Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India (54 page)

Read Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India Online

Authors: Joseph Lelyveld

Tags: #Political, #General, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Biography, #South Africa - Politics and government - 1836-1909, #Nationalists - India, #Political Science, #South Africa, #India, #Modern, #Asia, #India & South Asia, #India - Politics and government - 1919-1947, #Nationalists, #Gandhi, #Statesmen - India, #Statesmen

With his chosen “successor,” 1946

(photo credit i11.6)

Later he got closer to the truth, perhaps, when he said of Nehru: “

He has made me captive of his love.”

But now—with the Noakhali Gandhi out of touch and power shifting rapidly into his hands—Nehru, by inclination as well as necessity, was speaking his own language and listening less. The ostensible point of his journey to Srirampur had been to update Gandhi on a resolution he planned to put before the party the next week, further locking it into a process that could lead to

partition and Pakistan; also, Nehru said, it was to urge Gandhi to put Noakhali behind him and return to Delhi so he could be more easily consulted and—this would have gone without saying—privately implored not to stray too far from the emerging party line.

The Mahatma’s appetite for grappling with national issues was tickled, but he wasn’t tempted to return. He said there was still work to be done in Noakhali; by his own reckoning, his mission there would remain

unfinished until the day he died. More compelling was his sense that he’d lost the ability to influence his erstwhile followers, as he’d recently complained in a note to the industrialist

G. D. Birla. “

My voice,” the note said, “carries no weight in the Working Committee … I do not like the shape that things are taking and I can’t speak out.”

Such misgivings, however, didn’t stop him from sending Nehru back with “instructions.” The document, drafted late on Nehru’s last night in Srirampur, pointed in several directions at once.

Basically, it said Gandhi had been right in suggesting the Congress reject the British plan; that now that it had failed to heed his advice, it was stuck with the plan; that therefore it needed an accord with Jinnah giving him “a universally acceptable and inoffensive formula for his Pakistan,” so long as no territories were compelled to be part of it.

The phrase “acceptable and inoffensive” was telling. It pointed in more or less the same direction as Nehru’s unusually dense resolution, which all but smothered its essential acceptance of an unpalatable British formula with a blanket of technicalities, exceptions, and complaints. Between the lines, both Gandhi’s “instructions” and Nehru’s resolution pointed to the quickest deal for independence, on the best available terms, with the fewest possible concessions to the

Muslim League. Obviously, Gandhi meant “acceptable” and “inoffensive” to the Congress and himself, not Jinnah and his followers; he didn’t say how that could be accomplished. On one level, he hadn’t budged from the position he’d taken when Jinnah broke off talks with him two years earlier. On another, he’d shown that he’d do nothing to delay a handover of power even if it involved two recipients instead of one.

Nehru’s resolution was adopted the next week by the

All India Congress Committee by something less than acclamation, a vote of 99–52.

When a member asked to know Gandhi’s advice, Kripalani snapped that it was “irrelevant at this stage,” not bothering to cite the woolly “instructions” the Mahatma had written out for Nehru, who’d flown to East Bengal, it seems likely, partly to ensure that Gandhi wouldn’t come out on the other side. Gandhi himself had been pleased to paper over his most recent breach with the leadership. “

I suggest frequent consultations with an old, tried servant of the nation,” he’d written in a fond farewell note to Nehru.

Just two days later, on the second day of the new year, he pulled up stakes in Srirampur and left on his walking tour of Noakhali, with one hand

clutching a bamboo staff and the other resting on Manu’s shoulder. He was barefoot and would continue without sandals every step of the way for the next two months. In the mornings, the pilgrim’s feet were sometimes numbed by cold; on one occasion at least, they bled. Nightly they were pressed and massaged with oil. Srirampur’s Muslim villagers lined the path that circled Darikanath pond, a well-stocked fishery, that first morning; a crowd of about a hundred walked in his footsteps, with a detachment of eight armed police and at least as many reporters. The next morning headlines in Calcutta’s Indian-owned, pro-Congress, English-language daily, the

Amrita Bazar Patrika

, heralded the launch:

GANDHIJI’S EPIC

TOUR BEGINSH

ISTORIC

M

ARCH

T

HROUGH

P

ADDY

F

IELDS

AND

G

REEN

G

ROVESGANDHIJI LIKELY

TO WORK

MIRACLE

The newspaper kept the tour on its front page every day but one for the next six weeks, conveying the authorized versions of Gandhi’s nightly prayer meeting talks. Too early by a matter of decades to have made great television, it faded as a big story elsewhere. So the loneliness and vicissitudes of the trek never really registered beyond Bengal. After the first few days, the crowds dwindled, with Muslims once again conspicuous by their absence. This time there could be little doubt that elements in the Muslim League were promoting a boycott. In the second month, handbills started appearing urging Gandhi to focus on Bihar, amplifying the theme of most Muslim officials he encountered. “

Remember Bihar,” one said. “We’ve warned you many times. Go back. Otherwise, you’ll be sorry.” Obviously meant for his eyes, another said: “Give up your hypocrisy and accept Pakistan.”

On some mornings, Gandhi’s companions would find that human feces had been deposited, dumped, or spread on paths he could be expected to walk. On his way to a village called Atakora, the old man himself stooped over and started scooping up excrement with dried leaves. A flustered Manu protested that he was putting her to shame. “

You don’t know the joy it gives me,” the Mahatma, now seventy-seven, replied.

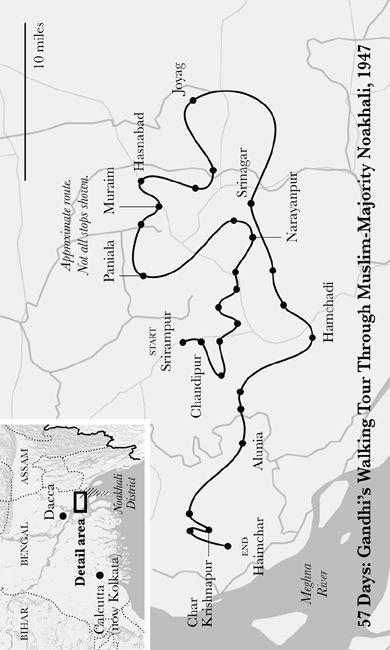

In fifty-seven days, he visited forty-seven villages in Noakhali and a neighboring district called Tipperah, trudging 116 miles, barefoot all the way, in order to touch Muslims’ hearts through a personal demonstration of his own openheartedness and simplicity. He called it a “pilgrimage.” Sometimes he said it was a “penance,” for the slaughter Hindus and Muslims had recently inflicted on each other, or his own failure to end it. He greeted every Muslim he passed, even where most of them stolidly refrained from responding. Only three times, in all those days and weeks, all those villages, was he invited to stay in a Muslim home. His followers prefabricated a tidy hut of bamboo panels to be disassembled on a daily basis and, with each new village, reassembled for his comfort. He complained it was “palatial.” When he learned it took seven porters to carry his collapsible shelter, he refused to sleep in it, insisting it be converted into a dispensary. If Muslims stayed away from his prayer meetings, he pursued them in their houses and huts. In each new village, Manu was dispatched to call on Muslim women in seclusion. Sometimes she managed to persuade them to meet the Mahatma,

sometimes doors were slammed in her face. When young Muslim Leaguers came to his meetings to heckle, he turned back their sharp questions with calm, reasoned replies.

January 1947, bones of Noakhali victims on display for the Mahatma

(photo credit i11.7)

“How did your ahimsa work in Bihar?” he was pointedly asked in a village called Paniala.

“It didn’t work at all,” he replied. “

It failed miserably.”

“

What in your opinion is the cause of the communal riots?” another asked.

“The idiocy of both communities,” said the Mahatma.

Twice in nine weeks, he’s brought to exposed human remains left over from the killings. The first time, on November 11, a stray dog leads him to the skeletons of the members of a single Hindu household; then, on January 11, he passes by a

doba

, or pond, that has finally been dragged to retrieve the bodies of Hindus killed in the earliest and ugliest of these pogroms at Karpara.

The Mahatma moved on briskly. “It is useless to think about those

who are dead,” he said. His aim was less to console bereaved Hindus than to stiffen their spines while touching the hearts of Muslims who’d looked away from the carnage, or even approved it.

He could only demonstrate his good intentions “by living and moving among those who do not trust me,” he said. So every morning, he trudged on, regardless of the reception he encountered. His followers sang religious songs, always including one by Tagore with a Bengali poem called

“Walk Alone” as its lyric. Occasionally there was a welcome, occasionally a large crowd. In the fourth week, at a village called Muriam, a warm reception from Muslims was orchestrated by a friendly maulana named Habibullah Batari who, if Pyarelal’s account can be accepted, introduced him by saying: “

Our community today suffers from the stigma of shedding the blood of our Hindu brothers. Mahatmaji has come to free us of that stain.” For Gandhi, this was proof of the possibilities before him and the country. But it was hardly an everyday occurrence. At Panchgaon, four days later, he was urged by the head of the local Muslim League to discontinue his prayer meetings because they offended Muslims and, better yet, end his Noakhali tour altogether.

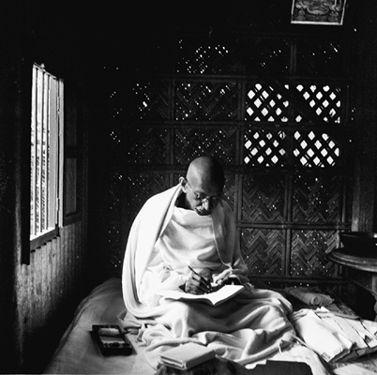

In his mobile hut, November 1946

(photo credit i11.8)

At the prayer meetings, he’d size up his audiences, then draw familiar themes and messages from the repertoire of a lifetime. If seeking to make the point that he and the village workers he brought with him had come not to sit in judgment but to serve, he’d dwell on all that could be done to improve sanitation and the cleanliness of the district’s water. Speaking of lost livelihoods, he’d talk about crafts and what they could do for village uplift. On the fraught, overarching issue of land tenure, he’d say the land belonged to God and those who actually worked it, that reduction in the landlord’s share of crops was therefore only just, with the Gandhian proviso that it had to be accomplished without violence.

The value he upheld most insistently was fearlessness. To insure peace, he said, Muslims and Hindus had to be ready to die. It’s the message he’d given Czechs and European Jews in the previous decade about how to face the Nazis, the idea that a courageous satyagrahi could “melt the heart” of a tyrant. Repeatedly he asked that the police guards Suhrawardy had sent be withdrawn so as not to weaken the example he was hoping to set through his pilgrimage. (The guards never left. Suhrawardy said it was the government’s responsibility to make sure the Mahatma got out of East Bengal alive.)

Early on he talked about martyrdom: “The sacrifice of myself and my companions would at least teach [Hindu women] the art of dying with self-respect. It might open the eyes of the oppressors, too.” To a refugee who asked how he could expect

Hindus to return to villages where they might face attack, he replied: “I do not mind if each and every one of the five hundred families in your area is done to death.” Before arriving in Noakhali, he’d struck a similar note speaking to a trio of Gandhian workers who were planning to precede him: “

There will be no tears but only joy if tomorrow I get the news that all three of you were killed.”

Not infrequently in these months, Gandhi comes across as sounding this extreme, very nearly the fanatic he’d sometimes been accused of being. We may assume it’s a figure of speech, not meant to be taken literally. But even Manu isn’t immune from his determination to teach that his kind of courage in the cause of peace could be—sometimes had to be—as fierce and selfless as any shown on a battlefield.