Goodbye, Darkness (9 page)

It came and they held. And held. And held. To the amazement of the world, which had seen resistance to Dai Nippon crumble everywhere else — the siege of Singapore had lasted just seven days when the British general surrendered eighty-five thousand Empire troops to thirty thousand Japanese — MacArthur's men, ridden by malaria, beriberi, smallpox, dysentery, hookworm, dengue fever, and pellagra, repulsed Homma's January offensive and, when he attempted two amphibious landings behind their lines, flung the invaders into the sea. Again and again the American regulars and their Filipino allies barred the enemy from penetrating deeper than the midriff of the peninsula. They thought they could retake Manila, which, at the time, seemed a distinct possibility. Homma was a bumbling commander, and his troops, also afflicted by diseases, were second-rate; Japan's elite divisions were attacking the Malay Barrier, south of Singapore. All MacArthur's men needed was help from the United States. And therein lies a tragic tale.

They had every reason to believe that convoys were on the way. Roosevelt cabled Manuel Quezon, president of the Philippine Commonwealth, then on Corregidor: “I can assure you that every vessel available is bearing … the strength that will eventually crush the enemy. … I give to the people of the Philippines my solemn pledge that their freedom will be retained. … The entire resources in men and materials of the United States stand behind that pledge.” General George C. Marshall, FDR's army chief of staff, radioed MacArthur: “A stream of four-engine bombers, previously delayed by foul weather, is enroute. … Another stream of similar bombers started today from Hawaii staging at new island fields. Two groups of powerful medium bombers of long range and heavy bomb-load capacity leave this week. Pursuit planes are coming on every ship we can use. … Our strength is to be concentrated and it should exert a decisive effect on Japanese shipping and force a withdrawal northward.”

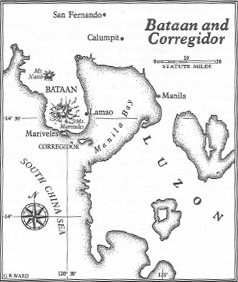

All this was untrue. Not a plane, not a warship, not a single U.S. reinforcement reached Bataan or Corregidor. The only possible explanation for arousing false expectations on the peninsula was that Washington was trying to buy time for other, more defensible outposts. As the truth sank in, the men facing Homma became embittered. Unaware that MacArthur had to remain on the island of Corregidor — “the Rock” — because its communications center provided his only contact with Washington, they scornfully called the general “Dugout Doug.” That was cruel, and unjust. But if ever men were entitled to a scapegoat, they were. Quite apart from the Japanese, they faced Bataan's almost unbelievable jungle. Cliffs are unscalable. Rivers are treacherous. Behind huge

nara

(mahogany) trees, eucalyptus trees, ipils, and tortured banyans, almost impenetrable screens are formed by tropical vines, creepers, and bamboo. Beneath these lie sharp coral outcroppings, fibrous undergrowth, and alang grass inhabited by pythons. In the early months of the year, when the battle was fought, rain poured down almost steadily. The water was contaminated. MacArthur's men ate roots, leaves, papayas, monkey meat, wild chickens, and wild pigs. They sang, to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”:

Dugout Doug MacArthur lies ashakin' on the Rock

Safe from all the bombers and from any sudden shock

…

And one soldier wrote:

We're the battling bastards of Bataan:

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam,

No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces,

No rifles, no planes, or artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn

.

Yet they fought on, with a devotion which would puzzle the generation of the 1980s. More surprising, in many instances it would have baffled the men they themselves were before Pearl Harbor. Among MacArthur's ardent infantrymen were cooks, mechanics, pilots whose planes had been shot down, seamen whose ships had been sunk, and some civilian volunteers. One civilian was a saddle-shoed American youth, a typical Joe College of that era who had been in the Philippines researching an anthropology paper. A few months earlier he had been an isolationist whose only musical interest was Swing. He had used an accordion to render tunes like “Deep Purple” and “Moonlight Cocktail.” Captured and sentenced to be shot, he made a last request. He wanted to die holding his accordion. This was granted, and he went to the wall playing “God Bless America.” It was that kind of time.

Only in early spring, when Homma was strengthened by twenty-two thousand fresh troops, howitzers, and fleets of Mitsubishis and Zeroes, did the Filipinos and Americans on Bataan Peninsula surrender. Then Corregidor, the bone in the throat of Manila Bay, held out for another exhausting month. Even so, Marines and bluejackets entrenched on the island's beaches killed half the Nipponese attack force. And it wasn't until June 6 that formal resistance ended, when a Jap hauled down the last American flag and ground it under his heel as a band played “Kimigayo,” his national anthem.

Nevertheless, the capitulation was the largest in U.S. history. For those who had survived to surrender on Bataan, the worst lay ahead: the ten-day, seventy-five-mile, notorious Death March to POW cages in northern Luzon. Jap guards began shooting prisoners who collapsed in the sun and suffocating dust beneath the pitiless sky. Next they withheld water from men dying of thirst. Beatings followed, and beheadings and torture. No one knows how many Allied soldiers perished during this Gethsemane, but most estimates run between seven and ten thousand. After the war the Filipinos decided to pay tribute to these martyrs with signposts marking each kilometer on Route 3, which was paved and rechristened MacArthur Highway. Each sign bore a silhouette of three stumbling Allied infantrymen trying to help one another, and travelers were told how far the Death Marchers had struggled at that point. It is sad to note that over half the signs have vanished, lost through neglect or taken by sightseers. This is

that

kind of time.

But other memorials are intact, though not always where one might expect to find them. The airstrip where MacArthur lost most of his B-17 air force is merely another B-52 runway. The vital Calumpit Bridge is identifiable only by an odd reference point: a soft-drink bottling factory surrounded by weeds. There are no plaques or shafts in the rainforests where the beleaguered Filipinos and Americans counterattacked Homma's troops, driving them back and back. However, in the village, or

barrio

, of Lamao, which lies on the bay side of the peninsula, a stone identifies the spot where Major General Edward P. King, Jr., the Bataan commander, capitulated on April 9, 1942, and in Mariveles, on the southern tip, an American rifle is cemented into a block, with a GI helmet welded to the butt of the gun. If you charter a helicopter, monuments may be found on the slopes of the peninsula's towering heights, Mount Mariveles and Mount Natib. One inscription reads, “Our mission is to remember”; another, in Tagalog, the native tongue, marks the “Damabana Nang Kagitingan” — the “Altar of Valor.” A relief map with colored red and blue lights shows successive Japanese and Allied positions on the peninsula. It is interesting to note that the altar is the work of Ferdinand E. Marcos, who, as a junior officer here (he was a

third

lieutenant), was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses, two Silver Stars, and two Purple Hearts, making him the war's most decorated Filipino. If Mussolini made trains run on time, it can at least be said that Marcos lets the dead lie in style. There is just one happily discordant note. Chiseled letters bear the democratic message “To Live in Freedom's Light Is the Right of Mankind.” Above it stands a crucifix formed of two parallel uprights and two horizontal bars. It can only be described as a double cross.

The easiest way to see Bataan, if you can afford it, is by helicopter; next easiest is by rented launch, which can take you from Manila to Mariveles — where tadpole-shaped Corregidor is visible, three miles from the peninsula — in less than two hours. But if you really want to steep yourself in Bataan's synoptic past, you must go by land. Since there is no rail service and buses are unreliable, this means in a car, preferably with four-wheel drive, because ruts and potholes pit MacArthur Highway. Lack of maintenance characterizes the Pacific's adoption of occidental modes almost everywhere. It may even be found in the tiny central Pacific Republic of Nauru, whose precious phosphate deposits are said to give its six thousand people a per capita income of over forty thousand dollars a year. If a car breaks down on Nauru, it is ditched and replaced with another.

There are no limousines on Bataan, and very few cars. The typical vehicle is a wagon drawn by a horse or a bullock. To park and enter a

barrio

is to move back to the Stone Age. Until MacArthur retreated into the peninsula, the inhabitants lived as their ancestors had, content in their insularity. After the war most of them returned to it. There are a few signs of the twentieth century there — an Exxon refinery at Lamao and a few tiny huts with rusting tin roofs where Hollywood films are shown. Even so, none of the natives seems to grasp what a refinery is, and the favorite recreation is watching cockfights. The government in Manila has outlawed them, but the peasants here don't know it; inland, they haven't even heard of Manila. Or, for that matter, of Bataan. It is their universe; they need no name for it. Except for the inhabitants of New Guinea and the northern Solomons, I know of no people more isolated from the outside world than the Bataanese. Here, on mountainous slopes within sight of the Philippines' capital, warriors hunt game with bows and arrows. Lithe Filipinas, striding past rice paddies with hand-carved wooden pitchforks balanced on their lovely heads, pass backdrops which might be taken from a Tarzan movie — waterfalls cascading in misty rainbows, orchids growing from canyon walls, and, from time to time, typhoons lashing the palm-fringed beaches.

Driving from the site of the Calumpit Bridge to Mariveles, you leave your car from time to time for excursions beyond the bayside

barrios

. The villages are all pretty much alike. There is no electricity — generators must be brought in for the rare movies — and virtually no line of communications to the world outside. Fishermen live in little straw shacks atop stilts. Their boats are outriggers. Inland, bullocks tug hand-hewn implements through rice paddies; the green sprouts are reaped by stooping women wading in the ankle-deep water. Their husbands climb palm trees to toss down coconuts, whose dried meat, copra, is their one export — the largest export, indeed, of the entire Philippines. An acrid scent bites the air; following it, you come upon a sugarcane field being burned off. Somehow the jungle seems friendlier to those who inhabit it. Men sing as they hammer away with rough mauls; women gossip while sitting in a circle, peeling leaves from cabbage plants; children hoot cheerfully as they play tag between lumbering water buffalo in shallow, muddy streams crowded on their banks with huge green shrubs whose wide leaves dip gracefully in all directions.

Twice, in the memory of their patriarchs, outsiders have arrived uninvited to use this as a killing ground: in the 1942 struggle and again when the victorious Americans returned three years later. No one knows how many peasants were slain by random shots and artillery bursts, but certainly more of them died than American civilians at home, who had a stake in the war yet were out of danger. And what, the Sergeant in me asks, did we give them in return? Well, there was venereal disease, hitherto unknown here. And insensate hatred between aliens, and efficient ways to destroy those you hated. Most cruelly, they were left with an uneasy feeling that these monstrous strangers had, for all their brutality, found clever ways of making life more tolerable and interesting. It was cruel because that way of life can never coexist with theirs. One recalls a prescient passage in the journal of Captain James Cook, the first European to discover the South Seas, in 1769: “I cannot avoid expressing it as my real opinion that it would have been far better for these poor people never to have known our superiority in the accommodations and arts that make life comfortable, than after once knowing it, to be again left and abandoned in their original incapacity of improvement. Indeed they cannot be restored to that happy mediocrity in which they lived before we discovered them if the intercourse between us should be discontinued.”

I am aboard a helicopter, descending through a blue mist between Corregidor's sheer cliffs toward the old Fort Drum parade ground. From this height the island seems larger than expected — about the size of Manhattan — and attractive. Of course, that was not always true. “Why, George,” Jean MacArthur said to George Kenney, her husband's air commander, when she returned to Manila Bay at the end of the war, “what have you done to Corregidor? I could hardly recognize it, when we passed it. It looks as though you had lowered it at least forty feet.” Certainly it had been lowered some. Between Japanese artillery in the first months of the war and Kenney's B-24s dumping four thousand tons of bombs on it later, the Rock had been changed beyond belief, denuded, among other things, of all vegetation. Today neither Jean nor Kenney would recognize the Rock. Two years after the war American troops reforested it, populated it with monkeys and small deer, and presented it to the Philippines as a national park. Only park police and caretakers live there now, though there is a small guesthouse on a bluff overlooking the North Dock for tourists who want to remain overnight. Like the picnics at Verdun in the 1920s, turning the Rock into a recreational spot may be an attempt to exorcise the desperate past.