Gwen Verdon: A Life on Stage and Screen

Read Gwen Verdon: A Life on Stage and Screen Online

Authors: Peter Shelley

Also by PETER SHELLEY AND FROM MCFARLAND

Neil Simon on Screen: Adaptations and Original Scripts for Film and Television

(2015)

Sandy Dennis: The Life and Films

(2014)

Australian Horror Films, 1973–2010

(2012)

Jules Dassin: The Life and Films

(2011)

Frances Farmer: The Life and Films of a Troubled Star

(2011)

Grande Dame Guignol Cinema: A History of Hag Horror from

Baby Jane

to

Mother (2009)

A Life on Stage and Screen

Peter Shelley

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Acknowledgments:

Special thanks are offered to Barry Lowe and Kath Perry. Additional thanks are given to Rick McKay, Catherine Porter, Michael Schnurr, Stewart South, and Photofest.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2103-6

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

© 2015 Peter Shelley. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

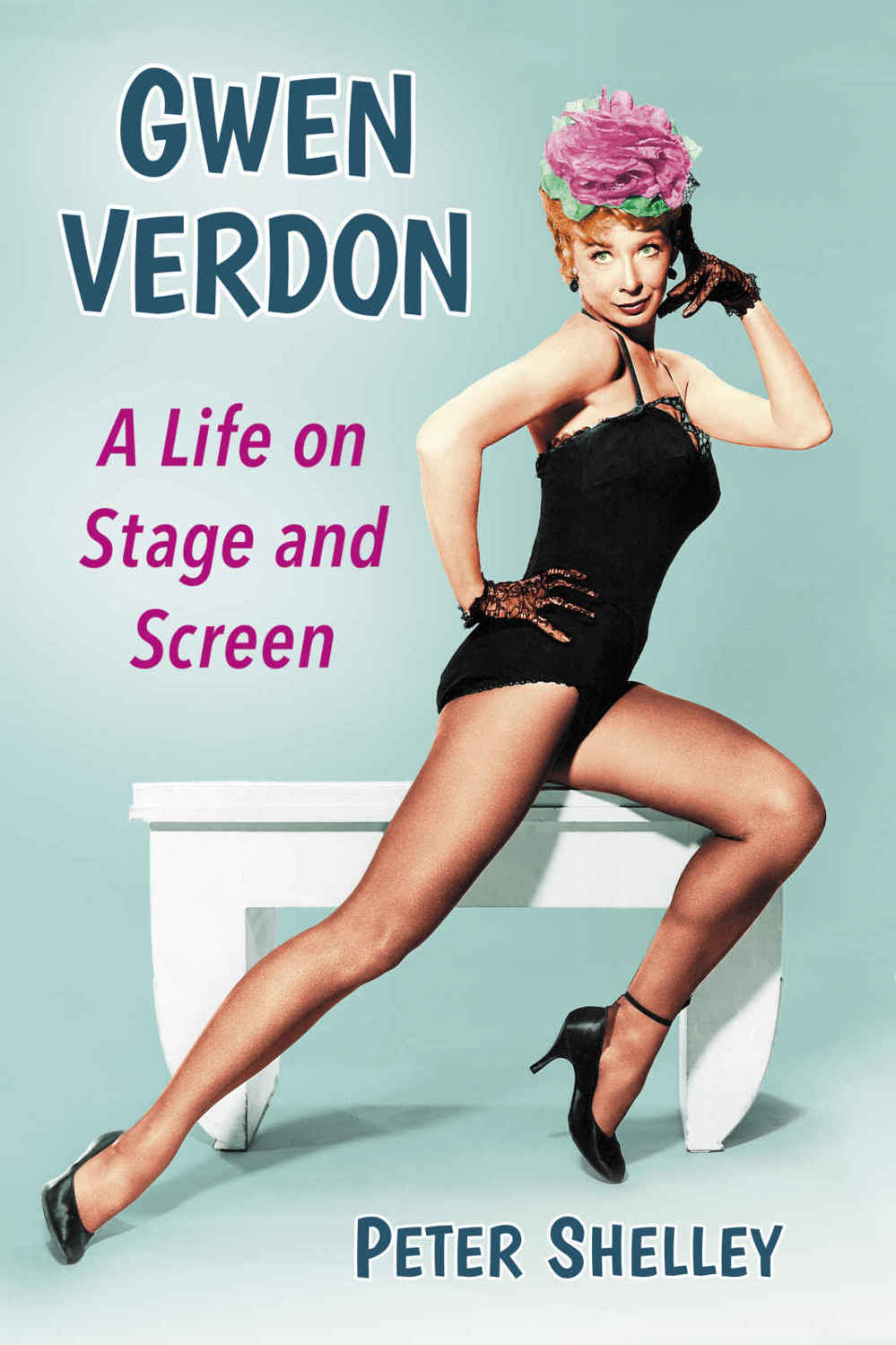

Front cover: Gwen Verdon as Lola in the 1958 film

Damn Yankees

(Warner Bros./Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

2. Working with Jack Cole in Films

4.

Damn Yankees

, Bob Fosse and

New Girl in Town

5.

Damn Yankees

on Film and

Redhead

6. Semi-Retirement and Motherhood

14. Charity One Last Time and

Fosse

Appendix: Performances on Stage, Film, Television and Record

I first became aware of Gwen Verdon in the film version of

Damn Yankees

(1958) so it was fascinating for me to discover that her association with choreographer Bob Fosse had been preceded by an earlier phase of her career. This made writing the book a journey of discovery. Verdon had a remarkable career and her life can be seen as having five separate acts, since her work in show business was interrupted by two temporary retirements. Her career can be divided into two periods when she worked with two choreographers who changed its direction. They were Fosse and Jack Cole; Verdon acted as dance assistant and muse to their choreographic ambitions. Fosse in particular was responsible for giving Verdon two of her five acts, by creating the stage show

Sweet Charity

for her and bringing her out of her second retirement.

But for someone to have had five acts in her life, she needs to be special, and Verdon certainly was that. She was an extraordinary dancer, and though her singing voice was ordinary, her dramatic abilities made up for them. Verdon’s gifts as an actor would later be displayed in dramatic roles that defined the last act of her life. In his review of her Broadway show

Redhead

, Brooks Atkinson wrote that she did everything that anyone could expect of a musical performer, and more. “She can portray character like a fully licensed dramatic actress. She can sing in a russet-colored voice that is mighty pleasant to hear … and she can dance with so much grace and gaiety that her other accomplishments seem to be frosting on the cake.”

Verdon’s persona was a combination of sexiness and innocence, qualities that have been described as Chaplinesque. She was a great admirer of Chaplin, who she called an art nouveau ballet dancer. Verdon came across as someone who was naughty but nice, a hard-luck bad girl who wore her heart on her sleeve. This paradox was embodied in her Charity Hope Valentine from the stage show

Sweet Charity

, the prostitute with a heart of gold whose need for the love of a man made her naïve and pure. More street-wise than bright, Charity was masochistic and pathetic but lovable. Verdon never got the chance to commit her stage performance to film for the ages, though we have glimpses of it in her television guest appearances. What makes some of these performances even more heartbreaking is the suspicion that she may have known at the time she did them that she was not to do the film.

There is, in fact, a sadness about Verdon’s career. Being allowed to do the film version of

Damn Yankees

after she had done the stage role did not lead her immediately to more films. She returned to the stage and would later make more films and television appearances, but the forces needed to capitalize on her triumph in

Damn Yankees

did not converge for her. This is not so unusual for performers who are mostly associated with their work in theater. Think of the limited film careers of Ethel Merman and Carol Channing. But the fact that this happened to Verdon, who already had a film career as a Jack Cole dancer, seems even more frustrating. Perhaps if Bob Fosse had decided to begin his career as film director earlier than he did, things may have been different. But this was not to be, and even when he did begin making films, he never cast Verdon.

Her golden period on stage is deemed to be a relatively brief one, from

Can-Can

in 1953 to

Redhead

in 1959. It was considered golden because Verdon enjoyed four hot shows in a row and won Tony awards for each of them, a record unequalled by any other musical actress. Her string of hits was broken after her comeback role in

Sweet Charity

in 1966. Although the show was a box office winner, it failed to earn her the Tony Award. Her disappointment must have been worsened by the fact that Fosse,

her own husband

, overlooked her for the movie version. Verdon considered that acting in musical comedies, which had been her forte, was still acting. However, her desire to do “straight” parts was not satisfied. The one attempt she made, the 1972 thriller

Children! Children!

, was a flop that closed on its opening night. Although Verdon wanted to try again, the few offers she received were badly timed, and then they dried up. Perhaps she became pigeonholed by the industry because of her own success. Even when she presented at the Tony Awards multiple times, it was nearly always for musical comedy awards. Verdon resurfaced after she decided that she was now too old to dance on stage and she transitioned to working in supporting roles in film and making television guest appearances. While it is wonderful to see her in these, there is still a sadness in the limitations of these opportunities.

This biography is the first full-length book on Verdon. She had been given a chapter in Roy Harris’ 1997 book

Eight Women of the American Stage

, but it was a small one. Verdon was also sporadically mentioned in biographies and studies of Fosse. These were Kevin Boyd Grubb’s 1989

Razzle Dazzle: The Life And Work of Bob Fosse

, Martin Gottfried’s 1990

All His Jazz: The Life And Death of Bob Fosse

, Margery Beddow’s 1996

Bob Fosse’s Broadway

, and Sam Wasson’s 2013

Fosse

. Additionally, she was featured in Glenn Loney’s 1984

Unsung Genius: The Passion of Dancer-Choreographer Jack Cole

. However, none of these books provides a satisfactory look out Verdon’s life and career as an individual. This book attempts to do so, although since some of her work for television in particular remains unavailable for viewing, it regrettably cannot be considered a definitive study.

Accessing the aforementioned sources and any associated biographies and books on Verdon’s co-workers allowed me to consider differing views of some of the events in her life and to highlight any apparent inaccuracies. My research also had me review interviews that Verdon gave to newspapers and magazines. Since not all of her work is available on DVD or video, I viewed some of her film and television guest appearances via rare collectors’ prints, and was pleased to find that some could also be seen on YouTube. Where a title could not be viewed, I have provided as much information as I could obtain. One I especially regret not being able to get was Verdon’s 1973 made-for-TV movie

Deadly Visitor

.

The book is written as a biography, with Verdon’s career presented in the context of her life. I have not made new chapters for each of the stage shows or films or television appearances or recordings. Rather they are mixed into the biography, although I have given an analysis of the work when possible. For what I have viewed and heard, I have commented specifically on Verdon’s appearance and performance, as well as provided any relevant notes on the title’s narrative. I have also discussed the critical reaction that the work received. To complement the text, I have supplied photographic portraits and stills from some of her film, television, and stage work. Additionally the book comes with a brief appendix of the star’s work and a bibliography of reference sources.

Beginning and Jack Cole

Gwyneth Evelyn Verdon was born in Culver City, at the California Lutheran Church Hospital, but the date differs according to sources. Some give it as January 13, 1925, others January 16. Her surname rhymes with “stirred-in” and not “spurred on” as

Time

magazine said in its 1955 cover story on her. Verdon said the confusion probably came from her trying to explain that the name wasn’t Vernon and then it was thought to be pronounced that way. Her name would be often spelled Vernon. People also put two ns in her first name.

She was the second child of Joseph William Verdon (December 31, 1896–June 23, 1978) and Gertrude Lillian Verdon nee Standring (October 24, 1896–October 16, 1956). The Verdons also had a son, William O’Farrell Verdon (August 1, 1923—June 10, 1991), nicknamed “Red” because of his red hair. Her parents were English immigrants who had come to America via Canada. They were show people though Joseph also worked as a gardener. Verdon’s great-grandfather was an actor in Shakespearean repertory, touring the British provinces, and her grandfather was an English step dancer. Gertrude told newspapermen that her parents were strolling players in England, which Verdon said her mother made up to deflect the press attention given to Verdon. It had the opposite effect, which led Gertrude to tell a bigger, crazier lie: that Verdon was born in the shadow of MGM studios. That too failed though Verdon herself would perpetuate the myth by using it in her own theater program biographies. She also said that she was born in between MGM and 20th Century-Fox, between the back gate of one and the front gate of the other. The family lived in a $12-a-month bungalow on Keystone Avenue near the MGM studios. The location made Verdon say that she always felt like a Keystone Cop.

Gertrude was a dancer and a veteran of Denishawn, the modern dance company founded by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. She ran a dancing school in Culver City. Joseph was also in the industry, being a second best boy electrician at MGM. It is said that he worked on nine or ten Garbo films, partially because she liked having the familiar faces of the same crew members around her. Verdon would say that when she was three, he would come home and tell her about all the big stars he had lit that day but all she ever wanted to hear about was the monkey in the Tarzan movies. Rather than ask to watch any of the MGM musical dance numbers being filmed, or Garbo, Verdon only wanted to see the Tarzans. She was intrigued with the intelligence of the monkey, and thought that he was far brighter than any human.

A series of infantile diseases afflicted Verdon at the age of two. She had measles, chicken pox, mumps, and whooping cough. She required a hernia operation and then suffered a severe case of rickets which left her in bed for months. Verdon would say that rickets was a disease of the poor and that she was born with them because of bad nutrition. Her knees were so badly knocked that they crossed over each other and gave her big sores. For a time she had to be carried from one place to another because she couldn’t walk. Also the muscles on the inside of the leg were too long for the muscles on the outside. Because of her misshapen legs, Verdon was nicknamed “Gimpy” by other children. A doctor suggested that Verdon’s legs be broken so that they could be reset and straightened but her mother disagreed. Gertrude is said to have torn up the letter with this recommendation. At first she thought of taking her daughter to an orthopedic hospital in Los Angeles, but then had a more experimental idea. Since Verdon’s problem was muscular rather than crippling, her mother insisted that that the exercise of dancing was a better therapy; a natural corrective for body defects. Gertrude is quoted as saying, “That child is like wild sunset! She

will

dance!” The dance of Ruth St. Denis had exercises that would not stretch the inside muscles because you didn’t have to turn out or use those particular muscles.