Goodbye, Darkness (30 page)

The following morning I call on Captain H. Honda in his office at the Taiko Fisheries Company. He is younger than I am, and looks younger still, a short, slender, but sinewy man with neatly parted black hair and eyes like green marbles. But he was old enough to volunteer for the kamikaze corps in 1945. He was turned down, and I, hoping to find common ground, congratulate him on his failure to pass the kamikaze examination. It doesn't work. His smile is so thin that he stops just short of baring his teeth. And to my surprise, after all these years I find my own hackles rising. The sad truth is that there can never be peace between men like this man and men like me; an invisible wall will forever separate us. To make the interview as short as possible, I confine myself to one bland question, asking whether he thinks that the new Solomons nation can become economically independent. He shakes his head. Papua, yes; the Fijis, yes; the Solomons, no. The problem, he says, is oriental imperialism. Bougainville, the richest of the islands, has been annexed by the Papuans. But the Papuans are victims, too; West Irian, the western half of their island, has been seized by the Indonesians. These issues have never been raised in the United Nations. Imperialism, it seems, is a crime in the UN only when the imperialists are white.

Returning to my hotel, I pass the local movie theater, a converted Quonset hut — the current flick is “It Happened One Night” — and meet Bill Bennett, an old coastwatcher wearing a First Raider Battalion T-shirt. Bennett and another Australian at the bar don't share Honda's pessimism, though they warn me not to be fooled by Honiara's fashion shops and the current island craze for Adidas footwear. Outside the city, Guadalcanal is still primitive. Although there is electricity here in the town, elsewhere, save for a few generators, light is provided by kerosene lamps. To be sure, the Seventh-Day Adventists have built a high school, Planned Parenthood has established a lively chapter, and the local hospital — still called Hospital No. 9, as it was in 1942, for sentimental reasons — is first class. But the government is weak and few islanders are interested in, or even aware of, their independence. “Oh, yes,” says Bill's friend. “I forgot to mention that before leaving the British built a mental hospital.” I say, “We could have used it.”

My tour of the island convinces me that the Canal is still essentially pristine. On Red Beach I find the remains of a floating pier and two amphibian tractors, overgrown by vines and covered with nearly four decades of rust. Otherwise the fine-grained gray beach and the stately palms are much as they were on August 7, 1942. At Henderson Field the black skeleton of the old control tower is untouched. Cassia grows in a half-track near the airstrip. Since the field is now surfaced with concrete, natives have liberated strips of Marsden matting and use them for fences. To the west are the Japanese shrines — they are the same, I shall find, on all the islands: six feet high, four sided, with Japanese characters on all sides. I also discover several U.S. Army markers, but almost none erected by the Marine Corps. Here and there one comes across the fuselage of a downed World War II plane; invariably the interiors reek of urine. Near the Kokumbona River I trace the contours of old trenches and foxholes wrinkling the ground, though my own elude me. Except on the Ridge and the Ilu sandspit, all other landmarks of the past, including the Jap Bridge, have been reclaimed by the jungle. This is even true at Hell's Point, a stockpile of unexploded ammunition still marked out-of-bounds for anyone straying near it. There are overgrown Hell's Points all over the Pacific; they are the war's chief legacy to natives. I point to the warning sign, nearly obscured by vines, and tell Koria that this is a barren wasteland, that is will always be dangerous. He nods grimly and replies, “Mi save gut”: he understands it well.

After the Allied victories on Papua and Guadalcanal, Japan's great 1942 offensive spluttered and died. In Tokyo Hirohito's generals and admirals assured him that they could hold the empire they had won. Until now American strategists in Washington had tacitly agreed; their plans for the Pacific war had been defensive; they had wanted only to hold Australia and Hawaii until the war in Europe had been won. But MacArthur, Halsey, and Nimitz were aggressive commanders. They had shown what their troops could do. In the southwest Pacific they were determined to seize, or at least neutralize, Rabaul. MacArthur could then skip along New Guinea's northern coast, moving closer to his cherished goal, the recapture of the Philippine Islands. And the U.S. Navy could open another offensive in the central Pacific. The split command worried the Joint Chiefs, and to this day historians wonder whether it was wise. MacArthur wasn't interested in the central Pacific, while Admiral King was convinced that Japan could be defeated without an American reconquest of the Philippines.

Actually the two drives became mutually supporting, each of them protecting the other's flank. Nimitz, King's theater commander, diverted enemy sea power which would otherwise have pounced on MacArthur from the east, while MacArthur's air force took out enemy planes which could have driven the Marines from their island beachheads. Their strategies differed — MacArthur's was to move land-based bombers forward in successive bounds to achieve local air superiority, while Nimitz's was predicated on carrier air power shielding amphibious landings on key isles, which then became stepping-stones through the enemy's defensive perimeters — but that was because they were dealing with different landscapes and seascapes. For a man in his sixties, MacArthur was extraordinarily receptive to new military concepts. Not only could he adopt the amphibious techniques developed by the Marine Corps; he went one step further by waging what Churchill later called “

tri

phibious warfare”— the coordination of land, sea, and air forces. At West Point the general had been taught army doctrine: rivers are barriers. At Annapolis, midshipmen are told that bodies of water are highways. MacArthur combined the two brilliantly.

His GIs never liked him, of course. He was too egotistical, they thought, and too unappreciative of them. He was that and more — perhaps the most exasperating general ever to wear a uniform. But his genius quickened the war, foiled the enemy, and executed movements beyond the imagination of the less gifted soldiers who scorned him.

Perhaps his two most famous battles were fought at Hollandia, now the Indonesian capital of Djajapura, and the island of Biak, between New Guinea and the Philippines. You can reach Djajapura's Senatai Airport on a weekly Air Niugini flight from Port Moresby; daily DC-9 flights leave Senatai for Biak. Hollandia, as those who served there know, has one of the world's finest natural harbors. Wartime warehouses and Quonset huts can still be found along the water, but most of the city's buildings date from the 1950s. Between Senatai and Cendrawasih University and the northwestern edge of the bay a large cement memorial marks the site of MacArthur's headquarters. Senatai is one of the Pacific's few international airports, but shipping in the harbor is scarce, and the government does not encourage visitors. Except for missionaries and an occasional businessman or tourist, one rarely sees a white face. The population is roughly half Indonesian and half Irianese. The fashionable suburb on Angkasa Hill offers a superb view of the harbor, and the governor's new office building (

Gubernuran

) is handsome. Otherwise, Hollandia is a disappointment. The city itself is built around a market and a central plaza. You find a couple of movie theaters there and a shocking stench of fish, garbage, and dog excrement.

Biak is more interesting. It, too, has its forlorn sights, notably railroad tracks which emerge from the bush, cross a crumbling dock, and vanish into the sea, but wartime memorabilia are easy to find. You arrive at Mokmer Airfield, the only one of MacArthur's huge runways there which still exists. Across from the field stands the old Bachelor Officers' Quarters, now a hotel run by the Merpati Nusantara Airways. And north of there you can explore what the natives call the “Japanese Caves” area — a complex of natural caverns in which Colonel Naoyuki Kuzumi holed up with his men for their last stand in June of 1944. When they refused to surrender, GIs dynamited the roof of the main cave. The roof collapsed, killing the defenders, and you can peer down at the debris of defeat: canteens, ammunition boxes, bits of uniforms, rifles, and the rusting skeletons of Jap vehicles.

Biak was a key battle, because Kuzumi had made the most murderous discovery of the war. Until then the Japs had defended each island at the beach. When the beach was lost, the island was lost; surviving Nips formed for a banzai charge, dying for the emperor at the muzzles of our guns while few, if any, Americans were lost. After Biak the enemy withdrew to deep caverns. Rooting them out became a bloody business which reached its ultimate horrors in the last months of the war. You think of the lives which would have been lost in an invasion of Japan's home islands — a staggering number of American lives but millions more of Japanese — and you thank God for the atomic bomb.

Back on Guadalcanal, I leave on an early morning call. Bob Milne, a local pilot, has invited me to fly up the Slot tomorrow in his little twin-engine, orange-and-white Queenair DC-3. In 1943, when MacArthur slowly approached the Philippines, we were inching up the ladder of the Solomons. Today we can fly to Bougainville and back in a day, but over a year passed between the Bloody Ridge battle and the Third Marine Division's landing at Bougainville's Empress Augusta Bay. In between we had driven the enemy from the islands of Pavuvu, Rendova, New Georgia, Vella Lavella, Kolombangara, Choiseul, Mono, and Shortland. This was Halsey's job. He was one of the few admirals who could work in tandem with MacArthur; between them they isolated the great Jap stronghold at Rabaul, where over 100,000 of Hirohito's infantrymen, who asked only to die for their emperor, were bypassed and left to bitterness and frustration. After the conquest of the Slot the Pacific war was divided into its two great theaters, MacArthur's and Nimitz's.

At daybreak Bob races us across Henderson's concrete and we soar over the Matanikau, Honiara, and Cape Esperance. Presently Santa Isabel looms to starboard and then New Georgia to port. Peering down from my copilot's seat I see the islands on either side of the Slot as huge, green, hairy mushrooms dominated by volcanic mountains, of which 8,028—foot Pobomanashi is the highest. Here and there a clump of thatched roofs marks the site of a village, but these are few; in this part of the world there are more islands than people. As we lose altitude in the shining morning air, Bob points at crocodiles dozing in the sun and then toward Lolo, the largest lagoon in the world, over sixty-eight miles long. Rising once more, we pass over an enormous coconut plantation and then over more familiar terrain: hummocks of ascending hills with valleys, alternately jungle and kunai grass. On the dim horizon I spot Bougainville, that large, mountainous island of spectacular volcanoes and trackless rainforests where bulldozers can, and did, sink in the green porridge of swampland without leaving a trace.

Nothing historic is happening here now. The islands haven't changed since a million men altered the course of the war in countless local engagements. Bob points down at the remains of one of them, a shadow beneath the water which, he tells me, is the sunken hull of John F. Kennedy's PT-109. Once these skies belonged to Pappy Boyington. Now we refuel at a base Boyington used, Munda, on New Georgia, bulldozed and surfaced by Seabees long ago and now a carpet of weed-splotched coral. At Kieta, our turnabout field — this is on Bougainville, under the Papuan flag — I stretch my legs and drink 7-Up in a tiny tin-roofed terminal building which the Australians erected in 1970. It is modest, even shabby: linoleum on the floor, a figured-calico-covered table, broken wicker chairs. Like most airports in this part of the world it is usually crowded, mostly with natives there to see friends off or welcome them back. Some of them stare at me. One tells me in pidgin that Caucasians are rare here — so rare in the hills inland that when one of them appears the native girls open their thighs for him out of gratitude for the comic relief.

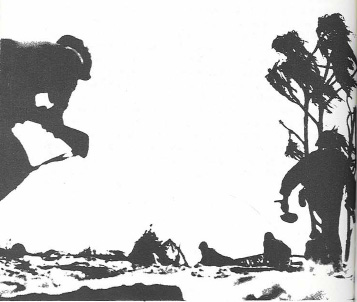

Elsewhere, in the Palaus and Marianas, ecology is shaping up as a public issue. Not in the Solomons; one doubts that it can ever be raised here. The jungle, allied with the climate, seems too strong ever to be threatened by man. The war was a major assault on the rainforests. It is scarcely remembered now. Nature holds all the cards. People can live on the forest's fringes, but only at its sufferance. In a sense the fighting in this theater was a struggle between man and the primeval forest. The forest won; man withdrew, defeated by the masses of green and the diseases lurking there. That awesome power still lies in wait, ready to shatter anyone who defies it. If you want to live in the jungle you must treat it with great respect and keep your distance. Maugham saw that, Gauguin saw it, and so did Robert Louis Stevenson. Even I, cosseted now by all the achievements of modern technology, know that this trip, like my last one here, will alter me in ways I cannot now know. Yet you cannot resent nature. It is too enormous. Besides, it didn't

ask

you to come. You are here because the Japanese brought you the first time and left wounds which cannot heal without this second trip. You can, of course, resent the Japanese. I did. I still do.

Our trip back to the Canal is hurried. Landings after dark are forbidden in the islands; there are no runway lights, no navigational aids to guide fliers, only the bush and the glaucous, phosphorescent sea waiting to swallow you below. Bob puts us down neatly in a thickening twilight, and a friend drives me over the Matanikau to Honiara. The hotel pool is lighted, and several middle-aged Japanese men are leaping in and out of it, enlivening their horseplay with jubilant shouts. As I pick up my key the clerk genially suggests that I join them. A dip would be refreshing, but I shake my head. I need rest. Tomorrow I fly to an island whose very name evokes terror. It is Tarawa.