God's War: A New History of the Crusades (61 page)

Read God's War: A New History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Christopher Tyerman

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Military History, #European History, #Medieval Literature, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Religious History

Later Frankish sources favourable to Count Raymond recorded that, after Raymond had persuaded King Guy to adopt the same tactics as four years earlier and refuse battle, the Master of the Temple late at night managed to change the king’s mind. Some Muslim accounts agree that Raymond urged the abandonment of Tiberias, which, he hoped, would lead to the dispersal of Saladin’s army, eager to return home safely with their booty, only to be contradicted by Reynald of Châtillon, who reminded the king of Raymond’s recent treachery and alliance with the enemy. Saladin’s secretary, Imad al-Din, by contrast, portrayed Raymond as taking the lead in persuading Guy to march out to relieve Tiberias.

50

Whatever the immediate arguments and assessment of risks, Guy can hardly have avoided an unpleasant sense of

déjà vu

. In 1183, in similar circumstances, he had been vilified and hounded from office after failing to engage Saladin’s army even though he had kept the Frankish army intact and largely unscathed. Any advice he now received from political enemies, especially Raymond, must have appeared tainted. Aggression had served the Franks well in the past; Reynald of Châtillon was living proof of that. Sephoria lay just under twenty miles from Tiberias, just possible to reach in a day of forced march across the hilly terrain. If not, the substantial springs at Hattin, just over a dozen miles distant, offered refuge for a bivouac. The Frankish army was formidably large, with experienced leaders and seasoned troops. Despite the subsequent

verdicts of events, Guy’s decision during the night of 2–3 July to break camp and march to Tiberias may not then have appeared foolish or doomed. Two years later, when he led a tiny Christian army to begin the siege of Acre, an apparently far rasher decision led to ultimate success. However, in the Galilean hills in July 1187, once committed, Guy had no prospects of reinforcement and few of ordered retreat. His choice of battle consciously provoked a confrontation that would be decisive, whatever the outcome.

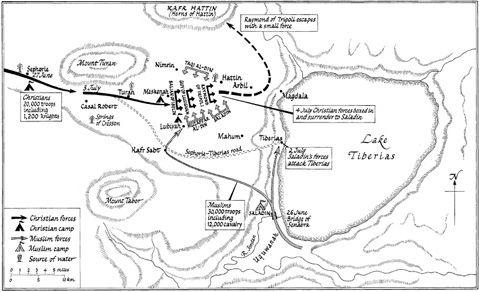

The Franks left Sephoria early on 3 July, heading towards the small spring at Turan about a third of the way to Tiberias. Progress was slow and before nightfall stopped altogether. Saladin broke off his siege of Tiberias and organized his army to meet the advancing Franks. Once the springs at Turan had been passed, the Franks found themselves attacked from the right flank and rear. The sheer weight of Muslim numbers slowed the Franks until they reached Maskana on the western edge of the plateau that looked down on the Sea of Galilee. Here the leadership once more seemed at odds, whether to attempt to force their way eastwards down from the plateau to Tiberias that night, or to turn aside northwards to the large wells at the village of Hattin. In the end, they did neither, Guy ordering a halt at Maskana. The decision to camp for the night on the arid plateau with little or no water may have come from confusion and hesitancy. But Guy may have had no option. Enemy numbers harrying the army had slowed progress almost to a standstill, preventing it from reaching the springs at Hattin and threatening to turn a descent to the Sea of Galilee into a massacre or rout. The Franks do not seem to have successfully reconnoitred the enemy’s strength. If they had known how heavily the odds were stacked against them, the decision at Sephoria may have been different.

By the morning of 4 July, the Franks found themselves surrounded. Their only, slim chance of success lay in pressing on towards the fresh water of the Sea of Galilee in the hope of manoeuvring the enemy into a position where a concerted cavalry charge could be mounted. The Frankish vanguard under Raymond of Tripoli made an early attempt to break the stranglehold, but the Muslims merely opened ranks, allowing the count and his followers to escape, an act that confirmed for many Raymond’s treachery. Completely encircled, constantly harassed by scrub fires and hails of arrows, the Franks avoided total disintegration by establishing themselves on the Horns of Hattin, where the remains

9. The Hattin Campaign, July 1187

of an extinct volcano surrounded by the ruins of Iron Age and Bronze Age walls offered some protection. Here both cavalry and infantry made their last stand. As in the similar circumstances when the Antiochene army had been surrounded at the Field of Blood in 1119 and Inab in 1149, the outcome could hardly have been in doubt. Yet, even

in extremis

, the Christian knights refused to submit. At some point, elements of the rearguard under Reynald of Sidon and Balian of Ibelin, who had borne the brunt of attacks throughout the previous day’s march, managed to break out through the Muslim lines. During the withdrawal to the Horns, a Templar attack failed to disturb the surrounding cordon though lack of support. At the end of the battle, fighting exhaustion and despair, King Guy led at least two charges from his fortified base directed against Saladin’s personal bodyguard, his final throw to reverse the impending defeat. It was later reported that these attacks, even from so desperate a position, alarmed the sultan.

51

Only when the remaining Frankish knights, having dismounted to defend the Horns on foot, were overwhelmed by thirst and fatigue as much as by their enemies, did the Muslims penetrate their final defences. Lack of water may have caused the collapse of horses as well as their riders, preventing further resistance. Guy and his knights were found slumped on the ground, unable to prolong the fight. Before these final moments, Frankish morale was destroyed by the capture of the relic of the True Cross and the death of its bearer, the bishop of Acre. This relic, discovered in the days after the capture of Jerusalem in July 1099, had regularly been carried into battle by the Jerusalem Franks as a totem of God’s support and promise of victory. Its loss, even more than the defeat itself, resonated throughout Christendom, raising the military disaster into a spiritual catastrophe.

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of the annihilation of the Frankish host was the numbers of survivors from the highest ranks of the nobility amid the carnage of thousands. Among the Frankish lords on their way to captivity Saladin had ushered to his tent after the battle were King Guy, his brother Aimery, Humphrey of Toron, Reynald of Châtillon, Gerard of Ridefort and old William of Montferrat, effectively most of the governing clique. By contrast, 200 captured rank and file Templars and Hospitallers were butchered amateurishly, almost ceremonially by Muslim Sufis, while infantry survivors were herded off to slave markets across the Levant. Alone of the grandest prisoners,

Reynald of Châtillon was executed, possibly by Saladin himself, after an elaborate charade in which the sultan expressly denied Reynald formal hospitality in the form of a drink that was offered round the other captives. The gesture was of revenge on an infidel aggressor who had dared to take war to the holy places of Arabia. The ritualistic manner of his killing as remembered by Saladin’s secretary, who was present, suggested this departure from normal practice followed the needs of propaganda rather than anger. Saladin was the most calculating of politicians. He needed a head. Reynald’s was the obvious victim. In western eyes, his death transformed this grizzled veteran of Outremer’s wars into a martyr whose fate was promenaded to encourage recruitment for the armies that hoped to reverse the decision of Hattin.

52

Meanwhile, before leaving the battlefield, Saladin ordered a dome to be constructed to celebrate his victory; its foundations survive to this day. Less permanent testimony to the great battle presented itself to the historian Ibn al-Athir, who crossed the battlefield in 1188. Despite the ravages of weather, wild animals and carrion birds, he ‘saw the land all covered with bones, which could be seen even from a distance, lying in heaps or scattered around.’

53

The completeness of Saladin’s victory was soon apparent. The army destroyed at Hattin had denuded the rest of the kingdom’s defences. Saladin’s progress was cautious but triumphal. Beginning with the surrender of Tiberias on 5 July and Acre on 10 July, he mopped up most of the ports within weeks, including Sidon (29 July) and Beirut (6 August). Tyre survived, and then only because of the arrival from the west of Conrad of Montferrat, son of the captured William and uncle to the dead Baldwin V, in mid-July. Most of the castles and cities of the interior fell, with the exception of the great fortresses of Montréal, Kerak, Belvoir, Saphet and Belfort. Northern Outremer awaited its turn. On 4 September 1187, Ascalon surrendered after a stiff fight, followed by the remaining strongholds in southern Palestine. After negotiations that had seen the sultan enhance his reputation for magnanimity by allowing the Queen Dowager Maria safe conduct from Jerusalem to Tyre, on 20 September Saladin invested the Holy City.

54

The garrison was commanded by Patriarch Heraclius, Balian of Ibelin, recently arrived from Tyre, and only two other knights. After a spirited show of resistance, and dramatic penances by the civilian population, the end came by negotiation. Saladin accepted payment for the release of most

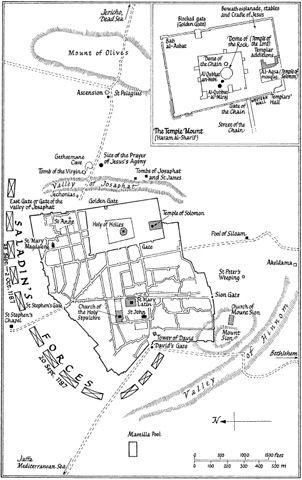

10. Saladin Captures Jerusalem, September–October 1187

of the besieged Christians, a contrast with the events of July 1099 that he was not slow to point out. Jerusalem opened its gates on 2 October. Saladin milked the symbolism of his triumph. The cross the Franks had erected on the Dome of the Rock was cast down; the al-Aqsa mosque was restored and Nur al-Din’s pulpit from Aleppo installed; the precincts of the Haram al Sharif purified, the sultan and his family playing a conspicuous role; prominent Frankish religious buildings, such as the house of the patriarch and the church of St Anne, were converted into Islamic seminaries or schools. On 9 October, Friday prayers were resumed in the al-Aqsa. The Holy Sepulchre was spared, some said out of a pragmatic understanding of the importance of the site not the building for Christian pilgrimage, from which in the future the sultan could profit. However, the Latin clergy were expelled. Saladin had fulfilled his titles not just as victorious king, al-Malik al-Nasir, but as Restorer of the World and Faith, Salah al-Dunya wa’l-Din. It was the pinnacle of his career.

News of Hattin reached the west by rumour, letter and messenger. While Saladin was gathering in the shattered remains of the kingdom, Joscius archbishop of Tyre set off to the west, arriving first in Sicily, where King William II immediately dispatched a fleet of about fifty ships with 200 knights.

55

The disaster produced profound shock. Pope Urban III reputedly died on hearing of it. Even before the full extent of Saladin’s conquests became known, a response began to be organized. In November 1187, Richard count of Poitou, eldest surviving son of Henry II of England, became the first ruler north of the Alps to take the cross.

56

In late October, the new pope, Gregory VIII, issued a bull,

Audita Tremendi

, authorizing a general expedition to the east and summarizing the privileges offered to those who took the cross. Gregory described the horrors of the battle of Hattin, ‘a great cause for mourning’, lingering over the Muslim atrocities and indicated the danger facing the Holy City itself; news of the fall of Jerusalem had not yet reached Italy. While laying most of the blame for the calamity on the sins of the Franks, the pope extended the burden of responsibility to include ‘the whole Christian people’. It was a Christian’s duty to repent past sins and restore past mistakes in the service of God and the recovery ‘of that land in which for our salvation truth arose from the earth’.

57

After forty years of complacency, indifference and lip-service, Christendom’s response to Gregory’s call was overwhelming.

12

The Call of the Cross

The response to the loss of Jerusalem and most of Outremer reinvented crusading. Central elements of later campaigns were introduced or confirmed: tightly organized preaching; crusade taxation, which allowed for more professional recruitment; transport by sea; and a widening strategic understanding of what was required to ensure the recovery of Jerusalem. Preachers and polemicists developed a sharper concentration on the flexible image of the cross, a banner of victory but also a badge of faith and sign of repentance. Extending the idea of communal penance contained in Gregory VIII’s bull

Audita Tremendi

, crusade publicists extrapolated the act of crusading into a clear general scheme of religious revivalism. This they associated with a firmer distinctive vocabulary of personal commitment mirrored in legally more explicit privileges of the crusader, the

crucesignatus

. Taking the cross now in theory clearly separated crusading from pilgrimage, even if surviving written liturgies and chroniclers retained the link. To the crusader’s special spiritual status coupled with the now customary privileges were joined precise and immediate secular benefits, such as exemption from the novel taxes levied to pay for the armies bound for the east. The experience of 1188–92 established in lay as well as ecclesiastical circles the technical name for participants in crusading even if it failed to discover an agreed term for the activity in which they were involved. Propagandists began to talk almost exclusively of ‘

crucesignati

’, a habit that soon found its way into chronicles, histories and government records. In the accounts of the English Exchequer,

crusiatus

appeared in 1188/9 and

crucesignatus

, for the first time, in 1191/2.

1

Vernacular equivalents, such as the verbs

croisier

and

croiser

, began to appear in the poems of departing crusaders and within a generation

croisié

had become common when describing a crusader.

2

While Jerusalem dominated the language of

preparation for the campaigns in the east, the failure of the Palestine war of 1191–2 to restore the Holy City to Christian rule produced a subtle but significant shift in linguistic focus that shadowed military reality. Thereafter the

iter Jerosolymitana

gave place to the broader inclusive euphemisms of

negotium Terrae Sanctae

or even simply the

negotium sanctum

, the business of the Holy Land, the holy business.