Gravity's Rainbow (42 page)

Authors: Thomas Pynchon

• • • • • • •

The great cusp—green equinox and turning, dreaming fishes to young ram, watersleep

to firewaking, bears down on us. Across the Western Front, up in the Harz in Bleicheröde,

Wernher von Braun, lately wrecked arm in a plaster cast, prepares to celebrate his

33rd birthday. Artillery thunders through the afternoon. Russian tanks raise dust

phantoms far away over the German leas. The storks are home, and the first violets

have appeared.

At “The White Visitation,” days along the chalk piece of seacoast now are fine and

clear. The office girls are bundling into fewer sweaters, and breasts peaking through

into visibility again. March has come in like a lamb. Lloyd George is dying. Stray

visitors are observed now along the still-forbidden beach, sitting among obsolescent

networks of steel rod and cable, trousers rolled to the knee or hair unsnooded, chilly

gray toes stirring the shingle. Just offshore, underwater, run miles of secret piping,

oil ready at a valve-twist to be released and roast German invaders who belong back

in dreams already old . . . fuel waiting hypergolic ignition that will not come unless

now as some junior-bureaucratic rag or May uprising of the spirit, to Bavarian tunesmith

Carl Orff’s lively

O, O, O,

To-tus flore-o!

Iam amore virginali

Totus ardeo . . .

all this fortress coast alight, Portsmouth to Dungeness, blazing for the love of spring.

Plots to this effect hatch daily among the livelier heads at “The White Visitation”—the

winter of dogs, of black snowfalls of issueless words, is ending. Soon it will be

behind us. But once there, behind us—will it still go on emanating its hooded cold,

however the fires burn at sea?

At the Casino Hermann Goering, a new regime has been taking over. General Wivern’s

is now the only familiar face, though he seems to’ve been downgraded. Slothrop’s own

image of the plot against him has grown. Earlier the conspiracy was monolithic, all-potent,

nothing he could ever touch. Until that drinking game, and that scene with that Katje,

and both the sudden good-bys. But now—

Proverbs for Paranoids, 1: You may never get to touch the Master, but you can tickle

his creatures.

And then, well, he is lately beginning to find his way into one particular state of

consciousness, not a dream certainly, perhaps what used to be called a “reverie,”

though one where the colors are more primaries than pastels . . . and at such times

it seems he has touched, and stayed touching, for a while, a soul we know, a voice

that has more than once spoken through research-facility medium Carroll Eventyr: the

late Roland Feldspath again, long–co-opted expert on control systems, guidance equations,

feedback situations for this Aeronautical Establishment and that. Seems that, for

personal reasons, Roland has remained hovering over this Slothropian space, through

sunlight whose energy he barely feels and through storms that tickled his back with

static electricity has Roland been whispering from eight kilometers, the savage height,

stationed as he has been along one of the Last Parabolas—flight paths that must never

be taken—working as one of the invisible Interdictors of the stratosphere now, bureaucratized

hopelessly on that side as ever on this, he keeps his astral meathooks in as well

as can be expected, curled in the “sky” so tense with all the frustrations of trying

to reach across, with the impotence of certain dreamers who try to wake or talk and

cannot, who struggle against weights and probes of cranial pain that it seems could

not be borne waking, he waits, not necessarily for the aimless entrances of boobs

like Slothrop here—

Roland shivers. Is

this

the one? This? to be figurehead for the latest passage? Oh, dear. God have mercy:

what storms, what monsters of the Aether could this Slothrop ever charm away for anyone?

Well, Roland must make the best of it, that’s all. If they get this far, he has to

show them what he knows about Control. That’s one of his death’s secret missions.

His cryptic utterances that night at Snoxall’s about economic systems are merely the

folksy everyday background chatter over here, a given condition of being. Ask the

Germans especially. Oh, it is a real sad story, how shoddily their Schwärmerei for

Control was used by the folks in power. Paranoid Systems of History (PSH), a short-lived

periodical of the 1920s whose plates have all mysteriously vanished, natch, has even

suggested, in more than one editorial, that the whole German Inflation was created

deliberately, simply to drive young enthusiasts of the Cybernetic Tradition into Control

work: after all, an economy inflating, upward bound as a balloon, its own definition

of Earth’s surface drifting upward in value, uncontrolled, drifting with the days,

the feedback system expected to maintain the value of the mark constant having, humiliatingly,

failed. . . . Unity gain around the loop, unity gain, zero change, and hush, that

way, forever, these were the secret rhymes of the childhood of the Discipline of Control—secret

and terrible, as the scarlet histories say. Diverging oscillations of any kind were

nearly the Worst Threat. You could not pump the swings of these playgrounds higher

than a certain angle from the vertical. Fights broke up quickly, with a smoothness

that had not been long in coming. Rainy days never had much lightning or thunder to

them, only a haughty glass grayness collecting in the lower parts, a monochrome overlook

of valleys crammed with mossy deadfalls jabbing roots at heaven not entirely in malign

playfulness (as some white surprise for the elitists up there paying no mind, no . . .),

valleys thick with autumn, and in the rain a withering, spinsterish brown behind the

gold of it . . . very selectively blighted rainfall teasing you across the lots and

into the back streets, which grow ever more mysterious and badly paved and more deeply

platted, lot giving way to crooked lot seven times and often more, around angles of

hedge, across freaks of the optical daytime until we have passed, fevered, silent,

out of the region of streets itself and into the countryside, into the quilted dark

fields and the wood, the beginning of the true forest, where a bit of the ordeal ahead

starts to show, and our hearts to feel afraid . . . but just as no swing could ever

be thrust above a certain height, so, beyond a certain radius, the forest could be

penetrated no further. A limit was always there to be brought to. It was so easy to

grow up under that dispensation. All was just as wholesome as could be. Edges were

hardly ever glimpsed, much less flirted at or with. Destruction, oh, and demons—yes,

including Maxwell’s—were there, deep in the woods, with other beasts vaulting among

the earthworks of your safety. . . .

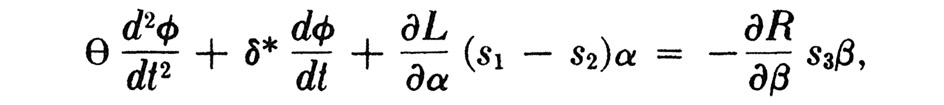

So was the Rocket’s terrible passage reduced, literally, to bourgeois terms, terms

of an equation such as that elegant blend of philosophy and hardware, abstract change

and hinged pivots of real metals which describes motion under the aspect of yaw control:

preserving, possessing, steering between Scylla and Charybdis the whole way to Brennschluss.

If any of the young engineers saw correspondence between the deep conservatism of

Feedback and the kinds of lives they were coming to lead

in the very process

of embracing it, it got lost, or disguised—none of them made the connection, at least

not while alive: it took death to show it to Roland Feldspath, death with its very

good chances for being Too Late, and a host of other souls feeling themselves, even

now, Rocketlike, driving out toward the stone-blue lights of the Vacuum under a Control

they cannot quite name . . . the illumination out here is surprisingly mild, mild

as heavenly robes, a feeling of population and invisible force, fragments of “voices,”

glimpses into

another order of being. . . .

Afterward, Slothrop would be left not so much with any clear symbol or scheme to it

as with some alkaline aftertaste of lament, an irreducible

strangeness

, a self-sufficiency nothing could get inside. . . .

Yes, sort of

German

, these episodes here. Well, these days Slothrop is even dreaming in the language.

Folks have been teaching him dialects, Plattdeutsch for the zone the British plan

to occupy, Thuringian if the Russians happen not to drive as far as Nordhausen, where

the central rocket works is located. Along with the language teachers come experts

in ordnance, electronics, and aerodynamics, and a fellow from Shell International

Petroleum named Hilary Bounce, who is going to teach him about propulsion.

It seems that early in 1941, the British Ministry of Supply let a £10,000 research

contract to Shell—wanted Shell to develop a rocket engine that would run on something

besides cordite, which was being used in those days to blow up various sorts of people

at the rate of oodles ’n’ oodles of tons an hour, and couldn’t be spared for rockets.

A team ramrodded by one Isaac Lubbock set up a static-test facility at Langhurst near

Horsham, and began to experiment with liquid oxygen and aviation fuel, running their

first successful test in August of ’42. Engineer Lubbock was a double first at Cambridge

and the Father of British Liquid Oxygen Research, and what he didn’t know about the

sour stuff wasn’t worth knowing. His chief assistant these days is Mr. Geoffrey Gollin,

and it is to Gollin that Hilary Bounce reports.

“Well, I’m an Esso man myself,” Slothrop thinks he ought to mention. “My old short

was a gasgobbler all right, but a gourmet. Any time it used that Shell I had to drop

a whole bottle of that Bromo in the tank just to settle that poor fucking Terraplane’s

plumbing down.”

“Actually,” the eyebrows of Captain Bounce, a 110% company man, going up and down

earnestly to help him out, “we handled only the transport and storage end of things

then. In those days, before the Japs and the Nazis you know, production and refining

were up to the Dutch office, in The Hague.”

Slothrop, poor sap, is remembering Katje, lost Katje, saying the name of her city,

whispering Dutch love-words as they moved down sea-mornings now another age, another

dispensation. . . .

Wait a minute.

“That’s Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij, N.V.?”

“Right.”

It’s also the negative of a recco photograph of the city, darkbrown, festooned with

water-spots, never enough time to let these dry out completely—

“Are you blokes

aware

,” they’re trying to teach him English English too, heaven knows why, and it keeps

coming out like Cary Grant, “that Jerry—old Jerry, you know—has been

in

that The Hague there, shooting his bloody rockets at that London, a-and

using

, the . . . Royal Dutch Shell headquarters

building

, at the Josef Israelplein if I remember correctly, for a radio

guidance

transmitter? What bizarre shit is

that

, old man?”

Bounce stares at him, jingling his gastric jewelry, not knowing what to make of Slothrop,

exactly.

“I mean,” Slothrop now working himself into a fuss over something that only disturbs

him, dimly, nothing to kick up a row over, is it? “doesn’t it strike you as just a

bit odd, you Shell chaps working on

your

liquid engine

your

side of the Channel you know, and

their

chaps firing

their

bloody things at you with your own . . . blasted . . . Shell transmitter tower, you

see.”

“No, I can’t see that it makes—what are you getting at? Surely they’d simply have

picked the tallest building they could find that’s in a direct line from their firing

sites to London.”

“Yes, and at the right

distance

too, don’t forget that—exactly twelve kilometers

from

the firing site. Hey? That’s exactly what I mean.” Wait, oh wait. Is

that

what he means?

“Well, I’d never thought of it that way.”

Neither have I, Jackson. Oh, me neither folks. . . .

Hilary Bounce and his Puzzled Smile. Another innocent, a low-key enthusiast like Sir

Stephen Dodson-Truck. But:

Proverbs for Paranoids, 2: The innocence of the creatures is in inverse proportion

to the immorality of the Master.

“I hope I haven’t said anything wrong.”

“Whyzat?”

“You look—” Bounce aspirating what he means to be a warm little laugh, “worried.”

Worried, all right. By the jaws and teeth of some Creature, some Presence so large

that nobody else can see it—there! that’s that monster I was telling you about.—That’s

no monster, stupid, that’s

clouds!

—No, can’t you

see?

It’s his

feet

— Well, Slothrop can feel this beast in the sky: its visible claws and scales are

being mistaken for clouds and other plausibilities . . . or else everyone has agreed

to

call them other names

when Slothrop is listening. . . .

“It’s only a ‘wild coincidence,’ Slothrop.”

He will learn to hear quote marks in the speech of others. It is a bookish kind of

reflex, maybe he’s genetically predisposed—all those earlier Slothrops packing Bibles

around the blue hilltops as part of their gear, memorizing chapter and verse the structures

of Arks, Temples, Visionary Thrones—all the materials and dimensions. Data behind

which always, nearer or farther, was the numinous certainty of God.