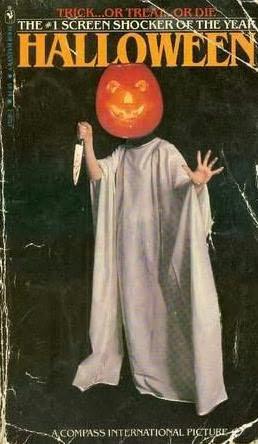

Halloween

Authors: Curtis Richards

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1979

by Bantam Books, Inc.

This book may not be reproduced In whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For informatton address:

Bantam Books, Inc.

ISBN 0-553-13226-1

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words "Bantam Books" and the portrayal of a bantam, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada.

Bantam Books, Inc.,

666 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York 10019.

The horror started on the eve of Samhain, in a foggy vale in northern Ireland at the dawn of the Celtic race. And once started, it trod the earth forevermore, wreaking its savagery suddenly, swiftly, and with incredible ferocity. Then, its lust sated, it shrank back into the mists of time for a year, a decade, a generation perhaps. But it slept only and did not die, for it could not be killed. And on the eve before Samhain it would stir, and if the lust were powerful enough, it would rise to fulfill the curse invoked so many Samhains before. Then the people would bolt their doors.

Scant good it did them, for the thing laughed at locks and bolts, and besides, there were the unwary. Always the unwary.

Samhain. The Druid festival of the dead. The summer had passed, and so too had that outburst of early fall warmth now known as Indian summer. The green had gone out of the land, the crops harvested, and the chill of winter had descended like an angel of death. The people, fearing the sun might never again warm the land, held their festival to appease Muck Olla, their deity. On hillsides and in the eaves and daub-and-wattle huts great fires were lit to which the spirits of the departed were invited by their kinsmen to warm themselves, to be cheerful before the snows blanketed the earth. Druid priests divined who would live and die in the coming year, who would marry, bear children, wax rich, enjoy good health. And they attempted to hold at bay, through sacrifices and other rites, the witches and goblins that ran amok at that time, stealing infants, destroying crops, killing farm animals . . . and sometimes worse.

Deirdre was the third and youngest daughter of the Druid king Gwynwyll. Her hair was sandy brown with amber highlights, her eyes sea green, her complexion cream and wild rose. She was already taller than her older sisters, and her early development had been the cause of much concern in-the tribal community. The other virgins tittered with envy; the married women voiced disapproval and counseled her mother to marry her off before the girl yielded to her budding impulses; the young warriors eyed her yearningly, and the old warriors thought forbidden thoughts and reflected on their faded memories.

His name was Enda. He was fifteen, and he loved Deirdre with a secret passion that tortured him and at night caused him to cry out in his sleep. When it became rumored that Deirdre's father, the king, was preparing to offer her hand in marriage, Enda consulted his kinsmen and asked if they thought his suit would be looked upon with favor. He suspected what the answer would be, but his longing overcame his embarrassment.

"Ho! Deirdre marry you?" his father cackled. "With your shriveled arm and your twitching mouth?" For Enda had presented himself wrong end first when his mother birthed him, and the midwives had made a botch of his delivery.

"She would as soon marry my goat!" howled his uncle. "Or Bulech!" his brother added, pointing to the runty dog worrying a greasy bone in the corner of their hut.

"Besides," said his father, "I'm told she's all but betrothed to Cullain."

"Now

there's

a lad worthy of that wench's pretty hole!" his uncle burst out, raising his wineskin to his fat lips, and they continued to discuss Deirdre's charms as Enda retreated miserably from the hut into the cold night.

The boy suffered tortures such as only the adolescent can. At length, he determined on a plan. If he could somehow get directly to Deirdre, he would convince her that though he was ill-favored physically, he was in every other respect a fitting candidate for her hand. This was easier said than done, however, because the virgins were closely watched by their mothers or by truculent warrior brothers. Nevertheless, one day Enda seized an opportunity when Deirdre went to fetch water from the stream at the foot of the hill. He followed her furtively, darting from tree to tree until he found her stooped over the stream, singing softly to herself as the water filled her clay pitchers.

"Deirdre?" he called timidly.

She turned and gasped, eyes round with fright.

"You! What do you want?" Her body tensed, and she seemed ready to bolt.

"I . . . I want to . . ." The panic in her face alarmed him. He had expected to startle her, but had not imagined she would greet him with such revulsion. He stepped forward, hand extended pacifically. But she jumped back, misinterpreting the gesture. She stumbled, almost falling into the stream, and Enda moved swiftly to rescue her.

"No!" she shrieked. "Get away from me, monster!" She found her feet and burst into a run, crying, "Help! Help! He means to rape me!"

Enda's body had been deformed at birth, but not until that moment had his soul been deformed . . .

And now it was Samhain, and Enda, humiliated beyond reason, stood on the perimeter of the celebrants dancing and chanting around the bonfire. In his left hand he held a fat wineskin, from which he drank often. In his right he held a footlong butcher blade which he used to cut the throats of pigs and chickens.

His eyes were fixed bitterly on the figures of Deirdre and Cullain, whirling exuberantly around the fire, to the immense approval of the tribe. For their betrothal had been announced, to the joy and relief of all.

Enda's legs shook and his body trembled in the cold night, though the heat of the fire was intense. And when the couple pirouetted past him once more, he leapt like a wildcat on his twin prey. Unarmed, their elbows linked, they didn't have a chance. Enda's blade sliced easily through Cullain's jugular and windpipe. His legs kicked out in a grotesque finale to his dance of life. Then he fell like a slaughtered bull, dragging Deirdre downward. Her head turned away, she laughed, believing that her drunken partner had merely stumbled. Enda's blade caught her with laughter on her face, the same laughter that had mocked him after she had run safely into the arms of her tribesmen the day he had approached her at the stream. The highly honed weapon plunged into her breast up to the hilt. In the clamor, no one heard the expulsion of wind from her lungs, the gurgle of blood, the whimper, or saw the look of dreadful recognition as the light faded from her eyes—except for Enda.

The thrill of revenge was the last emotion Enda knew, for a moment later he was literally torn apart by the enraged tribe. Only his head and his heart were preserved, gathered up after the frenzy had subsided, at the request of the grieving king. After Deirdre and Cullain were buried on the hallowed ground the following day, Enda's head and heart were carried to the summit of the Hill of Fiends, where cowards and other outcasts were left to rot unblessed. The king asked his shaman to pronounce a special curse over the remains of this vile murderer. "Thy soul shall roam the earth till the end of time, reliving thy foul deed and thy foul punishment, and may the god Muck Olla visit every affliction upon thy spirit forevermore."

The sky darkened and lightning flashed. The day suddenly grew black and cold, and out of nowhere gusts of snow lashed the tribal party. In the history of the tribe, it had never snowed so early in the year. Satisfied that Muck Olla had heard his prayer, the shaman summoned his people to turn their backs on Enda and return to their bereft village . . .

The celebration of Samhain's eve was transmuted over the centuries. The invading Romans carried the tradition back from the English Isles with them in the form of the Harvest Festival of Pomona, and the early Christians deemed their celebration Hallowmas. The popes of the Middle Ages consecrated November 1 as All Saints' Day, and All Hallow Even slurred into Halloween as the holiday was transmuted over the next millennium.

With the coming of modern civilization, the superstitions and traditions of the original festival lost their meaning and vitality. Token recognition could be seen in the custom of lighting candles in jack-o'-lanterns, hanging effigies of witches and goblins outside homes, and playing good-natured pranks that were a feeble cry from the mayhem of the old times. Children paraded about in costumes whose significance had long ago lost their correspondence to the terror of evil that had once gripped the world at the onset of winter. Halloween, like many of the holidays, had become an empty sham.

Except that from time to time, the innocent frolic of All Hallow Even was shattered by some brutal and inexplicable crime, and the original spirit of the celebration was brought home to a horrified world. Then the people would bolt their doors.

Scant good it did them . . . and besides, there were always the unwary.

It was 1963, and America was sure of itself, or at least seemed to be. Particularly in Haddonfield, Illinois. The tensions of the Cold War, of Cuba, the dark stirrings in Southeast Asia, lapped at the door of this placid and undistinguished midwestern town, but didn't really touch it. In less than a month, the president would be murdered in Dallas, signaling an era of tremendous violence and heartbreak that would reach deeply into the homes and hearts of Americans across the land.