Great Tales from English History, Book 2

Read Great Tales from English History, Book 2 Online

Authors: Robert Lacey

ROBERT

,

EARL OF ESSEX

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRY VIII

THE QUEENS OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC

SIR WALTER RALEGH

MAJESTY

:

ELIZABETH II AND THE HOUSE OF WINDSOR

THE KINGDOM

PRINCESS

ARISTOCRATS

FORD

:

THE MEN AND THE MACHINE

GOD BLESS HER

!

LITTLE MAN

GRACE

SOTHEBY

’

S

:

BIDDING FOR CLASS

THE YEAR

1000

THE QUEEN MOTHER’S CENTURY

ROYAL:

HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II

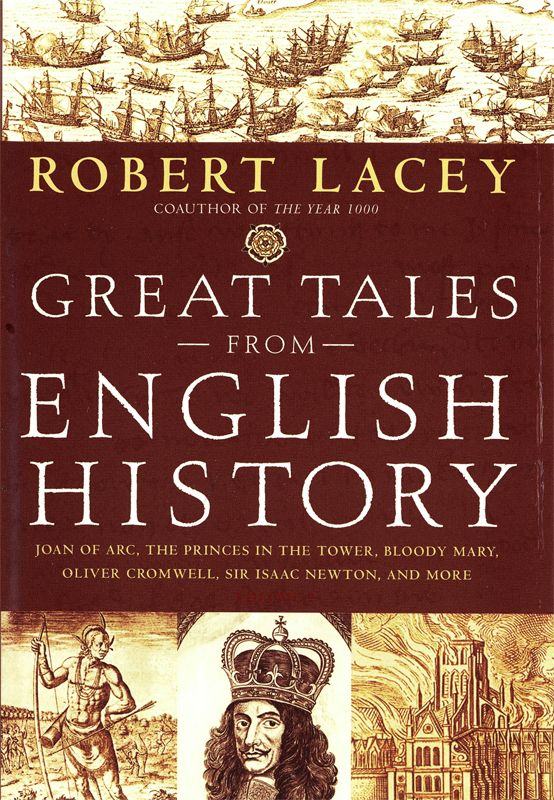

GREAT TALES FROM ENGLISH HISTORY

:

THE TRUTH ABOUT KING ARTHUR

,

LADY GODIVA

,

RICHARD THE LIONHEART, AND MORE

Copyright © 2004 by Robert Lacey

Illustrations and maps © 2004 by Fred van Deelen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First published in Great Britain by Little, Brown and Company, 2004 First United States edition, June 2005

First eBook Edition: November 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-09039-1

FOR SCARLETT

Contents

The Houses of York, Lancaster and Tudor

The Houses of Tudor and Stuart

Map of England and North-west Europe 1387-1688

Introduction: History in Our Heads

1387: Geoffrey Chaucer and the Mother Tongue

1599: The Deposing of King Richard II

1399: ‘Turn Again, Dick Whittington!’

1399: Henry IV and His Extra-Virgin Oil

1415: We Happy Few - the Battle of Azincourt

1429: Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans

1440: A‘Prompter for Little Ones’

1422-61, 1470-1: House of Lancaster: the Two Reigns of Henry VI

1432-85: The House of Theodore

1461-70, 1471-83: House of York: Edward IV, Merchant King

1483: Whodunit? The Princes in the Tower

1485: The Battle of Bosworth Field

1509-33: King Henry VIII’s Great Matter’

1525: Let There be Light’ William Tyndale and the English Bible

1535: Thomas More and His Wonderful‘No-Place’

1533-7: Divorced, Beheaded, Died…

1539-47:… Divorced, Beheaded, Survived

1547-53: Boy King - Edward VI, The Godly Imp’

1553: Lady Jane Grey -The Nine-Day Queen

1553-S: Bloody Mary and the Fires of Smithfield

1557: Robert Recorde and His Intelligence Sharpener

1559: Elizabeth - Queen of Hearts

1585: Sir Walter Ralegh and the Lost Colony

1588: Sir Francis Drake and the Spanish Armada

1605: 5/11: England’s First Terrorist

1611: King James’s‘Authentical’ Bible

1616: ’Spoilt Child’ and the Pilgrim Fathers

1622: The Ark of the John Tradescants

1629: God’s Lieutenant in Earth

1642: ’All My Birds Have Flown’

1642-8: Roundheads V. Cavaliers

1649: Behold the Head of a Traitor!

1653: ’Take Away This Bauble!’

1655: Rabbi Manasseh and the Return of the Jews

1660: Charles II and the Royal Oak

1665: The Village that Chose to Die

1678/9: Titus Oates and the Popish Plot

1685: Monmouth’s Rebellion and the Bloody Assizes

1687: Isaac Newton and the Principles of the Universe

Acclaim for Volume 1 of Robert Layer’s GREAT TALES FROM ENGLISH HISTORY

(see map on

page xii

for battles)

HISTORY IN OUR HEADS

F

OR MOST OF US, THE HISTORY IN OUR HEADS

is a colourful and chaotic kaleidoscope of images — Sir Walter Ralegh laying down

his cloak in the puddle, Isaac Newton watching the apple fall, Geoffrey Chaucer setting off for Canterbury with his fellow

pilgrims in the dappled medieval sunshine. We are not always sure if the stories embodied by these images are entirely true

— or if, in some cases, they are true at all. But they contain a truth, and their narrative power is the secret of their survival

over the centuries. You will find these images in the pages that follow — just as colourful as you remember, I hope, but also

closer to the available facts, with the connections between them just a little less chaotic.

Our very first historians were storytellers — our best historians still are — and in many languages‘story’ and‘history’ remain

the same word. Our brains are wired to make sense of the world through narrative — what came first and what came next — and

once we know the sequence, we can start to work out the how and why. We peer down the kaleidoscope in order to enjoy the sparkling

fragments, but as we

turn it we also look for the reassuring discipline of pattern. We seek to make sense of the scanty remnants of the lives that

preceded ours on the planet.

The lessons we derive from history inevitably resonate with our own code of values. When we go back to the past in search

of heroes and heroines, we are looking for personalities to inspire and comfort us, to confirm our view of how things should

be. That is why every generation needs to rewrite its history, and if you are a cynic you may conclude that a nation’s history

is simply its own deluded and self-serving view of its past.

Great Tales from English History

is not cynical: it is written by an eternal optimist — albeit one who views the evidence with a sceptical eye. In these books

I have endeavoured to do more than just retell the old stories; I have tried to test the accuracy of each tale against the

latest research and historical thinking, and to set them in a sequence from which meaning can emerge.

The first volume of

Great Tales from English History

showed how the beginnings of English history were shaped and reshaped by invasion — Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Danish, Norman. And

that was just the armies. The Venerable Bede, our first English historian, described the invasion of the new religion, which,

in AD 597, so scared King Ethelbert of Kent that he insisted on meeting the Christian missionaries out of doors, lest he be

trapped by their alien magic. We met Richard the Lionheart, England’s French-speaking hero-king, who spent only six months

living in England and adopted our Turkish-born patron saint, St George, while he was fighting the Crusades. Then, as now,

we discovered,

some of the things that most define England have come from abroad. Magna Carta was written in Latin, and Parliament, our national‘talking-place’,

derives its name from the French.

This volume opens in the aftermath of another invasion — by a black rat with an infected flea upon its back. In 1348 and in

a succession of subsequent outbreaks, the Black Death wiped out nearly half of England’s five million people. Could a society

undergo a more ghastly trauma? Yet there were dividends from that disaster: a smaller workforce meant higher wages; fewer

purchasers per acre brought property prices down. In 1381 the leaders of the so-called’Peasants’ Revolt’ with which we concluded

the earlier volume were men of a certain substance. They were taxpayers, the solid, middling folk who have been the backbone

of all the profound revolutions of history. Later in this volume we will see their descendants enlisting in an army that would

behead a king.

Changing economic circumstances have a way of shaping beliefs, and so it was in the fourteenth century. John Wycliffe told

the survivors of plague-stricken England that they should seek a more direct relationship with their God, read His word in

their own language, and not rely upon the priest. Wycliffe’s persecuted followers, the Lollards, or‘mumblers’, as they were

called by their detractors, in derision of their privately mouthed prayers, would provide a persistent underground presence

in the century and a half that followed. If invasion was the theme of the previous volume, dissent — spiritual, personal and,

in due course, political — will take centre stage in the pages that follow.