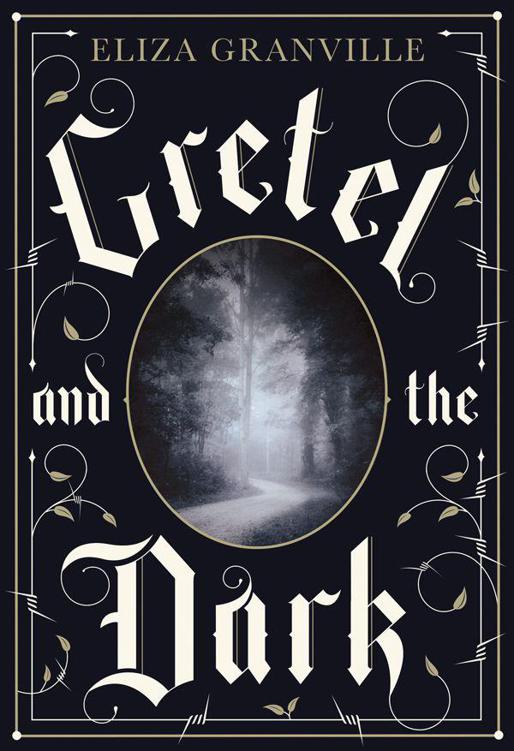

Gretel and the Dark

Read Gretel and the Dark Online

Authors: Eliza Granville

Eliza GranvilleGRETEL AND THE DARK

It is many years before the Pied Piper comes back for the other children. Though his music has been silenced, still thousands are forced to follow him, young, old, large, small, everyone … even the ogres wearing ten-league boots and cracking whips, even their nine-headed dogs. We are the rats in exodus now and the Earth shrinks from the touch of our feet. Spring leaves a bitter taste. All day, rain and people fall; all night, nixies wail from the lakes. The blood-coloured bear sniffs at our heels. I keep my eyes on the road, counting white pebbles, fearful of where this last gingerbread trail is leading us.

Has the spell worked? I think so: coils of mist lap at our ankles, rising to mute all sounds, swallowing everyone around us whole. When the moment comes, we run blind, dragging the Shadow behind us, stopping only when my outstretched hand meets the rough bark of pine trunks. One step, two, and we’re inside the enchanted forest, the air threaded with icy witch-breaths. The day collapses around us. Phantom sentries swoop from the trees demanding names but our teeth guard the answers so they turn away, flapping eastward in search of the cloud-shrouded moon. Roots coil, binding us to the forest floor. We crouch in a silence punctuated by the distant clatter of stags shedding their antlers.

We wake, uneaten. Every trace of mist has been sucked away by the sun. The landscape seems empty. We haven’t come

far: I can see where the road runs but there’s no sign of anything moving along it. It’s quiet until a cuckoo calls from deep within the trees.

‘Listen.’

‘Kukułka,’ he says, shielding his eyes as he searches the topmost branches.

‘Kuckuck,’ I tell him. He still talks funny. ‘She’s saying “Kuckuck”!’

He gives his usual jerky shrug. ‘At least we’re free.’

‘Only if we keep moving. Come on.’

The Shadow whimpers but we force it upright and, supporting it between us, move slowly along the edge of the trees until we come to fields where ravens are busy gouging out the eyes of young wheat. Beyond, newly buried potatoes shiver beneath earth ridges. Cabbages swell like lines of green heads. When we kneel to gnaw at their skulls, the leaves stick in our throats.

We carry on walking, feet weighted by the sticky clay, until the Shadow crumples. I pull at its arm. ‘It’s not safe here. We must go further. If they notice we’ve gone –’ Keep going. We have to keep going. Surely sooner or later kindly dwarves or a soft-hearted giant’s wife must take pity on us. But fear has become too familiar a companion to act as a spur for long. Besides, we’re carrying the Shadow now. Its head lolls, the wide eyes are empty and its feet trail behind, making two furrows in the soft mud. It could be the death of us.

‘We should go on alone.’

‘No,’ he pants. ‘I promised not to leave –’

‘I didn’t.’

‘Then you go. Save yourself.’

He knows I won’t go on without him. ‘No good standing

here talking,’ I snap, hooking my arm under the Shadow’s shoulder and wondering how something thin as a knife blade can be so heavy.

Another rest, this time perched on the mossy elbow of an oak tree, attempting to chew a handful of last year’s acorns. Only the sprouted ones stay down. The Shadow lies where we dropped it, facing the sky, though I notice its eyes are completely white now. Without warning it gives a cry, the loudest noise it’s ever made, followed by a gasp and a long, juddering out-breath. I finish spitting out the last of the acorns. The Shadow isn’t doing its usual twitching and jumping; it doesn’t even move when I push my foot into its chest. After a moment, I gather handfuls of oak leaves and cover its face.

He tries to stop me. ‘Why are you doing that?’

‘It’s dead.’

‘No!’ But I can see the relief as he pulls himself on to his knees to check. ‘After enduring so much, still we die like dogs …

pod płotem

… next to a fence, under a hedge.’ He closes the Shadow’s eyes. ‘

Baruch dayan emet

.’ It must be a prayer: his lips go on moving but no sound emerges.

‘But we’re not going to die.’ I tug at his clothes. ‘Shadows never last long. You always knew it was hopeless. Now we can travel faster, just you and me.’

He shakes me off. ‘The ground here is soft. Help me dig a grave.’

‘Won’t. There’s no time. We have to keep going. It’s already past midday.’ I watch him hesitate. ‘Nothing will eat a shadow. There’s no meat on it.’ When he doesn’t move I trudge away, forcing myself not to look back. Eventually he catches up.

The path continues to weave between field and forest. Once, we catch sight of a village but decide it’s still too near the black

magician’s stronghold to be safe. Finally, even the sun starts to abandon us and our progress slows until I know we can drag ourselves no further. By now the forest has thinned; before us stretches an enormous field with neat rows as far as the eye can see. We’ve pushed deep between the bushy plants before I realize it’s a field of beans.

‘What does it matter?’ he asks wearily.

‘Cecily said you go mad if you fall asleep under flowering beans.’

‘No flowers,’ he says curtly.

He’s wrong, though. A few of the uppermost buds are already unfurling white petals, ghostly in the twilight, and in the morning it’s obvious we should have pressed on, for hundreds of flowers have opened overnight, dancing like butterflies on the breeze, spreading their perfume on the warming air.

‘Let me rest for a bit longer,’ he whispers, cheek pressed against the mud, refusing to move, not even noticing a black beetle ponderously climbing over his hand. ‘No one will find us here.’

His bruises are changing colour. Where they were purple-black, now they are tinged with green. When he asks for a story, I remember what Cecily told me about two children who came out of a magic wolf-pit. They had green skin, too.

‘It was in England,’ I tell him, ‘at harvest-time, a very long time ago. A boy and a girl appeared suddenly, as if by magic, on the edge of the cornfield. Their skin was bright green and they wore strange clothing.’ I look down at myself and laugh. ‘When they spoke, nobody could understand their fairy language. The harvesters took them to the Lord’s house, where they were looked after, but they would eat nothing at all, not

a thing, until one day they saw a servant carrying away a bundle of beanstalks. They ate those, but never the actual beans.’

‘Why didn’t they eat the beans like anyone else?’

‘Cecily said the souls of the dead live in the beans. If you ate one you might be eating your mother or your father.’

‘That’s plain silly.’

‘I’m only telling you what she said. It’s a true story but if you don’t want me to –’

‘No, go on,’ he says, and I notice in spite of his superior tone he’s looking uneasily at the bean flowers. ‘What happened to the green children?’

‘After they ate the beanstalks they grew stronger and learned to speak English. They told the Lord about their beautiful homeland where poverty was unknown and everyone lived for ever. The girl said that while playing one day they’d heard the sound of sweet music and followed it across pasture land into a dark cave –’

‘Like your story of the Pied Piper?’

‘Yes.’ I hesitate, remembering that in Cecily’s story the boy died and the little girl grew up to be an ordinary wife. ‘I don’t remember the rest.’

He’s silent for a moment, then looks at me. ‘What are we going to do? Where can we go? Who can we turn to? Nobody has ever helped us before.’

‘They said help was coming. They said it was on its way.’

‘Do you believe it?’

‘Yes. That’s why we must keep walking towards them.’ Beneath the bruises, his face is chalk-white again. His arm doesn’t look right and he winces whenever he tries to move it. There’s fresh blood at the corners of his mouth. And suddenly I’m so

angry I might explode. ‘I wish I could kill him.’ My fists clench so hard my nails dig in. I want to scream and spit and kick things. He continues to look questioningly at me. ‘I mean, the man who started it all. If it hadn’t been for him –’

‘Didn’t you hear what everyone was whispering? He’s already dead.’ Again, the small shrug. ‘Anyway, my father said if it hadn’t been him there’d have been someone else just like him.’

‘And maybe then it would have been someone else here, not us.’

He smiles and squeezes my hand. ‘And we would never have met.’

‘Yes, we would,’ I say fiercely. ‘Somehow, somewhere – like in the old stories. And still I wish it could have been me that killed him.’

‘Too big,’ he says weakly. ‘And too powerful.’

I knuckle my eyes. ‘Then I wish I’d been even bigger. I would have stepped on him or squashed him like a fly. Or I wish he’d been even smaller. Then I could have knocked him over and cut off his head or stabbed him in the heart.’ We sit in silence for a while. I think about all the ways you could kill someone shrunk to Tom Thumb size. ‘We ought to go now.’

‘Let me sleep.’

‘Walk now. Sleep later.’

‘All right. But first tell me a story – one of your really long ones – about a boy and a girl who kill an ogre.’

I think for a moment. None of my old stories seem bad enough until I realize there were other circumstances in which an ogre really could be killed. Thanks to Hanna, I know where. And I even know when. All of a sudden, I’m excited. ‘Once upon a time,’ I begin, but see immediately I can’t start that way. It

isn’t that sort of tale. He’s still holding my hand. I give it a sharp tug. ‘Get up. From now on I shall only tell you my story while we’re walking. The moment you stop, I shan’t say another word.’