Prosecution of the siege was hampered by lack of water, necessitating elaborate schemes of water-carrying over large distances; illness, at least one of the leaders, Tancred, suffering from a bout of dysentery; the unavailability of sufficient wood for ladders, siege engines and towers; and a still divided command. While Godfrey, his new ally Tancred and the dukes of Normandy and Flanders maintained their separate camps outside the northern walls, Raymond of Toulouse initially established himself opposite the Citadel and the western walls before moving after a few days to blockade the Zion Gate in the south, almost as far removed from the northerners as possible. Thereafter, except for moments of communal ritual or planning the final assault, the two sections of the Christian army operated separately. A first, abortive attack on 13 June did not involve the Provençals at all. After the arrival of Genoese mariners who had put in at Jaffa on 17 June, with large timbers and skilled engineers, siege towers could be constructed, but each contingent made their own arrangements. Raymond, paying the construction artisans out of his own pocket, employed the Genoese William Ricau to build his tower, while the northerners, acting in concert, paid the workers out of a common fund, as at Antioch, and had Gaston of Béarn, himself a southerner from the Pyrenees, as their construction supervisor. Early in July, there were heated exchanges between the leaders over Tancred’s opportunistic claim to lordship over Bethlehem and the issue of the future rule of Jerusalem. Tancred and Raymond were formally reconciled only a week before the final assault. Bitterness was probably exacerbated by the defection to Godfrey of a number of prominent Provençals before or during the siege. In such circumstances, victory was little short of miraculous.

Behind the strong obstacles of double walls, moats and natural contours, the garrison facing the westerners, commanded by the Fatimid governor Iftikhar al-Dawla, was small and surprisingly passive. Made up of professional troops from Egypt and local militias, including troops from the Jewish community, it launched no disruptive forays and scarcely challenged the building of siege machines in the later stages of the investment. Its tactics appear to have been to await help, a policy encouraged by promises from al-Afdal which reached the city via the unguarded eastern side. The prospect of an Egyptian relief force thus forced one side to aggression, the other to inertia.

To capitalize on the surge of enthusiasm at having finally arrived at Jerusalem, on 13 June, allegedly at the promptings of a hermit living on the Mount of Olives, the northern leaders launched a speculative attack between the Quadrangular Tower in the north-west corner of the city and the Damascus Gate. Relying on only one ladder, even when the outer walls were breached, no concerted attack on the inner rampart was possible, the first man up, Raimbold Croton from Chartres, losing his hand in the attempt. Losses were heavy and, although the outer walls were damaged, the defences held. This failure persuaded the leaders, at a meeting two days later, that the next assault required more careful organization and the participation of all contingents. Over the next few weeks the region was scoured for supplies; the Genoese, with their vital timbers cannibalized from their ships, were escorted to the siege and the engineers set to work. As the material preparations reached fruition, it was agreed on

6

July to hold a solemn religious procession around the walls of the city, in imitation of Joshua at Jericho. The planning and execution of this morale-boosting ritual encapsulated the expedition’s spiritual history. The inspiration, some recalled, came from a vision received by Peter Desiderius; the decision to hold the procession was reached at an assembly summoned by William Hugh of Monteil, Adhemar of Le Puy’s brother. After a three-day fast, on 8 July the whole army, led by the clergy bearing the growing collection of relics, processed barefoot around the walls of Jerusalem, ignoring the taunts of the locals. On completion of the circuit, the host was addressed on the Mount of Olives by Raymond of Aguilers, for the Provençals, Arnulf of Choques, the smooth-talking chaplain to the duke of Normandy, and Peter the Hermit, now under the patronage of Godfrey of Bouillon and the Lorrainers. Count Raymond and Tancred were publicly reconciled.

49

The political and religious threads of the expedition were thus drawn tightly together in a public demonstration that recognized the regional diversity of the enterprise while insisting on its single identity, shared experience and common goal. As at Antioch, it was hoped that such rededication would ignite a willingness to hazard all in a last throw of fate. News of al-Afdal’s large relief army leaving Egypt had reached the Christian camp. It was now or never.

The final assault on Jerusalem begun on 13 July was a desperate affair. Attacks were launched on two fronts, by the Provençals on the narrow line of wall by the Zion Gate in the south and by the northern forces –

of Godfrey, Robert of Normandy, Robert of Flanders and Tancred – who had moved, with their siege tower and ram, to the north-east corner of the walls on 10 July. While the Provençals made little impact, the northerners’ slowly wore down the defence, their tactics revolving around pushing their siege tower as close to the inner wall as possible to allow troops to gain access to the ramparts by planks and ladders. While other contingents provided ferocious salvoes of arrows and bolts, the Lorrainers under Duke Godfrey were in charge of the tower. Resistance was everywhere fierce, strongest in the south, nearest to the centre of power at the Citadel; in both sectors catapults were used by the defenders. Casualties were high; perhaps as many as a fifth or a quarter of the western armies. Contact between the two Christian assaults was maintained by signallers stationed on the Mount of Olives using reflectors. At midday on Friday, 15 July, the dispirited Provençals were encouraged to renew their attack while the northerners’ siege tower was painfully edged towards the inner wall over which it towered. Albert of Aachen recorded that a golden cross was placed on the top storey of the tower, where Duke Godfrey himself stood firing his crossbow into the city.

50

When the tower was pushed right against the wall, from the storey below the brothers Ludolf and Engelbert from Tournai threw planks across the gap and entered the city, soon followed by Godfrey, Tancred and the Lorrainers. The defenders fled to the Haram al-Sharif, the Temple Mount, but were overtaken by Tancred before they could secure the precinct. The scale of the slaughter there impressed even hardened veterans of the campaign, who recalled the area ‘streaming with blood’ that reached to the killers’ ankles. Raymond of Aguilers resorted to the language of the Book of Revelation in describing the Christian knights in front of the al-Aqsa mosque wading through blood up to their horses’ knees.

51

The survivors took refuge inside the mosque, many hiding in the roof while Tancred plundered the Dome of the Rock near by before calling a halt to the killing by offering those inside the al-Aqsa mosque his protection, presumably hoping for ransom. Meanwhile, news of the entry of the Christians into the city caused the defenders in the south to withdraw to the Citadel, with Count Raymond in pursuit. Without delay Iftikhar al-Dawla struck a deal that guaranteed the garrison’s safe conduct to Ascalon in return for surrendering the Citadel, although some were ransomed, at knock-down rates.

52

The massacre in Jerusalem spared few. Jews were burnt inside their

synagogue. Muslims were indiscriminately cut to pieces, decapitated or slowly tortured by fire (this on Christian evidence). Such was the scale and horror of the carnage that one Jewish witness was reduced to noticing approvingly that at least the Christians did not rape their victims before killing them as Muslims did.

53

The city was comprehensively ransacked: gold, silver, horses, food, the domestic contents of houses, were seized by the conquerors in a pillage as thorough as any in the middle ages. Profit vied with destruction; some Jewish holy books were later ransomed to the surviving community in exile. Violence overcame business on 16 July when Tancred’s prisoners in the al-Aqsa mosque were butchered in cold blood, possibly by Provençals who had missed the previous day’s action. The city’s narrow streets were clogged with corpses and dismembered body parts, including some crusaders crushed in their zeal for the pursuit and massacre of the defenders. The heaps of the dead presented an immediate problem for the conquerors; on 17 July many of the surviving Muslim population were forced to clear the streets and carry the bodies outside the walls to be burnt in great pyres, whereat they themselves were massacred, a chilling pre-echo of later genocidal practices.