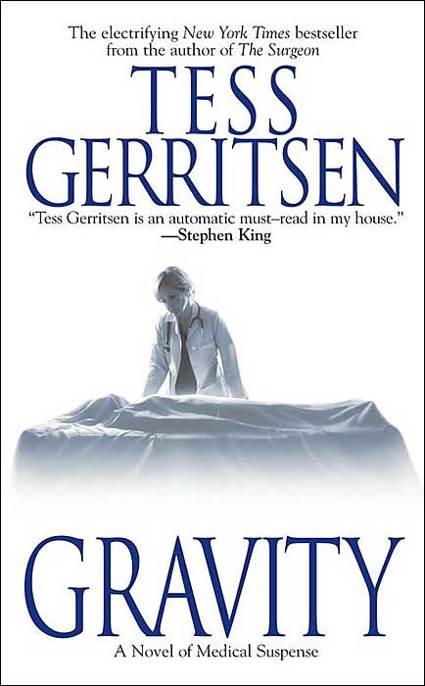

Gravity

Tess Gerritsen

Tess Gerritsen used to be a doctor, so it comes as no great surprise that the medical aspects of her latest thriller are absolutely convincing—even if most of the action happens in where few doctors have ever practiced—outer space.

Dr. Emma Watson and five other hand-picked astronauts are about to take part in the trip of a lifetime—studying living creatures in space. But an alien life form, found in the deepest crevices of the ocean floor, is accidentally brought aboard the shuttle Atlantis. This mutated alien life form makes the creatures in Aliens look like backyard pets.

Soon the crew are suffering severe stomach pains, violent convulsions, and eyes so bloodshot that a gallon of Murine wouldn’t help, brilliantly describes the difficulties of treating sick people a space module, and how the lack of gravity affects the process of taking blood and inserting a nasal tube. Dr. Watson does her best, but her colleagues die off one by one and the people at NASA don’t want to risk bringing the platform back to earth. Only Emma’s husband, doctor/astronaut himself, refuses to give up on her. As we read along, eyes popping out of our heads, all that’s missing is one of bland NASA voices saying, “Houston, we have a problem—we’re being attacked by tiny little creatures that are part human, part frog, and part mouse.”

30 Degrees South, 90.30 Degrees West

He was gliding on the edge of the abyss.

Below him yawned the watery blackness of a frigid underworld, where the sun had never penetrated, where the only light was the fleeting spark of a bioluminescent creature. Lying prone in the formfitting body pan of Deep Flight IV, his head cradled in the acrylic nose cone, Dr. Stephen D. Ahearn had the exhilarating sensation of soaring, untethered, through the vastness of space.

In the beams of his wing lights he saw the gentle and continuous drizzle of organic debris falling from the light-drenched waters far above. They were the corpses of protozoans, drifting down through thousands of feet of water to their final graveyard on the ocean floor.

Gliding through that soft rain of debris, he guided Deep Flight along the underwater canyon’s rim, keeping the abyss to his port side, the plateau floor beneath him. Though the sediment was seemingly barren, the evidence of life was everywhere. Etched in the ocean floor were the tracks and plow marks of wandering creatures, now safely concealed in their cloak of sediment. He saw evidence of man as well, a rusted length of chain, sinuously around a fallen anchor, a soda pop bottle, half-submerged in ooze.

Ghostly remnants from the alien world above.

A startling sight suddenly loomed into view. It was like coming across an underwater grove of charred tree trunks. The objects were black-smoker chimneys, twenty-foot tubes formed by dissolved minerals swirling out of cracks in the earth’s crust. With joysticks, he maneuvered Deep Flight gently starboard, to avoid chimneys.

“I’ve reached the hydrothermal vent,” he said. “Moving at two knots, smoker chimneys to port side.”

“How’s she handling?” Helen’s voice crackled through his earpiece.

“Beautifully. I want one of these babies for my own.” She laughed. “Be prepared to write a very big check, Steve. You spot the nodule field yet? It should be dead ahead.” Ahearn was silent for a moment as he peered through the watery murk. A moment later he said, “I see them.” The manganese nodules looked like lumps of coal scattered across the ocean floor. Strangely, almost bizarrely, smooth, by minerals solidifying around stones or grains of sand, they were a highly prized source of titanium and other precious metals. But he ignored the nodules. He was in search of a prize far more valuable.

“I’m heading down into the canyon,” he said.

With the joysticks he steered Deep Flight over the plateau’s edge. As his velocity increased to two and a half knots, the wings, designed to produce the opposite effect of an airplane wing, dragged the sub downward. He began his descent into the abyss.

“Eleven hundred meters,” he counted off. “Eleven fifty…”

“Watch your clearance. It’s a narrow rift. You monitoring water temperature?”

“It’s starting to rise. Up to fifty-five degrees now.”

“Still a ways from the vent. You’ll be in hot water in another two thousand meters.” A shadow suddenly swooped right past Ahearn’s face. He flinched, inadvertently jerking the joystick, sending the craft to starboard. The hard jolt of the sub against the canyon wall a clanging shock wave through the hull.

“Jesus!”

“Status?” said Helen. “Steve, what’s your status?” He was hyperventilating, his heart slamming in panic against the body pan. The hull. Have I damaged the hull? Through the harsh sound of his own breathing, he listened for the groan of giving way, for the fatal blast of water. He was thirty-six feet beneath the surface, and over one hundred atmospheres of pressure were squeezing in on all sides like a fist. A breach in hull, a burst of water, and he would be crushed.

“Steve, talk to me!”

Cold sweat soaked his body. He finally managed to speak. “I got startled—collided with the canyon wall—”

“Is there any damage?”

He looked out the dome. “I can’t tell. I think I bumped against the cliff with the forward sonar unit.”

“Can you still maneuver?”

He tried the joysticks, nudging the craft to port. “Yes. Yes.” released a deep breath. “I think I’m okay. Something swam right past my dome. Got me rattled.”

“Something?”

“It went by so fast! Just this streak—like a snake whipping by.”

“Did it look like a fish’s head on an eel’s body?”

“Yes. Yes, that’s what I saw.”

“Then it was an eelpout. Thermarces cerberus.”

Cerberus, thought Ahearn with a shudder. The three-headed dog guarding the gates of hell.

“It’s attracted to the heat and sulfur,” said Helen. “You’ll see more of them as you get closer to the vent.”

If you say so. Ahearn knew next to nothing about marine biology.

The creatures now drifting past his acrylic head dome were merely objects of curiosity to him, living signposts pointing the to his goal.

With both hands steady at the controls now, he maneuvered Deep Flight IV deeper into the abyss.

Two thousand meters. Three thousand.

What if he had damaged the hull?

Four thousand meters, the crushing pressure of water increasing linearly as he descended. The water was blacker now, colored by plumes of sulfur from the vent below. The wing lights scarcely penetrated that thick mineral suspension. Blinded by the swirls of sediment, he maneuvered out of the sulfur-tinged water, and his improved. He was descending to one side of the hydrothermal vent, out of the plume of magma-heated water, yet the external temperature continued to climb.

One hundred twenty degrees Fahrenheit.

Another streak of movement slashed across his field of vision.

This time he managed to maintain his grip on the controls. He saw more eelpouts, like fat snakes hanging head down as though suspended in space. The water spewing from the vent below was rich in heated hydrogen sulfide, a chemical that was toxic and incompatible with life. But even in these black and poisonous waters, had managed to bloom, in shapes fantastic and beautiful. Attached to the canyon wall were swaying Riftia worms, six feet long, with feathery scarlet headdresses. He saw clusters of giant clams, white-shelled, with tongues of velvety red peeking out.

And he crabs, eerily pale and ghostlike as they scuttled among the crevices.

Even with the air-conditioning unit running, he was starting to feel the heat.

Six thousand meters. Water temperature one hundred eighty degrees. In the plume itself, heated by boiling magma, the temperatures would be over five hundred degrees. That life could even here, in utter darkness, in these poisonous and superheated waters, seemed miraculous.

“I’m at six thousand sixty,” he said. “I don’t see it.” In his earphone, Helen’s voice was faint and crackling. “There’s a shelf jutting out from the wall. You should see it at around six thousand eighty meters.”

“I’m looking.”

“Slow your descent. It’ll come up quickly.”

“Six thousand seventy, still looking. It’s like pea soup down here. Maybe I’m at the wrong position.”

“…sonar readings… collapsing above you!” Her message was lost in static.

“I didn’t copy that. Repeat.”

“The canyon wall is giving way! There’s debris falling toward you. Get out of there!” The loud pings of rocks hitting the hull made him jam the joysticks forward in panic. A massive shadow plummeted down through the murk just ahead and bounced off a canyon shelf, sending a fresh rain of debris into the abyss. The pings accelerated.

Then there was a deafening clang, and the accompanying jolt was like a fist slamming into him.

His head jerked, his jaw slamming into the body pan. He felt himself tilting sideways, heard the sickening groan of metal as starboard wing scraped over jutting rocks. The sub kept rolling, sediment swirling past the dome in a disorienting cloud.

He hit the emergency-weight-drop lever and fumbled with the joysticks, directing the sub to ascend. Deep Flight IV lurched forward, metal screeching against rock, and came to an unexpected halt. He was frozen in place, the sub tilted starboard.

He worked at the joysticks, thrusters at full ahead.

No response.

He paused, his heart pounding as he struggled to maintain control over his rising panic. Why wasn’t he moving? Why was the sub not responding?

He forced himself to scan the two digital display units. Battery power intact. AC unit still functioning. Depth reading, six thousand eighty-two meters.

The sediment slowly cleared, and shapes took form in the beam of his port wing light. Peering straight ahead through the dome, saw an alien landscape of jagged black stones and bloodred Riftia worms. He craned his neck sideways to look at his starboard wing.

What he saw sent his stomach into a sickening tumble.

The wing was tightly wedged between two rocks. He could not move forward. Nor could he move backward. I am trapped in a tomb, nineteen thousand feet under the sea.

“…copy? Steve, do you copy?”

He heard his own voice, weak with fear, “Can’t move—starboard wing wedged—”

“…port-side wing flaps. A little yaw might wiggle you loose.”

“I’ve tried it. I’ve tried everything. I’m not moving.” There was dead silence over the earphones. Had he lost them?

Had he been cut off? He thought of the ship far above, the deck gently rolling on the swells. He thought of sunshine. It had been beautiful sunny day on the surface, birds gliding overhead. The sky a bottomless blue. Now a man’s voice came on. It was that of Palmer Gabriel, the man who had financed the expedition, speaking calmly and in control, as always. “We’re starting rescue procedures, Steve. A sub is already being lowered. We’ll get you up to the surface as soon as we can.” There was a pause, then, “Can you see anything? What are your surroundings?”

“I—I’m resting on a shelf just above the vent.”

“How much detail can you make out?”

“What?”

“You’re at six thousand eighty-two meters. Right at the depth we were interested in. What about that shelf you’re on? The rocks?”

I am going to die, and he is asking about the fucking rocks.

“Steve, use the strobe. Tell us what you see.” He forced his gaze to the instrument panel and flicked the strobe switch.

Bright bursts of light flashed in the murk. He stared at the newly revealed landscape flickering before his retinas. Earlier he had focused on the worms. Now his attention shifted to the immense field of debris scattered across the shelf floor. The rocks were coal black, like magnesium nodules, but these had jagged edges, like congealed shards of glass.

Peering to his right, at freshly fractured rocks trapping his wing, he suddenly realized what he was looking at.

“Helen’s right,” he whispered.

“I didn’t copy that.”

“She was right! The iridium source—I have it in clear view—”

“You’re fading out. Recommend you…” Gabriel’s voice broke up into static and went dead.

“I did not copy. Repeat, I did not copy!” said Ahearn.

There was no answer.

He heard the pounding of his heart, the roar of his own breathing.

Slow down, slow down. Using up my oxygen too fast… Beyond the acrylic dome, life drifted past in a delicate dance through poisonous water. As the minutes stretched to hours, he watched the Riftia worms sway, scarlet plumes combing for nutrients. He saw an eyeless crab slowly scuttle across the field stones.

The lights dimmed. The air-conditioning fans abruptly fell silent.

The battery was dying.

He turned off the strobe light. Only the faint beam of the port wing light was shining now. In a few minutes he would begin to feel the heat of that one-hundred-eighty-degree magma-charged water.

It would radiate through the hull, would slowly cook him alive in his own sweat. Already he felt a drop trickle from his scalp and slide down his cheek. He kept his gaze focused on that single crab, delicately prancing its way across the stony shelf.

The wing light flickered.

And went out.