Grit (21 page)

Authors: Angela Duckworth

At its core, the idea of purpose is the idea that what we do matters to people other than ourselves.

A precocious altruist like Alex Scott is an easy-to-fathom example of other-centered purpose.

So is art activist Jane Golden, the grit paragon we met in chapter 6. Interest in art led Jane to become a muralist in Los Angeles after graduating from college. In her late twenties, Jane was diagnosed with lupus and told she didn’t have long to live. “The news came as such a shock,” she told me. “It gave me a

new perspective on life.” When Jane recovered from the disease’s most acute symptoms, she realized she would outlive the doctors’ initial predictions, but with chronic pain.

Moving back to her hometown of Philadelphia, she took over a small anti-graffiti program in the mayor’s office and, over the next three decades, grew it into one of the largest public art programs in the world.

Now in her late fifties, Jane continues to work from early morning to late in the evening, six or seven days a week. One colleague likens working with her to running a campaign office the night before an election—except

Election Day never comes. For Jane, those hours translate into more murals and programs, and that means more opportunities for people in the community to create and experience art.

When I asked Jane about her lupus, she admitted, matter-of-factly, that pain is a constant companion. She once told a journalist: “There are moments when I cry. I think I just can’t do it anymore, push that boulder up the hill. But feeling sorry for myself is pointless,

so I find ways to get energized.” Why? Because her work is interesting? That’s only the beginning of Jane’s motivation. “Everything I do is in a spirit of service,” she told me. “I feel driven by it.

It’s a moral imperative.” Putting it more succinctly, she said: “Art saves lives.”

Other grit paragons have top-level goals that are purposeful in less obvious ways.

Renowned wine critic Antonio Galloni, for instance, told me: “An

appreciation for wine is something I’m passionate about sharing with other people. When I walk into a restaurant, I want to see a

beautiful bottle of wine on every table.”

Antonio says his mission is “to help people understand their own palates.” When that happens, he says, it’s like a lightbulb goes off, and he wants “to make

a million lightbulbs go off.”

So, while interest for Antonio came first—his parents owned a food and wine shop while he was growing up, and he “was always fascinated by wine, even at a young age”—his passion is very much enhanced by the idea of helping other people: “I’m not a brain surgeon, I’m not curing cancer. But in this one small way, I think I’m going to make the world better. I wake up every morning with a

sense of purpose.”

In my “grit lexicon,” therefore,

purpose

means “the intention to contribute to the

well-being of others.”

After hearing, repeatedly, from grit paragons how deeply connected they felt their work was to other people, I decided to analyze that connection more closely. Sure, purpose might matter, but how

much

does it matter, relative to other priorities? It seemed possible that single-minded focus on a top-level goal is, in fact, typically more

selfish

than

selfless

.

Aristotle was among the first to recognize that there are at least two ways to pursue happiness. He called one “eudaimonic”—in harmony with one’s good (

eu

) inner spirit (

daemon

)—and the other “hedonic”—aimed at positive, in-the-moment, inherently self-centered experiences. Aristotle clearly took a side on the issue, deeming the hedonic life primitive and vulgar, and upholding

the eudaimonic life as noble and pure.

But, in fact, both of these two approaches to happiness have very deep evolutionary roots.

On one hand, human beings seek pleasure because, by and large,

the things that bring us pleasure are those that increase our chances of survival. If our ancestors hadn’t craved food and sex, for example, they wouldn’t have lived very long or had many offspring. To some extent, all of us are, as Freud put it, driven by the “

pleasure principle.”

On the other hand, human beings have

evolved to seek meaning and purpose. In the most profound way, we’re social creatures. Why? Because the drive to connect with and serve others

also

promotes survival. How? Because people who cooperate are more likely to survive than loners. Society depends on stable interpersonal relationships, and society in so many ways keeps us fed, shelters us from the elements, and protects us from enemies. The desire to connect is as basic a human need as our appetite for pleasure.

To some extent, we’re

all

hardwired to pursue both hedonic and eudaimonic happiness. But the

relative

weight we give these two kinds of pursuits can vary. Some of us care about purpose much more

than we care about pleasure, and vice versa.

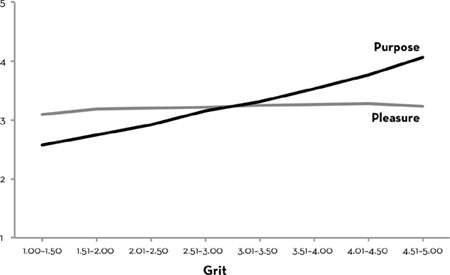

To probe the motivations that underlie grit, I recruited sixteen thousand American adults and asked them to complete the Grit Scale. As part of a long supplementary questionnaire, study participants read statements about

purpose

—for instance, “What I do matters to society”—and indicated the extent to which each applied to them. They did the same for six statements about the importance of

pleasure

—for instance, “For me, the good life is the pleasurable life.” From these responses, we generated scores ranging from 1 to 5 for their orientations to purpose and pleasure, respectively.

Below, I’ve plotted the data from this large-scale study. As you can see, gritty people aren’t monks, nor are they hedonists. In terms of pleasure-seeking, they’re just like anyone else; pleasure is moderately important no matter how gritty you are. In sharp contrast, you can see that grittier people are

dramatically

more motivated than others to seek a meaningful, other-centered life. Higher scores on purpose correlate with

higher

scores on the Grit Scale.

This is not to say that all grit paragons are saints, but rather, that most gritty people see their ultimate aims as deeply connected to the world beyond themselves.

My claim here is that, for most people, purpose is a tremendously powerful source of motivation. There may be exceptions, but the rarity of these exceptions proves the rule.

What am I missing?

Well, it’s unlikely that my sample included many terrorists or serial killers. And it’s true that I haven’t interviewed political despots or Mafia bosses. I guess you could argue that I’m overlooking a whole population of grit paragons whose goals are purely selfish or, worse, directed at harming others.

On this point, I concede. Partly. In theory, you can be a misanthropic, misguided paragon of grit. Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler, for instance, were most certainly gritty. They also prove that the idea of purpose can be perverted. How many millions of innocent people have

perished at the hands of demagogues whose

stated

intention was to contribute to the well-being of others?

In other words, a genuinely positive, altruistic purpose is not an absolute requirement of grit. And I have to admit that, yes, it is possible to be a gritty villain.

But, on the whole, I take the survey data I’ve gathered, and what paragons of grit tell me in person, at face value. So, while interest is crucial to sustaining passion over the long-term, so, too, is the desire to connect with and help others.

My guess is that, if you take a moment to reflect on the times in your life when you’ve really been at your best—when you’ve risen to the challenges before you, finding strength to do what might have seemed impossible—you’ll realize that the goals you achieved were connected in some way, shape, or form to the

benefit of other people

.

In sum, there may be gritty villains in the world, but my research suggests there are many more gritty heroes.

Fortunate indeed are those who have a top-level goal so consequential to the world that it imbues everything they do, no matter how small or tedious, with significance. Consider the parable of the bricklayers:

Three bricklayers are asked: “What are you doing?”

The first says, “I am laying bricks.”

The second says, “I am building a church.”

And the third says, “I am building the house of God.”

The first bricklayer has a job. The second has a career. The third has a calling.

Many of us would like to be like the third bricklayer, but instead identify with the first or second.

Yale management professor Amy Wrzesniewski has found that people have no trouble at all telling her

which of the three bricklayers

they identify with. In about equal numbers, workers identify themselves as having:

a job (“I view my job as just a necessity of life, much like breathing or sleeping”),

a career (“I view my job primarily as a stepping-stone to other jobs”), or

a calling (“My work is one of the most important things in my life”).

Using Amy’s measures, I, too, have found that only a minority of workers consider

their occupations a calling. Not surprisingly, those who do are significantly grittier than those who feel that “job” or “career” more aptly describes their work.

Those fortunate people who do see their work as a calling—as opposed to a job or a career—reliably say “my work makes the world a better place.” And it’s these people who seem most satisfied with their jobs and their lives overall. In one study, adults who felt their work was a calling missed at least a third fewer days of work

than those with a job or a career.

Likewise, a recent

survey of 982 zookeepers—who belong to a profession in which 80 percent of workers have college degrees and yet on average earn a salary of $25,000—found that those who identified their work as a calling (“Working with animals feels like my calling in life”) also expressed a deep sense of purpose (“The work that I do makes the world a better place”). Zookeepers with a calling were also more willing to sacrifice unpaid time, after hours, to care for sick animals. And it was zookeepers with a calling who expressed a sense of moral duty (“I have a moral obligation to give my animals the best possible care”).

I’ll point out the obvious: there’s nothing “wrong” with having no professional ambition other than to make an honest living. But most of us yearn for much more. This was the conclusion of journalist Studs Terkel, who in the 1970s interviewed more than a hundred working adults in all sorts of professions.

Not surprisingly, Terkel found that only a small minority of workers identified their work as a calling. But it wasn’t for lack of wanting. All of us, Terkel concluded, are looking for “daily meaning as well as daily bread . . . for a sort of life rather than a

Monday through Friday sort of dying.”

The despair of spending the majority of our waking hours doing something that lacks purpose is vividly embodied in the story of Nora Watson, a twenty-eight-year-old staff writer for an institution publishing health-care information: “Most of us are looking for a calling, not a job,” she told Terkel. “There’s nothing I would enjoy more than a job that was so meaningful to me that I brought it home.” And yet, she admitted to doing about two hours of real work a day and spending the rest of the time pretending to work. “I’m the only person in the whole damn building with a desk facing the window instead of the door. I just turn myself around from all that I can.

“

I don’t think I have a calling—at this moment—except to be me,” Nora said toward the end of her interview. “But nobody pays you for being you, so I’m at the Institution—for the moment. . . .”

In the course of his research, Terkel did meet a “happy few who

find a savor in their daily job.” From an outsider’s point of view, those with a calling didn’t always labor in professions more conducive to purpose than Nora. One was a stonemason, another a bookbinder. A fifty-eight-year-old garbage collector named Roy Schmidt told Terkel that his job was exhausting, dirty, and dangerous. He knew most other occupations, including his previous office job, would be considered more attractive to most people. And yet, he said: “I don’t look down on my job in any way. . . .

It’s meaningful to society.”

Contrast Nora’s closing words with the ending of Roy’s interview: “I was told a story one time by a doctor. Years ago, in France . . . if you didn’t stand in favor with the king, they’d give you the lowest job, of cleaning the streets of Paris—which must have been a mess in those days. One lord goofed up somewhere along the line, so they put him in charge of it. And he did such a wonderful job that he was commended for it. The worst job in the French kingdom and he was patted on the back for what he did. That was the first story I ever heard about garbage where it really

meant

something.”

In the parable of the bricklayers, everyone has the same occupation, but their subjective experience—how they themselves

viewed

their work—couldn’t be more different.

Likewise, Amy’s research suggests that callings have little to do with formal job descriptions. In fact, she believes that just about

any

occupation can be a job, career, or calling. For instance,

when she studied secretaries, she initially expected very few to identify their work as a calling. When her data came back, she found that secretaries identified themselves as having a job, career, or calling in equal numbers—just about the same proportion she’d identified in other samples.