Going Solo (15 page)

Authors: Roald Dahl

I took off the next day from the bleak and sandy airfield of Abu Suweir, and after a couple of hours I was over Crete and beginning to get severe cramp in both legs. My main fuel tank was nearly empty so I pressed the little button that worked the pump to the extra tanks. The pump

worked. The main tank filled up again exactly as it was meant to and on I went.

After four hours and forty minutes in the air, I landed at last on Elevsis aerodrome, near Athens, but by then I was so knotted up with terrible excruciating cramp in the legs I had to be lifted out of the cockpit by two strong men. But I had come home to my squadron at last.

So this was Greece. And what a different place from the hot and sandy Egypt I had left behind me some five hours before. Over here it was springtime and the sky a milky-blue and the air just pleasantly warm. A gentle breeze was blowing in from the sea beyond Piraeus and when I turned my head and looked inland I saw only a couple of miles away a range of massive craggy mountains as bare as bones. The aerodrome I had landed on was no more than a grassy field and wild flowers were blossoming blue and yellow and red in their millions all around me.

The two airmen who had helped to lift my cramped body out of the cockpit of the Hurricane had been most sympathetic. I leant against the wing of the plane and waited for the cramp to go out of my legs.

‘A bit scrunched up in there, were you?’ one of the airmen said.

‘A bit,’ I said. ‘Yes.’

‘You oughtn’t to be flyin’ fighters a chap of your height,’ he said. ‘What you want is a ruddy great bomber where you can stretch your legs out.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘You’re right.’

This airman was a Corporal. He had taken my parachute out of the cockpit and now he brought it over and placed it on the ground beside me. He stayed with me and it was clear that he wanted to do some more talking.

‘I don’t see the point of it,’ he went on. ‘You bring a brand-new kite, an

absolutely spanking brand-new kite

straight from the factory and you bring it all the way from ruddy Egypt to this godforsaken place and what’s goin’ to ’appen to it?’

‘What?’ I said.

‘It’s come even

further

than from Egypt!’ he cried. ‘It’s come all the way from

England

, that’s where it’s come from! It’s come all the way from England to Egypt and then all the way across the Med to this soddin’ country and all for what? What’s goin’ to ’appen to it?’

‘What

is

going to happen to it?’ I asked him. I was a bit taken aback by this sudden outburst.

‘I’ll tell you what’s goin’ to ’appen to it,’ the Corporal said, working himself up. ‘Crash bang wallop! Shot down in flames! Explodin’ in the air! Ground-strafed by the One-O-Nines right ’ere where we’re standin’ this very moment! Why, this kite won’t last one week in this place! None of ’em do!’

‘Don’t say that,’ I told him.

‘I ’as to say it,’ he said, ‘because it’s the truth.’

‘But why such prophecies of doom?’ I asked him. ‘Who is going to do this to us?’

‘The Krauts, of course!’ he cried. ‘Krauts is

pourin’

in ’ere like ruddy ants! They’ve got

one thousand planes

just the other side of those mountains there and what’ve

we

got?’

‘All right then,’ I said. ‘What

have

we got?’ I was interested to find out.

‘It’s pitiful what we’ve got,’ the Corporal said.

‘Tell me,’ I said.

‘What we’ve got is exactly what you can see on this

ruddy field!’ he said. ‘

Fourteen ’urricanes

! No it isn’t. It’s gone up to fifteen now you’ve brought this one out!’

I refused to believe him. Surely it wasn’t possible that fifteen Hurricanes were all we had left in the whole of Greece.

‘Are you absolutely sure of this?’ I asked him, aghast.

‘Am I lyin’?’ he said, turning to the second airman. ‘Please tell this officer whether I am lyin’ or whether it’s the truth.’

‘It’s the gospel truth,’ the second airman said.

‘What about bombers?’ I said.

‘There’s about four clapped-out Blenheims over there at Menidi,’ the Corporal said, ‘and that’s the lot.

Four Blenheims and fifteen ’urricanes

is the entire ruddy RAF in the ’ole of Greece.’

‘Good Lord,’ I said.

‘Give it another week,’ he went on, ‘and every one of us’ll be pushed into the sea and swimmin’ for ’ome!’

‘I hope you’re wrong.’

‘There’s five ’undred Kraut fighters and five ’undred Kraut bombers just around the corner,’ he went on, ‘and what’ve we got to put up against them? We’ve got a miserable fifteen ’urricanes and I’m mighty glad I’m not the one that’s flyin’ ’em! If you’d ’ad any sense at all, matey, you’d’ve stayed right where you were back in old Egypt.’

I could see he was nervous and I couldn’t blame him. The ground-crew in a squadron, the fitters and riggers, were virtually non-combatants. They were never meant to be in the front line and because of that they were unarmed and had never been taught how to fight or defend themselves. In a situation like this, it was easier to be a pilot

than one of the ground-crew. The chances of survival might be a good deal slimmer for the pilot, but he had a splendid weapon to fight with.

The Corporal, as I could tell by the grease on his hands, was a fitter. His job was to look after the big Rolls-Royce Merlin engines in the Hurricanes and there was little doubt that he loved them dearly. ‘This is a brand-new kite,’ he said, laying a greasy hand on the metal wing and stroking it gently. ‘It’s took somebody

thousands of hours

to build it. And now those silly sods behind their desks back in Cairo ’ave sent it out ’ere where it ain’t goin’ to last two minutes.’

‘Where’s the Ops Room?’ I asked him.

He pointed to a small wooden hut on the other side of the landing field. Alongside the hut there was a cluster

of about thirty tents. I slung my parachute over my shoulder and started to make my way across the field to the hut.

To some extent I was aware of the military mess I had flown in to. I knew that a small British Expeditionary Force, backed up by an equally small air force, had been sent to Greece from Egypt a few months earlier to hold back the Italian invaders, and so long as it was only the Italians they were up against, they had been able to cope. But once the Germans decided to take over, the situation immediately became hopeless. The problem confronting the British now was how to extricate their army from Greece before all the troops were either killed or captured. It was Dunkirk all over again. But it was not receiving the publicity that Dunkirk had received because it was a military bloomer that was best covered up. I guessed that everything the Corporal had just told me was more or less true, but curiously enough none of it worried me in the slightest. I was young enough and starry-eyed enough to look upon this Grecian escapade as nothing more than a grand adventure. The thought that I might never get out of the country alive didn’t occur to me. It should have done, and looking back on it now I am surprised that it didn’t. Had I paused for a moment and calculated the odds against survival, I would have found that they were about fifty to one and that’s enough to give anyone the shakes.

I pushed open the door of the Ops Room hut and went in. There were three men in there, the Squadron-Leader himself and a Flight-Lieutenant and a wireless-operator Sergeant with ear-phones on. I had never met any of them before. Officially, I had been a member of 80 Squadron

for more than six months, but up until now I had not succeeded in getting anywhere near it. The last time I had tried, I had finished up on a bonfire in the Western Desert. The Squadron-Leader had a black moustache and a Distinguished Flying Cross ribbon on his chest. He also had a frowning worried look on his face. ‘Oh, hello,’ he said. ‘We’ve been expecting you for some time.’

‘I’m sorry I’m late,’ I said.

‘Six months late,’ he said. ‘You can find yourself a bunk in one of the tents. You’ll start flying tomorrow like the rest of them.’

I could see that the man was preoccupied and wished to get rid of me, but I hesitated. It was quite a shock to be dismissed as casually as this. It had been a truly great struggle for me to get back on my feet and join the squadron at last, and I had expected at least a brief ‘I’m glad you made it,’ or ‘I hope you’re feeling better.’ But this, as I suddenly realized, was a different ball game altogether. This was a place where pilots were disappearing like flies. What difference did an extra one make when you only had fourteen? None whatsoever. What the Squadron-Leader wanted was

a hundred

extra planes and pilots, not one.

I went out of the Ops Rooms hut still carrying my parachute over my shoulder. In the other hand I carried a brown paper-bag that contained all the belongings I had been able to bring with me, a toothbrush, a half-finished tube of toothpaste, a razor, a tube of shaving soap, a spare khaki shirt, a blue cardigan, a pair of pyjamas, my Log Book and my beloved camera. Ever since I was fourteen I had been an enthusiastic photographer, starting in 1930 with an old double-extension plate camera and doing my

own developing and enlarging. Now I had a Zeiss Super Ikonta with an f 6.3 Tessar lens.

Out in the Middle East, both in Egypt and in Greece, unless it was winter we dressed in nothing but a khaki shirt and khaki shorts and stockings, and even when we flew we seldom bothered to put on a sweater. The paper-bag I was now carrying, as well as the Log Book and the camera, had been tucked under my legs on the flight over and there had been no room for anything else.

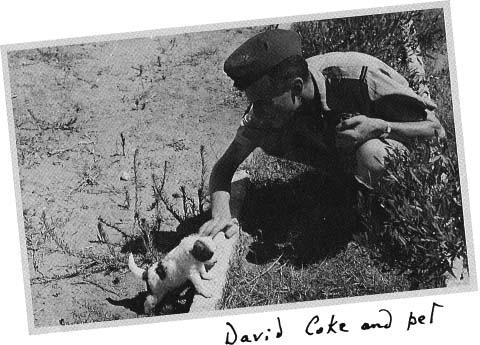

I was to share a tent with another pilot and when I ducked my head low and went in, my companion was sitting on his camp-bed and threading a piece of string into one of his shoes because the shoe-lace had broken. He had a long but friendly face and he introduced himself as David Coke, pronounced Cook. I learnt much later that David Coke came from a very noble family, and today, had he not been killed in his Hurricane later on, he would have been none other than the Earl of Leicester owning one of the most enormous and beautiful stately homes in England, although anyone acting less like a future Earl I have never met. He was warm-hearted and brave and generous, and over the next few weeks we were to become close friends. I sat down on my own camp-bed and began to ask him a few questions.

‘Are things out here really as dicey as I’ve been told?’ I asked him.

‘It’s absolutely hopeless,’ he said, ‘but we’re plugging on. The German fighters will be within range of us any moment now, and then we’ll be outnumbered by about fifty to one. If they don’t get us in the air, they’ll wipe us out on the ground.’

‘Look,’ I said, ‘I have never been in action in my life. I haven’t the foggiest idea what to do if I meet one of them.’

David Coke stared at me as though he were seeing a ghost. He could hardly have looked more startled if I had suddenly announced that I had never been up in an aeroplane before. ‘You don’t mean to say’, he gasped, ‘that you’ve come out to this place of all places with absolutely no experience whatsoever!’

‘I’m afraid so,’ I said. ‘But I expect they’ll put me to fly with one of the old hands who’ll show me the ropes.’

‘You’re going to be unlucky,’ he said. ‘Out here we go up in ones. It hasn’t occurred to them that it’s better to fly in pairs. I’m afraid you’ll be all on your own right from the

start. But seriously, have you never even been in a squadron before in your life?’

‘Never,’ I said.

‘Does the CO know this?’ he asked me.

‘I don’t expect he’s stopped to think about it,’ I said. ‘He simply told me I’d start flying tomorrow like all the others.’

‘But where on earth have you come from then?’ he asked. ‘They’d never send a totally inexperienced pilot to a place like this.’

I told him briefly what had been happening to me over the last six months.

‘Oh Christ!’ he said. ‘What a place to start! How many hours do you have on Hurricanes?’

‘About seven,’ I said.

‘Oh, my God!’ he cried. ‘That means you hardly know how to fly the thing!’

‘I don’t really,’ I said. ‘I can do take-offs and landings but I’ve never exactly tried throwing it around in the air.’