Gravity's Rainbow (5 page)

Authors: Thomas Pynchon

He has become obsessed with the idea of a rocket with his name written on it—if they’re

really set on getting him (“They” embracing possibilities far far beyond Nazi Germany)

that’s the surest way, doesn’t cost them a thing to paint his name

on every one, right?

“Yes, well, that can be useful,” Tantivy watching him funny, “can’t it, especially

in combat to, you know,

pretend

something like that. Jolly useful. Call it ‘operational paranoia’ or something. But—”

“Who’s pretending?” lighting a cigarette, shaking his forelock through the smoke,

“jeepers, Tantivy, listen, I don’t want to upset you but . . . I mean I’m four years

overdue’s what it is, it could happen

any time

, the next second, right, just suddenly . . . shit . . . just zero, just nothing . . .

and . . .”

It’s nothing he can see or lay hands on—sudden gases, a violence upon the air and

no trace afterward . . . a Word, spoken with no warning into your ear, and then silence

forever. Beyond its invisibility, beyond hammerfall and doomcrack, here is its real

horror, mocking, promising him death with German and precise confidence, laughing

down all of Tantivy’s quiet decencies . . . no, no bullet with fins, Ace . . . not

the Word, the one Word that rips apart the day. . . .

It was Friday evening, last September, just off work, heading for the Bond Street

Underground station, his mind on the weekend ahead and his two Wrens, that Norma and

that Marjorie, whom he must each keep from learning about the other, just as he was

reaching to pick his nose, suddenly in the sky, miles behind his back and up the river

mementomori

a sharp crack and a heavy explosion, rolling right behind, almost like a clap of

thunder. But not quite. Seconds later, this time from in front of him, it happened

again: loud and clear, all over the city. Bracketed. Not a buzzbomb, not that Luftwaffe.

“Not thunder either,” he puzzled, out loud.

“Some bloody gas main,” a lady with a lunchbox, puffy-eyed from the day, elbowing

him in the back as she passed.

“No it’s the

Ger

mans,” her friend with rolled blonde fringes under a checked kerchief doing some monster

routine here, raising her hands at Slothrop, “coming to get

him

, they especially

love

fat, plump Americans—” in a minute she’ll be reaching out to pinch his cheek and

wobble it back and forth.

“Hi, glamorpuss,” Slothrop said. Her name was Cynthia. He managed to get a telephone

number before she was waving ta-ta, borne again into the rush-hour crowds.

It was one of those great iron afternoons in London: the yellow sun being teased apart

by a thousand chimneys breathing, fawning upward without shame. This smoke is more

than the day’s breath, more than dark strength—it is an imperial presence that lives

and moves. People were crossing the streets and squares, going everywhere. Busses

were grinding off, hundreds of them, down the long concrete viaducts smeared with

years’ pitiless use and no pleasure, into hazegray, grease-black, red lead and pale

aluminum, between scrap heaps that towered high as blocks of flats, down side-shoving

curves into roads clogged with Army convoys, other tall busses and canvas lorries,

bicycles and cars, everyone here with different destinations and beginnings, all flowing,

hitching now and then, over it all the enormous gas ruin of the sun among the smokestacks,

the barrage balloons, power lines and chimneys brown as aging indoor wood, brown growing

deeper, approaching black through an instant—perhaps the true turn of the sunset—that

is wine to you, wine and comfort.

The Moment was 6:43:16 British Double Summer Time: the sky, beaten like Death’s drum,

still humming, and Slothrop’s cock—say what? yes lookit inside his GI undershorts

here’s a sneaky

hardon

stirring, ready to jump—well great God where’d

that

come from?

There is in his history, and likely, God help him, in his dossier, a peculiar sensitivity

to what is revealed in the sky. (But a

hardon?

)

On the old schist of a tombstone in the Congregational churchyard back home in Mingeborough,

Massachusetts, the hand of God emerges from a cloud, the edges of the figure here

and there eroded by 200 years of seasons’ fire and ice chisels at work, and the inscription

reading:

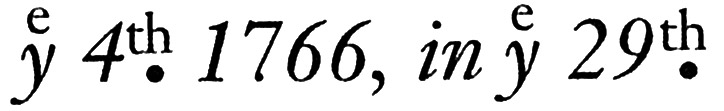

In Memory of Constant

Slothrop, who died March

year of his age.

Death is a debt to nature due,

Which I have paid, and so must you.

Constant saw, and not only with his heart, that stone hand pointing out of the secular

clouds, pointing directly at him, its edges traced in unbearable light, above the

whispering of his river and slopes of his long blue Berkshires, as would his son Variable

Slothrop, indeed all of the Slothrop blood one way or another, the nine or ten generations

tumbling back, branching inward: every one, except for William the very first, lying

under fallen leaves, mint and purple loosestrife, chilly elm and willow shadows over

the swamp-edge graveyard in a long gradient of rot, leaching, assimilation with the

earth, the stones showing round-faced angels with the long noses of dogs, toothy and

deep-socketed death’s heads, Masonic emblems, flowery urns, feathery willows upright

and broken, exhausted hourglasses, sunfaces about to rise or set with eyes peeking

Kilroy-style over their horizon, and memorial verse running from straight-on and foursquare,

as for Constant Slothrop, through bouncy Star Spangled Banner meter for Mrs. Elizabeth,

wife of Lt. Isaiah Slothrop (d. 1812):

Adieu my dear friends, I have come to this grave

Where Insatiate Death in his reaping hath brought me.

Till Christ rise again all His children to save,

I must lie, as His Word in the Scriptures hath taught me.

Mark, Reader, my cry! Bend thy thoughts on the Sky,

And in midst of prosperity, know thou may’st die.

While the great Loom of God works in darkness above,

And our trials here below are but threads of His Love.

To the current Slothrop’s grandfather Frederick (d. 1933), who in typical sarcasm

and guile bagged his epitaph from Emily Dickinson, without a credit line:

Because I could not stop for Death

He kindly stopped for me

Each one in turn paying his debt to nature due and leaving the excess to the next

link in the name’s chain. They began as fur traders, cordwainers, salters and smokers

of bacon, went on into glassmaking, became selectmen, builders of tanneries, quarriers

of marble. Country for miles around gone to necropolis, gray with marble dust, dust

that was the breaths, the ghosts, of all those fake-Athenian monuments going up elsewhere

across the Republic. Always elsewhere. The money seeping its way out through stock

portfolios more intricate than any genealogy: what stayed at home in Berkshire went

into timberland whose diminishing green reaches were converted acres at a clip into

paper—toilet paper, banknote stock, newsprint—a medium or ground for shit, money,

and the Word. They were not aristocrats, no Slothrop ever made it into the Social

Register or the Somerset Club—they carried on their enterprise in silence, assimilated

in life to the dynamic that surrounded them thoroughly as in death they would be to

churchyard earth. Shit, money, and the Word, the three American truths, powering the

American mobility, claimed the Slothrops, clasped them for good to the country’s fate.

But they did not prosper . . . about all they did was persist—though it all began

to go sour for them around the time Emily Dickinson, never far away, was writing

Ruin is formal, devil’s work,

Consecutive and slow—

Fail in an instant no man did,

Slipping is crash’s law,

still they would keep on. The tradition, for others, was clear, everyone knew—mine

it out, work it, take all you can till it’s gone then move on west, there’s plenty

more. But out of some reasoned inertia the Slothrops stayed east in Berkshire, perverse—close

to the flooded quarries and logged-off hillsides they’d left like signed confessions

across all that thatchy-brown, moldering witch-country. The profits slackening, the

family ever multiplying. Interest from various numbered trusts was still turned, by

family banks down in Boston every second or third generation, back into yet another

trust, in long rallentando, in infinite series just perceptibly, term by term, dying . . .

but never quite to the zero. . . .

The Depression, by the time it came, ratified what’d been under way. Slothrop grew

up in a hilltop desolation of businesses going under, hedges around the estates of

the vastly rich, half-mythical cottagers from New York lapsing back now to green wilderness

or straw death, all the crystal windows every single one smashed, Harrimans and Whitneys

gone, lawns growing to hay, and the autumns no longer a time for foxtrots in the distances,

limousines and lamps, but only the accustomed crickets again, apples again, early

frosts to send the hummingbirds away, east wind, October rain: only winter certainties.

In 1931, the year of the Great Aspinwall Hotel Fire, young Tyrone was visiting his

aunt and uncle in Lenox. It was in April, but for a second or two as he was coming

awake in the strange room and the racket of big and little cousins’ feet down the

stairs, he thought of winter, because so often he’d been wakened like this, at this

hour of sleep, by Pop, or Hogan, bundled outside still blinking through an overlay

of dream into the cold to watch the Northern Lights.

They scared the shit out of him. Were the radiant curtains just about to swing open?

What would the ghosts of the North, in their finery, have to show him?

But this was a spring night, and the sky was gusting red, warm-orange, the sirens

howling in the valleys from Pittsfield, Lenox, and Lee—neighbors stood out on their

porches to stare up at the shower of sparks falling down on the mountainside . . .

“Like a meteor shower,” they said, “Like cinders from the Fourth of July . . .” it

was 1931, and those were the comparisons. The embers fell on and on for five hours

while kids dozed and grownups got to drink coffee and tell fire stories from other

years.

But what Lights were these? What ghosts in command? And suppose, in the next moment,

all of it, the complete night,

were

to go out of control and curtains part to show us a winter no one has guessed at. . . .

6:43:16 BDST—

in the sky right now

here is the same unfolding, just about to break through, his face deepening with

its light, everything about to rush away and he to lose himself, just as his countryside

has ever proclaimed . . . slender church steeples poised up and down all these autumn

hillsides, white rockets about to fire, only seconds of countdown away, rose windows

taking in Sunday light, elevating and washing the faces above the pulpits defining

grace, swearing

this is how it does happen—yes the great bright hand reaching out of the cloud

. . . .

• • • • • • •

On the wall, in an ornate fixture of darkening bronze, a gas jet burns, laminar and

gently singing—adjusted to what scientists of the last century called a “sensitive

flame”: invisible at the base, as it issues from its orifice, fading upward into smooth

blue light that hovers several inches above, a glimmering small cone that can respond

to the most delicate changes in the room’s air pressure. It registers visitors as

they enter and leave, each curious and civil as if the round table held some game

of chance. The circle of sitters is not at all distracted or hindered. None of your

white hands or luminous trumpets here.

Camerons officers in parade trews, blue puttees, dress kilts drift in conversing with

enlisted Americans . . . there are clergymen, Home Guard or Fire Service just off

duty, folds of wool clothing heavy with smoke smell, everyone grudging an hour’s sleep

and looking it . . . ancient Edwardian ladies in crepe de Chine, West Indians softly

plaiting vowels round less flexible chains of Russian-Jewish consonants. . . . Most

skate tangent to the holy circle, some stay, some are off again to other rooms, all

without breaking in on the slender medium who sits nearest the sensitive flame with

his back to the wall, reddish-brown curls tightening close as a skullcap, high forehead

unwrinkled, dark lips moving now effortless, now in pain:

“Once transected into the realm of Dominus Blicero, Roland found that all the signs

had turned against him. . . . Lights he had studied so well as one of you, position

and movement, now gathered there at the opposite end, all in dance . . . irrelevant

dance. None of Blicero’s traditional progress, no something new . . . alien. . . .

Roland too became conscious of the wind, as his mortality had never allowed him. Discovered

it so . . . so joyful, that the arrow must veer into it. The wind had been blowing

all year long, year after year, but Roland had felt only the secular wind . . . he

means, only his personal wind. Yet . . . Selena, the wind, the wind’s everywhere. . . .”