Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (42 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

“Supposing we are lucky in the case of temple-entry, will they let us fetch water from the wells?” Ambedkar asked.

“Sure,” Gandhi replied. “This is bound to follow.”

Ambedkar hesitated. What he wanted from Gandhi, the Mahatma wasn’t ready to provide—an unambiguous denunciation of the caste system to show he was in earnest about his contention that all Hindus were created equal.

Ambedkar had agreed to join the board of the Harijan Sevak Sangh, whose constitution said as much, promising Harijans “absolute equality with the rest of Hindus” and requiring its members to declare: “I do not consider any human being as inferior to me in status and I shall strive my utmost to live by that belief.”

But within a year he resigned, convinced that this Gandhian organization dedicated to the service of his people was dominated by caste Hindus who were basically uninterested in mobilizing Harijans, as Ambedkar had proposed, in “a campaign all over India to secure to the Depressed Classes the enjoyment of their civic rights.”

Finally Ambedkar concluded that the temple-entry legislation had to be read as an insult, another reason to move away from the Mahatma. “

Sin and immorality cannot become tolerable because a majority is addicted to them or because the majority chooses to practice them,” he said. “If untouchability is a sinful and immoral custom, in the view of the Depressed Classes it must be destroyed without any hesitation even if it was acceptable to the majority.”

The same issue—whether Harijan basic rights could be put to a vote by caste Hindus—came up in the conflict over

Guruvayur temple. Still locked up at Yeravda but permitted by the authorities to agitate on Harijan issues from behind prison walls, Gandhi kept scheduling and postponing a fast on the opening of the celebrated Krishna temple. A poll was taken in the temple’s surroundings, confirming his belief that most caste Hindus were now ready to worship with Harijans. But the temple remained closed to them until after independence in 1947.

As late as 1958, ten years after Gandhi’s murder, a deflated and dispirited Harijan Sevak Sangh was counting it as a victory that a couple more temples in Benares were at last being opened to Harijans whose equality it had proclaimed a quarter of a century earlier.

In May 1933, when Gandhi finally started his next fast—his second over untouchability in seven months—he was immediately released from jail. Though it lasted twenty-one days—two weeks longer than the so-called epic fast—this second round caused less of a stir. Tagore wrote to say it was a mistake. Nehru, still in jail in Allahabad, threw up his hands. “What can I say about matters I do not understand?” he wrote in a letter to Gandhi.

Ambedkar by this time was looking the other way. Within two years, his movement ended the temple-entry campaigns it had been carrying on in a desultory fashion over the previous decade.

The time had come, he proclaimed, for untouchables—now starting to call themselves

Dalits, not Harijans—to give up on Hinduism. “I was born a Hindu and have suffered the consequences of untouchability,” he said and then immediately vowed: “I will not die a Hindu.”

If any admiration, any ambivalence lingered in Ambedkar’s feelings about Gandhi after their final falling-out, he labored to repress it. Much of his energy in his late years went into a renewal—and escalation—of bitter polemics against him. “As a Mahatma he may be trying to spiritualize politics,” Ambedkar would write. “Whether he has succeeded in it or not, politics have certainly commercialized him. A politician must know that society cannot bear the whole truth, that he must not speak the whole truth if speaking the whole truth is bad for his politics.” Gandhi refuses to launch a frontal attack on the caste system, this disillusioned, brainy antagonist finally argues, out of fear that “he will lose his place in politics.”

Which is why, he concludes, “The Mahatma appears not to believe in thinking.”

The inconsistency was as much Ambedkar’s as Gandhi’s. The Poona

Pact might have given them a basis for a fruitful division of labor, with Gandhi working to soften up Hindu attachment to the practice of untouchability, leaving room for Ambedkar to mobilize the impoverished and oppressed people Gandhi had named Harijans. More than politics and Ambedkar’s ambition got in the way. Gandhi wasn’t interested in mobilization outside the Congress. Ambedkar wanted his fair share of power but wasn’t prepared to be patronized, which was what would happen, he seemed sure, if he ever surrendered his independence to the Congress. Putting his case against Gandhi in the simplest terms, Ambedkar said: “

Obviously, he would like to uplift the Untouchables if he can but not by offending the Hindus.” That sentence contains the essence of their conflict. Ambedkar had ceased to think of untouchables as Hindus; Gandhi had not. The basic question was whether they’d be better off in the India of the future as a segregated minority and interest group battling for its rights or as a tolerated adjunct to the majority with recognized rights, an issue, it’s fair to say, that remains unresolved after nearly eight decades.

After all his hard bargaining, the untouchable leader eventually discovered that the concessions he’d made to secure an agreement with the fasting Mahatma hadn’t elevated him to a national position; he was to get there by another route. As the years wore on, he found himself leader of a series of small cash-starved opposition parties whose influence seldom extended beyond his Mahar base in what became the state of Maharashtra. For this, with mounting asperity, he blamed Gandhi and the Congress.

But there’s suggestive if somewhat sketchy evidence that, fifteen years after the pact, it may have been Gandhi who advanced Ambedkar’s name for a position in independent India’s first cabinet. As law minister, he then became the principal author of the 1950 constitution whose Article 17 formally abolished untouchability, a denouement Gandhi did not live to see. So the man now revered as Babasaheb by the ex-untouchables who today call themselves

Dalits never reconciled himself with Gandhi, the politician he criticized for being unwilling to tell India “the whole truth,” who may, nevertheless, have been responsible for his elevation to the national position he craved.

Ambedkar had a point if he meant to say that Gandhi’s status as national leader owed something to a tendency to speak less than “the whole truth.” But the Mahatma was more apt to belittle his own mahatmaship than to deny being a politician. So hurling the epithet “Politician!”

against this original, self-created exemplar of leadership—venerated, if imperfectly understood, by most Indians—didn’t take much insight or carry much sting. If Ambedkar was saying that the Mahatma’s insistence on “truth” as his lodestar was self-serving and therefore delusional, was he also saying he’d have admired the national leader more if he let go of that claim? Gandhi may have been a politician, but there were few, if any, like him in his readiness to summon his followers, or himself, to new and more difficult tests. By the summer of 1933 the man described by Nehru as having “

a flair for action” was torn between competing causes, unable to decide whether to focus on a scaled-down campaign of

civil disobedience or a full-throated crusade against untouchability. He could argue that the two causes were “indivisible,” but his movement and the colonial authorities, in their own ways, pushed him to a choice.

The British still held most of his top Congress colleagues in prison, a practical way of forestalling any new wave of resistance. But Gandhi knew that was precisely what the younger, more educated congressmen wanted.

He also knew that the one sure consequence of calling for renewed civil disobedience would be his own reincarceration. First he tried suspending civil disobedience to concentrate on the Harijan cause.

This provoked the Bengali firebrand

Subhas Chandra Bose to write him off as a failure. Next he attempted to split the difference by calling for individual acts of civil disobedience, as opposed to mass resistance. The new tactic was too much for the British, too little for younger Congressmen like Bose and Nehru. When he announced a small march in defiance of a ban on political demonstrations, he was promptly clapped back into Yeravda. In his previous imprisonment, he’d been allowed to work on his latest weekly newspaper inside the jail so long as it was limited to the discussion of the Harijan cause, which was why he called the paper

Harijan

. This time he was treated as an ordinary convict, with no privileges, no paper. Within two weeks he began yet another fast, his third in eleven months, and came close enough to killing himself that he had to be hospitalized. “

Life ceases to interest me if I may not do Harijan work without let or hindrance,” he said.

The colonial authorities offered release on condition he abandon civil disobedience, echoing his stilted legalism in a manner that sounded belittling, even faintly mocking. “

If Mr. Gandhi now feels,” an official statement said, “that life ceases to interest him if he cannot do Harijan work without let or hindrance, the Government are prepared … to set him at liberty at once so that he can devote himself wholly and without restriction to the cause of social reform.” First he rejected the idea of

conditional release; then, released from the hospital unconditionally, he announced he’d not “court imprisonment by offering aggressive civil resistance” for most of the coming year. He’d accept the government’s terms as long as he didn’t have to acknowledge doing so.

He was thus maneuvered into doing what Charles Andrews had urged him to do in the first place, giving way to what he now claimed to be “the breath of life for me, more precious than the daily bread.” He was speaking of “Harijan service,” which in his mind meant persuading caste Hindus to accept Harijans as their social equals. He couldn’t promise to devote himself wholly to that cause until equality was achieved—after all, there was still independence to be won—but he’d do so for the next nine months by touring the country from one end to the other, campaigning for a change of heart by caste Hindus and for funds to be devoted to the cause of “uplift” for his Harijans. Somewhat reluctantly, he thus sentenced himself to becoming a full-time social reformer for that stretch of time.

His commitment was at once a moral obligation and a compromise, an evangelical crusade and a tactical retreat. To many of his followers, it meant he was putting the national movement on hold. To Gandhi himself, it must have seemed the only way forward. His secretary, Mahadev, was in jail. So were Nehru, Patel, Kasturba, even Mirabehn, among thousands of other Congress supporters. His arduous anti-untouchability crusade may have been inadequate in its preparation and follow-up; there may be little proof that it left an enduring impression on the psyches of caste Hindus who turned out by the tens of thousands to hear him (or at least see him).

Ambedkar seldom took note of it;

Dalits today don’t celebrate it; Gandhi biographers pass over it in a few paragraphs. Yet, hurried and improvised as it undoubtedly was, there’s really nothing in Indian annals to which it can be compared. From November 1933 through early August 1934, a period of nine months, Mahatma Gandhi barnstormed strenuously against untouchability from province to province, one dusty town to the next, through the hot season and the rainy season, sometimes on foot from village to village, giving three, four, five speeches a day—six days a week, omitting only Mondays, his “silent day”—mostly to mammoth crowds, drawn by the man rather than his cause. In that time, he traveled more than 12,500 miles by rail, car, and foot, collecting more than 800,000 rupees (equivalent in today’s dollars to about $1.7 million) for his new Harijan fund. By comparison, an American presidential

campaign can be viewed as a cushy, leisurely excursion on a luxury liner.

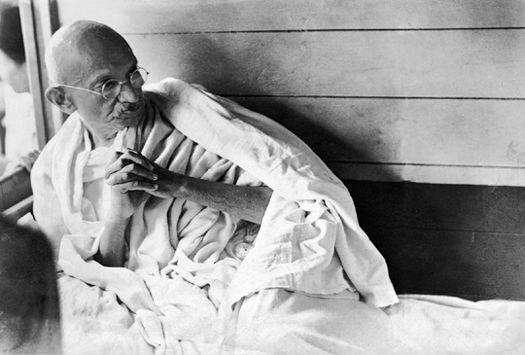

On tour by rail, circa 1934

(photo credit i9.1)

An early conclusion of a British official assigned to keep close tabs on Gandhi’s doings was that the frail old man in the loincloth, coming off two prolonged fasts in the previous ten months, was displaying “amazing toughness.” Soon it became routine for batteries of orthodox Hindus to intercept him at his rallies or along his route, zealously chanting anti-Gandhi slogans and waving black flags. In Nagpur, where the tour started, eggs were thrown from the balcony of a hall in which he was speaking; in Benares, where it ended, orthodox Hindus, called

sanatanists

, burned his picture. A bomb went off in Poona, and an attempt was made to derail the train on which he traveled from Poona to Bombay. At a place called Jasidih in Bihar, his car was stoned. Scurrilous anti-Gandhi pamphlets appeared at many of these places, targeting him as an enemy of Hindu dharma, a political has-been who promised much and failed to deliver, even calling attention to the massages he received from women in his entourage. Here we come upon the first signs of the viral subculture that would spawn his murder fourteen years later.

More generally, the cleavages among Hindus he had anticipated and feared were now out in the open, but he never turned back. Missionaries

travel to lands they deem to be heathen; presenting himself as a Hindu revivalist, Gandhi took his campaign to his own heartland. He didn’t have one set piece, what’s now called a stump speech, but the same themes reappeared in a more or less impromptu fashion. They all led to the same conclusion. If India were ever to deserve its freedom, he preached, untouchability had to go. Yet at many of the rallies, untouchables were segregated in separate holding pens, either because they were afraid to be seen by caste Hindus as overstepping or because none of the local organizers was alive to the contradiction of putting untouchability on display at an anti-untouchability rally.