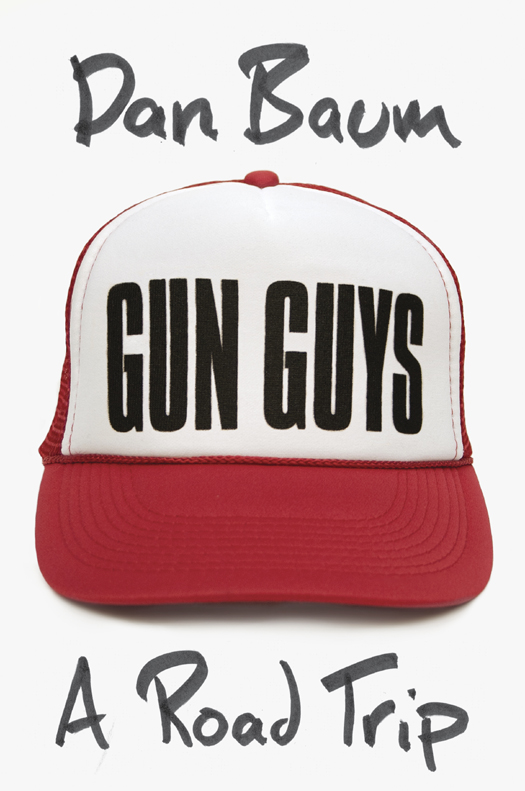

Gun Guys

Authors: Dan Baum

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2013 by Dan Baum

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered

trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of this work were originally published, in a different form, in

Harper’s Magazine

(August 2010) and online as a Kindle Single titled

Guns Gone Wild

(September 2011).

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Steve Lee for permission to reprint an exerpt from “I Like Guns” from

I Like Guns

by Steve Lee (November 2005).

http://ilikeguns.com.au/

. Reprinted by permission of the artist.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Baum, Dan.

Gun guys : a road trip / Dan Baum. — First Edition.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-307-96221-8

1. Firearms owners—United States. 2. Firearms ownership—

United States. 3. Firearms—Social aspects—United States. I. Title.

HV8059.B38 2013

683.400973—dc23 2012028767

Jacket design by Jason Booher

v3.1

For my brother, Andy

I like guns I like the way they look

I like the shiny steel and the polished wood

I don’t care if they’re big or small

If they’re for sale, Hell, I want ’em all

I like guns, I like guns, I like guns

.

…

I don’t really get all the fuss

Why they’re trying to take guns off of us

’Cause I ain’t going to shoot anyone

No one shoots at me ’cause I’ve got a gun

I like guns, I like guns, I like guns

.

—Steve Lee, from his 2010 CD

, I Like

Guns,

which also includes the songs

“I’ll Give Up My Gun,” “Gun Shy

Dog,” and “She Don’t Like Guns”

Dick Cavett: I always wanted a Luger.… The Luger is a sexy object; there is something about that design that is genius and appealing.

Randy Cohen: We don’t have any say in the objects we find seductive.

—On the public radio show

Person Place Thing

, February 15, 2012

W

ithin days of arriving at summer camp, it was clear I’d be forever consigned to right field, ignored by quarterbacks, left jiggling and huffing in the rear during capture the flag. At five, I was the youngest kid ever at Sunapee: a pudgy, overmothered cherub amid a tribe of lean savages. Though I’d begged to follow my brothers to camp, my first week in Bunk 1 was a fog of humiliations large and small. I knew nothing of baseball, tits, or rock and roll; I was quick to tears; I wet the bed. At the end of the first week, I feigned illness for the raw relief of the cool, sympathetic touch of the nurse’s hand on my forehead.

At the edge of the woods loomed a mysterious monolith that was both exciting and vaguely disturbing: a giant white boulder neatly cracked in two. It must have stood five feet high—much taller than my head. The two sides lay just far enough apart that a person could slip between them, and I occasionally saw bigger boys disappearing along the path through the rock—it appeared to be some kind of portal.

One hot day in the second week of camp, Bunk 1’s counselor led the ten of us through. The broken rock faces sparkled in the sunlight, and as we stepped in, a thick mantle of cool air enveloped us. I was disoriented for a moment, as though I’d entered into another dimension. Then the boy in front of me moved, the boy behind me shoved, and we emerged onto a sparsely wooded hillside.

The ground sloped gently away, through white birch saplings, to a wooden platform floating on a sea of ferns. On the platform stood a big man with his fists on his hips. We trotted down the path and clattered aboard. Five urine-stained mattresses lay at the big man’s feet. On the mattresses lay rifles.

Real guns! It was 1961, and, like many kids, I’d seen lots of gunfights on TV. I’d played cowboys with Mattel cap pistols and ambushed friends with primary-colored squirt guns. These rifles, though, were long and serious-looking, their burnished wood warmly reflecting the dappled sunlight. The big man, a crew-cut Rutgers footballer named Hank Hilliard, scooped up a rifle and opened its bolt with a

slick-click

that I felt in my spine. He pointed to the various parts and spoke their names, extending blunt fingers to show how to line up the sights. He sternly repeated the range rules. Then he eenie-meenied five of us to lie on the mattresses and warned us not to touch the rifles until he gave the go-ahead.

I lay on my side, hands clasped between my knees, gazing at the steel barrel two inches in front of my eyes:

MOSSBERG 340 KA NORTH HAVEN

,

CONNECTICUT .22 SHORT LONG OR LONG RIFLE

. I cannot remember the names of my neighbors’ grown children or the seventh dwarf, but to this day I can summon every detail of that rifle and its metallic, smoky, chemical aroma:

guns

.

A cartridge plopped onto the mattress—slender shiny brass with a rounded gray tip. “Pick up your rifles,” Hank boomed, and I hoisted the Mossberg into my arms. Across the far end of the clearing stretched a board fence on which he’d tacked sheets of white paper, each with a black dot at the center. “Open your bolts.” I worked the knob up and back.

Slick-click

. “Load.” I poked the nose of the cartridge into the breech and mashed it forward with my thumb. “Close your bolts.” I pushed the bolt forward and locked it down, the most determined thing I’d ever done. “Aim and fire at will.”

The kid next to me grunted as his rifle popped off. The other three shot nervously in the next two seconds. I ignored them. For days, I’d enviously watched these boys swing bats and tennis rackets, throw spirals, and execute high dives. Now I tuned them out and squeezed the world down to my front sight, a bead-topped post looping tighter and tighter around the black dot. The rifle gave a slight jump against my shoulder and a distant crack. Hank dropped another cartridge on the mattress.

We each shot five bullets and, after an elaborate ceremony of opening bolts and clearing chambers, pelted across the clearing to retrieve our

targets. One kid’s was completely untouched. The rest had two or three holes, the shots scattered widely.

All five of mine were inside the black dot, which I now saw was divided into five concentric rings. Several of my bullet holes touched; one nicked dead center. When I handed the target to Hank, he rocked his head back in surprise. “Damn,” he breathed, touching each hole with a pencil point. “Thirty-six out of fifty.” He handed back the target and gave me my first-ever man-to-man look. “Nice shootin’, Tex.”

Was that my personal Big Bang? Did I get hooked on guns because I discovered I was good at shooting at precisely the moment I was experiencing my first feelings of masculine inadequacy? Is this why I’ve spent a lifetime carrying around an enthusiasm that has made me feel slightly ashamed? Or did I just think the guns were cool and fun, the way other kids fell for fishing rods and ant farms? All I knew at the time was that the rifle range replaced the nurse’s office as my refuge. By day I was forced to trudge through ball sports with the rest of my bunkmates, but when the shadows grew long and we were allowed an elective, I invariably chose riflery. I learned to breathe evenly, listen to my heartbeat, and let the shot go between beats, when the muzzle was steadiest. I learned to place the pad of my index finger against the trigger and squeeze so slowly that the shot came as a surprise. I came to love the snap of the rifle, the rich aroma of burned cordite, the magical geometry of a bullet’s razor-straight trajectory connecting to a tiny, distant point. I even came to enjoy the faint aroma of ancient urine soaked into cotton batting, because that, too, was part of the Camp Sunapee rifle-range experience. Ten targets of twenty-five-plus points won me a tiny bronze Pro-Marksman medal that first summer and a National Rifle Association patch to sew on my melton wool camp jacket.

The National Rifle Association!

Cool! Ten of thirty-plus points made me a Marksman the following year, and I soon moved on to forty-plus points: a Sharpshooter. As I returned to Sunapee summer after summer, I worked my way from prone to sitting to kneeling to standing, and my skill and enthusiasm got me invited to the range at off-hours—during rest period or meals—for one-on-one instruction and the high honor of cleaning the rifles with rags, bore brushes, and banana-smelling Hoppe’s No. 9 Solvent.

It was, however, a confusingly bifurcated gun life. Aside from Hank Hilliard, I had no gun mentors. Neither my parents nor anybody in their

circle of suburban New Jersey Jewish Democrats had ever hunted or owned a gun. None, I am certain, would have dreamed of touching one. “Jews make guns and sell guns,” my mother’s friend Bubbles Binder said with a gravelly laugh. “We don’t shoot guns.” I don’t know if there were gun ranges in or near South Orange, because taking me to one would have been the last thing my gentle, mercantile father would have dreamed of doing. So while riflery was a serious sport at camp, for the other ten months of the year my gun thing was allowed to spin off into the kind of violent fantasies that, in the mid-1960s, were not considered at all odd for a little boy.

One whole aisle of E. J. Korvette’s toy department was given over to nothing but guns—Monkey Division bazookas, Johnny Seven One Man Army guns, Mattel Shootin’ Shell rifles, Hubley snub-nosed .38s, Okinawa Guns, G.I. Joes with all their lethal accoutrements, Zero-M secret-agent weapons, fabulously realistic Johnny Eagle gun sets, Fanner 50 cap pistols, Sound-O-Power M16s, Secret Sam folding-rifle spy briefcases,

Man from U.N.C.L.E

. guns, and on and on, all of them advertised relentlessly and unabashedly on

Wonderama, Sandy Becker

, and every other children’s television show. I can sing those commercials still. When I wasn’t running around the neighborhood in a plastic helmet with Chucky Blau and my Dick Tracy tommy gun, I was studying

Combat!

—“starring Vic Morrow as Sergeant Saunders”—with the devotional zeal of a Talmudic scholar. I slept with toy guns under and in my bed. I was always either holding a gun or pantomiming doing so, my hands aching for the rich fullness of stock and handgrip. Every few days, I looked up “rifle,” “pistol,” or “machine gun” in our 1960

World Book

, lingering over photos and diagrams—the intricate sweep of bolt and trigger—memorizing make, model, caliber, muzzle velocity, and cyclic rate of fire. James Bond burst into my life in 1964 like a newfound god, and I began looking forward to the rare occasions on which our parents would drag my brothers and me to Temple Israel, because services gave me an excuse to wear a suit jacket like a grown-up, which meant I could conceal a plastic shoulder holster and Luger, with a Magic Marker jammed into the muzzle as a silencer. That delicious bulk under my arm could sustain me through an entire Kol Nidre.