Goodbye, Darkness (23 page)

We made two more feeble attempts. If we had been physically compatible, I think I would have rolled us off the mattress and chanced the glass, the mousetraps, and whatever else lurked below. But it was useless. My strength was ebbing. By the time I grappled with my skivvies and khakis, I was not only frustrated, I was also suffering from motion sickness. I rolled off the levitating mattress and left Mae sprawled across the litter below, snoring and belching. The bottle was almost empty. I wanted to break it over either her head or the bedstead. But I was too tired, and too sore with lover's nuts, for either. Instead, I stumbled downstairs, found a pay phone, and called a taxi. Sexwise, my score was still zero to zero. And after paying the cabbie for the long trip, I was broke again. I couldn't even afford a tip. The driver was surly. I was surlier.

Nine hours later I led my section aboard the APA

Morton

, into a compartment below the waterline which would be our pent home throughout the seventeen-day voyage to Guadalcanal. Two light meals would be served each day; we would have to bolt each down, while standing, in a maximum of three minutes. We could expect to grow filthier each day; the only showers would be saltwater showers. We couldn't exercise — there was no room — or, for security reasons, remain on deck, where we might catch a breeze, after darkness. Already, as the winches shrieked and the transport built a welter of water beneath her hull, we were encountering one of the miseries of life on a transport: the deafening sound of the PA system, the blast of “The smoking lamp is out. Now sweepers, man your brooms! A clean sweep-down, fore and aft!”

But my thoughts were elsewhere just then. I wasn't thinking of Mae, or Taffy; not even of my mother. I was trying to make peace with my very personal, existential, Augustan faith, remembering Psalm 107, about men that go down to the sea in ships. Most fighting men cannot imagine their own deaths. All those I knew on that ship were confident that they would see America again. I wasn't; I had no premonition, but I knew the odds and was uncomforted by them. In any event, my destiny was nonnegotiable. I stood on the fantail, watching the California coastline recede as the

Morton

and the rest of the convoy began zigzagging to evade submarines. I was aware, and depressed by the knowledge, that this was probably my farewell to the United States. I hoped I would fight well. I felt ready; I felt that my men were ready. Then I made my way to the other end of the ship and peered westward across the gray expanse of water, superficially like my Atlantic but immeasurably larger and more vivid. Its name, considering the role it was about to play in our lives, was the ultimate irony. It was called Pacific.

The Canal

M

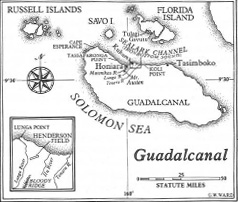

y first impression of guadalcanal is somewhat blurred, be-

cause I began by looking in the wrong direction. The great battle was over — a source of disappointment to some, and, to me, of inexpressible joy — but we were proceeding with the combat landing drill just the same. Buckling on my chamberpot helmet that hot August morning, saddling up so my pack straps brought the padding to the exact place where the straps joined on the tops of my shoulders, I peered westward across a cobalt sea dancing with incandescent sunlight and saw a volcanic isle which looked as ominous as the hidden fire in its belly. It didn't bear the slightest resemblance to what we had been told to expect. Casually flipping my hands to my hips and sauntering to the rail, I smoothed the wrinkles out of my voice and said in my deepest, manliest, trust-the-Sarge manner: “So that's it. They gave us bad dope, as usual.” Someone touched my forearm. It was little Pip Spencer, the chick of the outfit. He said: “It's on the other side, Slim.” I had been looking at Savo Island. I turned southward, disconcerted, having lost face even before we boarded the Higgins boats — those landing craft with hinged ramps built in New Orleans by the flamboyant Andrew Jackson Higgins — and beheld a spectacle of utter splendor.

In the dazzling sunshine a breeze off the water stirred the distant fronds of coconut palms. The palm trees stood near the surf line in precise, orderly groves, as though they had been deliberately planted that way, which, we later learned, was the case; we were looking at plantations owned by Lever Brothers. (Their stockholders were following the course of the Pacific war with great interest. Later the Allies settled nearly seven million dollars in damage claims. The Japanese, of course, paid nothing.) On the far horizon lay dun-colored foothills, dominated by hazy blue seven-thousand-foot mountains. Between the palms and the foothills lay the hogback ridges and the dense green mass of the Canal. Our eyes were riveted on it. We were seeing, most of us for the first time, real jungle.

I thought of Baudelaire:

fleurs du mal

. It was a vision of beauty, but of evil beauty. Except for occasional patches of shoulder-high kunai grass, the blades of which could lay a man's hand open as quickly as a scalpel, the tropical forest swathed the island. From the APA's deck it looked solid enough to walk on. In reality the ground — if you could find it — lay a hundred feet below the cloying beauty of the treetops, the cathedrals of banyans, ipils, and eucalyptus. In between were thick, steamy, matted, almost impenetrable screens of cassia, liana vines, and twisted creepers, masked here and there by mangrove swamps and clumps of bamboo. It was like New Guinea, except that on Papua the troops at least had the Kokoda Trail. Here the green fastness was broken only by streams veining the forest, flowing northward into the sea. The forest seemed almost faunal: arrogant, malevolent, cruel; a great toadlike beast, squatting back, thrusting its green paws through ravines toward the shore, sulkily waiting to lunge when we were within reach, meanwhile emitting faint whiffs of foul breath, a vile stench of rotting undergrowth and stink lilies. Actually, we had been told in our briefings, there were plenty of real creatures awaiting us: serpents, crocodiles, centipedes which could crawl across the flesh leaving a trail of swollen skin, land crabs which would scuttle in the night making noises indistinguishable from those of an infiltrating Jap, scorpions, lizards, tree leeches, cockatoos that screamed like the leader of a banzai charge, wasps as long as your finger and spiders as large as your fist, and mosquitoes, mosquitoes, mosquitoes, all carriers of malaria. If wounded, you had been warned, you should avoid the sea. Sharks lurked there; they were always hungry. It was this sort of thing which had inspired some anonymous lyricist among the 19,102 Marines in the first convoy to compose the lugubrious ballad beginning, “Say a prayer for your pal on Guadalcanal.”

On the nineteen transports in the original force the Marine infantry had been subdued, and not just because of the air of foreboding gloom which spread like a dark olive stain over the entire island. Down below in the holds enlisted men had been quiet, though awake, writing letters, sharpening bayonets, blackening the sights of rifles and carbines, checking machine-gun belts to make certain they wouldn't jam in the Brownings, rummaging in packs to be sure they had C rations. They carried canteens, Kabar knives, and first-aid kits hooked to web belts; packs of cigarettes, Zippo lighters, shaving gear, skivvies, mess kits, shelter halves, ponchos, two extra bandoliers of ammunition for each man, clean socks, and, hanging from straps and web belts like ripe fruit waiting to be plucked, hand grenades. Some were literally whistling in the dark (“My momma done tole me …”) or just milling around in the companionways. There wasn't much room to mill. Around the heads people were almost wedged against each other, a few inches from sodomy. There was no place to sit. Tiered in fives, and, where the overhead was higher, in sixes, the bunks were cluttered with helmets, helmet liners, knapsacks, pick and shovel entrenching tools, and 782 gear. During the long hours of waiting, the tension and frustration became almost unbearable. There was a myth, then and throughout the war, that this had been planned, that the Marine Corps wanted us infuriated when we hit the beach. But the Corps wasn't that subtle. And the men needed no goading. Morale was sky-high, reminiscent of Siegfried Sassoon's account of British esprit the week before the Battle of the Somme in 1916: “there was harmony in our company mess, as if the certainty of a volcanic future put an end to the occasional squabblings which occurred when we were on one another's nerves. A rank animal healthiness pervaded our existence during those days of busy living and inward foreboding. … Death would be lying in wait for the troops next week, and now the flavor of life was doubly strong. … I was trying to convert the idea of death in battle into an emotional experience. Courage, I argued, is a beautiful thing, and next week's attack is what I have been waiting for since I joined the army.” If you were a green Marine fresh from civilian life, waiting to race ashore on Guadalcanal, vitality surged through you like a powerful drug, even though the idea of death held no attraction for you. Your mood was an olla podrida, a mélange of apprehension, cowardice, curiosity, and envy — soon to be discredited by events — of the safe, dry sailors who would remain on board.

The bluejackets who would come closest to your destination were the coxswains of the Higgins boats. At the signal “Land the Landing Force,” their little craft, absurdly small beside the transport, bobbed up and down as you climbed down the cargo nets hanging over the APA's side. Descent was tricky. Jap infantrymen carried 60 pounds. A Marine in an amphibious assault was a beast of burden. He shouldered, on the average, 84.3 pounds, which made him the most heavily laden foot soldier in the history of warfare. Some men carried much more: 20-pound BARs, 45-pound 81-millimeter-mortar base plates, 47-pound mortar bipods, 36-pound light machine guns, 41-pound heavy machine guns, and heavy machine-gun tripods, over 53 pounds. A man thus encumbered was expected to swing down the ropes like Tarzan. It was a dangerous business; anyone who lost his grip and fell clanking between the ship and the landing craft went straight to the bottom of Sealark Channel, and this happened to some. More frequent were misjudgments in jumping from the cargo net to the boat. The great thing was to time your leap so that you landed at the height of the boat's bob. If you miscalculated, the most skillful coxswain couldn't help you. You were walloped, possibly knocked out, possibly crippled, when you hit his deck.

Judged by later standards, the Guadalcanal landing of August 7, 1942 — America's first offensive of the war, encoded “CACTUS” — was primitive. Amphibious techniques were in their infancy. The Marine Corps lacked essential information on tide, terrain, and weather. There were no reliable maps, no LSTs, and no DUKWs, those amphibian tractors, or boats with wheels, which were then still in the experimental stage. The heyday of underwater demolition teams lay ahead. World War I weapons were standard because the Corps, though part of the navy, used army equipment and didn't get new issue until the last GI got his. One curious weapon, which we came to loathe, was a machine pistol called the Reising gun; it rusted quickly, jammed at the slightest provocation, and was quite useless in the jungle. The twin-purpose entrenching tool hadn't reached the Pacific yet. Again, men were carrying 1918 relics: even-numbered men had little picks and odd-numbered men little shovels; once ashore, they dug in together. The Higgins boats were crude prototypes, and on shore-to-shore operations they were towed by “Yippies,” or YP (yard patrol) craft, wide, smelly speed-boats which emitted deafening chug-chugs and clouds of sparks, making stealth impossible. The landing force's chief job was to complete and use the unmatted twenty-six-hundred-foot airstrip the Japanese had already started, but there were shortages of cement, valves, pipes, pumps, prefabricated steel sections for fuel storage tanks, Marsden runway matting, and earth-moving machinery. (There was one small bulldozer. Only the operator was allowed to touch it. Under a standing order, anyone else approaching it was to be shot.)

But the basic attack concept, shelling a beach and then sending in waves of infantry, had been established. Marines were grouped thirty-six men to a boat. The boats for each wave formed a ring, circling until they fanned out in a broad line and sped the wave shoreward. Aboard, you crouched beneath the gunwales, seasick, struggling to keep from vomiting. There was no Dramamine then. Most men compared the seasickness to that on a terrible roller coaster ride, Mae's Murphy bed raised to the nth degree. Coxswains in later operations learned to give their wretched human cargo smoother rides, but none improved on the precise timing that August morning at the Canal. Zero hour had been set for 9:10

A.M.

At 9:09 the first wave splashed ashore toward the quiet, shell-shredded palms on Red Beach, four miles east of the Lunga River. Lacking opposition, two battalions of the Fifth Marines, my father's old regiment, swiftly established a two-thousand-yard-wide beachhead.