Haiku

Authors: Stephen Addiss

HAIKU

AN ANTHOLOGY OF JAPANESE POEMS

Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto,

and Akira Yamamoto

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2011

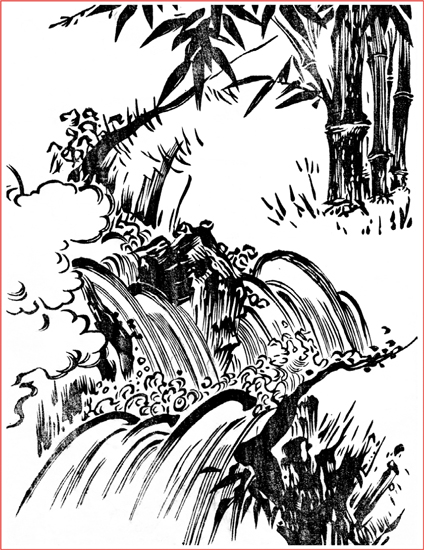

F

RONTISPIECE

:

Stream

, Tachibana Morikuni

S

HAMBHALA

P

UBLICATIONS

, I

NC

.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

© 2009 by Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Haiku: an anthology of Japanese poems / [edited by] Stephen Addiss, Fumiko Yamamoto, and Akira Yamamoto.â1st ed.

p.   cm.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2234-4

ISBN 978-1-59030-730-4 (acid-free paper)

1. HaikuâTranslations into English. I. Addiss, Stephen, 1935âII. Yamamoto, Fumiko Y. III. Yamamoto, Akira Y.

PL782.E3H236 2009

895.6â²104108âdc22

2009010381

CONTENTS

H

AIKU

are now one of the best-known and most practiced forms of poetry in the world. Simple enough to be taught to children, they can also reward a lifetime of study and pursuit. With their evocative explorations of life and nature, they can also exhibit a delightful sense of playfulness and humor.

Called

haikai

until the twentieth century, haiku are usually defined as poems of 5-7-5 syllables with seasonal references. This definition is generally true of Japanese haiku before 1900, but it is less true since then with the development of experimental free-verse haiku and those without reference to season: for example, the poems of SantÅka (1882â1940), who was well known for his terse and powerful free verse. Seasonal reference has also been less strict in

senryū

, a comic counterpart of haiku in which human affairs become the focus.

Freedom from syllabic restrictions is especially true for contemporary haiku composed in other languages. The changes are not surprising. English, for example, has a different rhythm from Japanese: English is “stress-timed” and Japanese “syllable-timed.” Thus, the same content can be said in fewer syllables in English. Take, for example, the most famous of all haiku, a verse by BashÅ (1644â94):

Furu ike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

Furu

means “old,”

ike

means “pond or ponds,” and

ya

is an exclamatory particle, something like “ah.”

Kawazu

is a “frog or frogs”;

tobikomu

, “jump in”;

mizu

, “water”;

no

, the genitive “of”; and

oto

, “sound or sounds” (Japanese does not usually distinguish singular from plural). If using the singular, a literal translation would be:

Old pondâ

a frog jumps in

the sound of water

Only the third of these lines matches the 5-7-5 formula, and the other lines would require “padding” to fit the usual definition:

[There is an] old pondâ

[suddenly] a frog jumps in

the sound of water

This kind of “padding” tends to destroy the rhythm, simplicity, and clarity of haiku, so translations of 5-7-5âsyllable Japanese poems are generally rendered with fewer syllables in English. Translators also have to choose whether to use singulars or plurals (such as

frog

or

frogs, pond

or

ponds

, and

sound

or

sounds

), while in Japanese these distinctions are nicely indeterminate.

We have attempted to offer English translation as close to the Japanese original as possible, line-by-line. Sometimes a parallel English translation succeeds in conveying the sense of the original. This haiku by Issa provides an example:

Japanese

kasumu hi no

(mist day of)

uwasa-suru yara

(gossip-do maybe)

nobe no uma

(field of horse)

Close Translation

Misty dayâ

they might be gossiping,

horses in the field

Sometimes the attempt at a parallel translation results in awkward English, and a freer translation is necessary, as with this haiku by Buson:

Japanese

yoru no ran

(night of orchid)

ka ni kakurete ya

(scent in hide wonder)

hana shiroshi

(flower be=white)

Close Translation

Evening orchidâ

is it hidden in its scent?

the white of its flower

Freer Translation

Evening orchidâ

the white of its flower

hidden in its scent

Other times a parallel translation doesn't have the impact that can be delivered in a freer translation, as in this haiku by an anonymous poet:

Japanese

mayoi-go no

(lost-child of)

ono ga taiko de

(one's=own drum with)

tazunerare

(be=searched=for)

Close Translation

The lost child

with his own drum

is searched for

Freer Translation

Searching for

the lost child

with his own drum

Thus, the challenge for translators is to try to follow the Japanese word and line order without resulting in awkward English. While admirable, sometimes adhering to the original verses may make for weaker poems in English. Sometimes the languages are too different to make a close match without hurting the flow and even the meaning. However, when closer translations succeed, they are powerfully satisfying.

The fact that the spirit of the haiku can be effectively rendered in English translation indicates that the 5-7-5 syllabic count captures the outward rhythmic form of traditional Japanese haiku but does not necessarily define them. The strength of haiku is their ability to suggest and evoke rather than merely to describe. With or without the 5-7-5 formula and seasonal references, readers are invited to place themselves in a poetic mode and to explore nature as their imaginations permit.

Returning to BashÅ's frog, what does the poem actually say? On the surface, not very muchâone or more frogs jumping into one or more ponds and making one or more sounds. Yet this poem has fascinated people for more than three hundred years, and the reason why remains something of a mystery. Is it that it combines old (the pond) and new (the jumping)? A long time span and immediacy? Sight and sound? Serenity and the surprise of breaking it? Our ability to harmonize with the nature? All of these may evoke an experience that we can share in our own imaginations.

Whatever meanings it brings forth in readers, this haiku has not only been appreciated but also variously modeled after and sometimes even parodied in Japan, the latter suggesting that readers should not take it too seriously. To give a few examples, the Chinese-style poet-painter Kameda BÅsai (1752â1826) wrote:

Old pondâ

after that time

no frog jumps in

while the Zen master Sengai Gibon (1750â1837) added new versions:

Old pondâ

something has PLOP

just jumped in

Old pondâ

BashÅ jumps in

the sound of water

BashÅ has become so famous for his haiku that this eighteenth-century

senryū

mocks the now self-conscious master himself:

Master BashÅ,

at every plop

stops walking

In the modern world, new transformations of this poem keep appearing even across the ocean, including this haiku with an environmental undertone by Stephen Addiss:

Old pond paved over

into a parking lotâ

one frog still singing

Perhaps one reason why haiku have become internationally popular in recent decades comes from our sensitivity to our surroundings, even to the development of towns and cities, often to the detriment of the natural world: poets have power to keep on singing the connection to nature in their new milieu.

Haiku in Japan

Although haiku is now a worldwide phenomenon, its roots stretch far back into Japan's history. The form itself began with poets sharing the composition of “linked verse” in the form of a series of five-line

waka

(5-7-5-7-7 syllables), a much older form of poem. W

aka

poets, working in sequence, noted that the 5-7-5âsyllable sections could often stand alone. Separate couplets of 7-7 syllables were less appealing to the Japanese taste for asymmetry, but from the 5-7-5 links, haiku were born.

It is generally considered that BashÅ was the poet who brought haiku into full flowering, deepening and enriching it and also utilizing haiku in accounts of his travels such as

Oku no hosomichi

(Narrow Road to the Interior). BashÅ's pupils then continued his tradition of infusing seemingly simple haiku with evocative undertones, while continuing a sense of play that kept haiku from becoming the least bit ponderous.

The next two of the “three great masters” were Buson (1716â83), a major painter as well as poet who developed haiku-painting (

haiga

) to its height, and Issa (1763â1827), whose profound empathy with all living beings was a major feature of his poetry. With the abrupt advent of Western civilization to Japan in the late nineteenth century, haiku seemed to be facing an uncertain future, but it was revived by Masaoka Shiki (1867â1902) and his followers, and it has continued unabated until the present day.

Despite some historical changes over the centuries, certain features of Japanese life and thought have maintained themselves as integral features of the haiku spirit. For example, the native religion of ShintÅ reveres deities in nature, both a cause and an effect of the Japanese love of trees, rocks, mountains, valleys, waterfalls, flowers, moss, animals, birds, insects, and so many more elements of the natural world. Significantly, haiku include human nature as an organic part in all of nature, as in the following poems about dragonflies by Shirao (1738â91) and the aforementioned SantÅka, respectively: