Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny (30 page)

Read Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny Online

Authors: Marlo Thomas

Jon:

I think that’s absolutely true. We spend so much time on our show trying not to be explicit—but to be

clear

. We try hard to process the material and put it back out there as comedy. But intent is really an important part of it.

Marlo:

And you’re obviously succeeding.

Time

magazine named you one of the most influential people in the country. That had to surprise you.

Jon:

Listen, we do a show that’s about media culture. So I’m never surprised when the media responds that way. It’s like they’re saying, “This man is making fun of us. He’s chosen a very good subject to make fun of. He must be very important.” By considering it as flattery, they elevate

themselves

. I think that’s what the media does. And in the process, we sort of become outsized in whatever they think our influence is.

Marlo:

Still, did you ever imagine that you would have this kind of impact?

Jon:

No, none of this ever seemed possible to me. Even when I told my family what I was doing, there was this sense of “For

what

?”

Marlo:

So what was the lure?

Jon:

It was a language and a rhythm that I thought I understood. It’s like music, you know? You hear it and you feel like, “Yeah, man, that makes sense to me.” You know how some musicians can play by ear? I felt like I had that—like there was a certain “comedy by ear” that I knew how to do. And producing our show is somewhat of a musical process. The most important time for us is between rehearsal and the show, when the song is rewritten to sound a little bit better.

Marlo:

It’s such a kick to watch you on your show, especially when the camera catches you trying not to crack up at something that’s going on. Which makes me want to know: What do

you

find uncontrollably funny? What gets to your funny bone?

Jon:

Sadly, what I love most is when something bombs. Watching the bomb. Loving the bomb.

Marlo:

I love bombs, too. Why is that?

Jon:

Having worked in the clubs for so long is sort of like being a magician for a lot of years—you know all the tricks. So I always found it funny when I was bombing, or one of my friends was bombing. It’s something that’s different—like being caught in a sudden snowstorm.

Marlo:

And if it happens on your show?

Jon:

I enjoy it the most when things go wrong on the show. I relish it. It’s reminds me that “Oh, right, this isn’t neurosurgery.” Like, we’re making jokes about, you know, the Elmo puppet that we re-jiggered to be a Guantánamo detainee, and the beard accidentally comes off. Now, that’s funny.

Because, inherently, we’re like the Little Rascals: We’re just a bunch of idiots in the backyard putting on a show.

I

t is not possible to think about my childhood without thinking about St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Although, like any hospital, it shoulders its share of sadness, St. Jude is also about laughter. Laughter built the place.

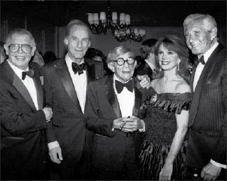

Getting ready to go on, backstage at “The Shower of Stars”

—with Dad, Frank Sinatra and Jerry Lewis.

Dad raised the early funds to build St. Jude from benefit concerts he gave, both on his own and with his pals from the world he knew best—nightclubs. Milton Berle, Bob Hope, George Burns, Sid Caesar, Jack Benny, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Sammy Davis, Jr. Even young Elvis.

Frank did so many of these events that there is a floor at St. Jude named for him. My father called these fund-raising galas “The Shower of Stars,” and they carried a message of hope for the most helpless of all—little children with hopeless diseases.

My father began to build his dream of St. Jude by making a simple sketch of the hospital on a piece of cardboard that came from the cleaners with his shirts. Talk about low-tech. He showed the drawing to every potential donor he could find, but mainly to the Lebanese community, encouraging them to build a place of hope for America’s children, in gratitude to this country for embracing their immigrant parents.

In 1983, the U.S. Congress voted unanimously to award my father with the Congressional Gold Medal for his work as founder of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Ronald Reagan presented it at the White House. A proud day for our family.

But it was his passion that sold it. He lived and breathed the hospital. Dad talked so much about St. Jude when we were growing up that Terre, Tony and I thought he was one of our uncles.

His belief that he could accomplish this is astounding—that a poor kid from Toledo, with one year of high school, a nightclub comedian, would be able to build a world-renowned cancer research hospital. Where does that kind of chutzpah come from?

Same place his humor came from—his immigrant childhood, where no one in his poor neighborhood ever went to a doctor. Dad’s mother gave birth to all ten of her children without a doctor. Children he knew and played with died of influenza and rodent bites. He saw firsthand the inequity of poor health care and was galvanized by the experience. He was going to fix it. And he used his gift of laughter to pay for it.

He named the hospital after St. Jude, patron saint of hopeless causes, to whom he’d prayed when his budding performing career had stalled.

Give me a sign to help me find my way in life, and someday I’ll build a shrine in your name

. He soon found fame, and kept his promise. And he built the hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, because he’d once read a news item about an eight-year-old black child in the South who was riding his bicycle and was struck by a car. But no emergency room in the area would take him, and he died. My father carried that clipping in his wallet for years.

When I became

That Girl

in 1966, Dad called me his “bonus kid,” because, whenever he was unable to attend a St. Jude event, he’d send me to take his place, to pick up a check or make a speech on behalf of the hospital.

At Phil’s and my wedding, Dad clinked his glass and said, “Today, I haven’t lost a daughter. I’ve gained a fund-raiser.” Everyone laughed. He did, too. But he wasn’t kidding. He knew he had just acquired another

bonus kid

.

The two “bonus kids” on their wedding day.

Gloria Steinem, who has raised millions of dollars for every form of civil rights, for candidates across the country and for a myriad of causes she believes in, calls fund-raising “the second oldest profession in the world.” It’s a funny line, but somehow it rings true.

After my father died, I came to realize something that I’m sure everyone who has ever lost someone they loved has learned. And that is—love endures. Even years later, the love remains as before. It doesn’t diminish. It doesn’t divert. It endures, intact.

Then I found out something else. Friendship endures, too. A few months after Dad died, there was a benefit for St. Jude, and I got the news that Bob Hope was flying from L.A. to New York to emcee the event. All through the years, Dad had always called Bob and all of his friends—personally—to ask them to perform at these fund-raisers. But Bob, the emeritus of all things funny, was now doing this without a call from Dad. I was very touched, and phoned Bob to thank him.

“I can’t tell you how moved I am,” I said.

“Are you kidding?” Bob said. “I love Danny.”

Maybe his pal was gone, but their friendship was very much alive.

My siblings and I had never intended to carry the torch of St. Jude. In fact, Dad had been quite clear to us that the work of the hospital would not be our burden to carry after he was gone. We accepted that, and I think each of us was relieved. St. Jude had taken the second half of Dad’s life to build and maintain, and with him gone, the responsibility would be even greater.

Friendship endures. “The Boys”—Milton, Sid, George and Jan—continued to attend St. Jude dinners even after Dad was gone.

Terre, Tony and I followed Dad’s heart to St. Jude.

But soon after he died, Terre, Tony and I thought we should go to Memphis to talk to everyone at the hospital, and let them know that we would be there if they needed us. They had all worked so closely with Dad, been inspired by him, and his death was as much of a shock to them as it was to us. He hadn’t been ill, and had just been with them two days before, celebrating the hospital’s 29th anniversary.

When I got to the driveway at the hospital, with the fifteen-foot statue of St. Jude standing tall at the entrance, I sat in the car, paralyzed. I didn’t want to go inside. It was all too fresh. I also didn’t want to cry in front of the children or their parents. They had enough of their own heartache.

So I pulled myself together and went inside. In the lobby, a party was going on. There was ice cream and cake. Confetti. Balloons. And the happy clamor of children running around in party hats.

“Whose birthday is it?” I asked the nurse.

“Oh, it’s not a birthday party,” she said. “It’s an off-chemo party.”

I had never seen anything like this before. Here were all these little children celebrating and deriving strength from one child’s turn for the better, with their parents and grandparents standing by with tears in their eyes. If this child could make it, maybe their beloved child would, too.

In that moment, I breathed in what my father had been holding in his heart for so many years. I had walked into a place, a community, where hope lived. A place that families had traveled to from all over the country, terrified, carrying death sentences for their babies. I looked around at the fairy-tale murals painted on the walls, at the red wagons, instead of wheelchairs, carrying children down the hallways.

I saw a part of my father that hadn’t been as clear to me before. I had always thought of him as a good man, a philanthropist, but I hadn’t truly understood how deeply personal this was to him. How thoroughly he had given his heart to this place, to these people.

And I knew now that his spirit would always live here.

A few minutes later, a mom brought her little girl over to me.

“Do you know who this lady’s Daddy is?” the mother said to her daughter.

“Yes,” the little girl said.

“Who?” the mom asked.

The little girl proudly answered, “St. Jude.”

In the background I heard the children singing.

“Pack up your bag, get out the door, you don’t need chemo anymore.”

Then I cried.