Handbook on Sexual Violence (81 page)

Read Handbook on Sexual Violence Online

Authors: Jennifer Sandra.,Brown Walklate

In the initial stages of the contact, the perpetrators had first been very flattering about the girls’ photographs, and had then moved on to convincing descriptions of their experiences from the modelling industry, where they claimed for the most part to work as professional photographers. These Internet contacts continued for anything from a few days to up to two months prior to the victims meeting the men offline. With a single exception, the perpetrators had promised the victims that the modelling assignment would not involve them being photographed nude.

As a rule, the perpetrators continued in their role as photographers at least in the initial stages of the offline meetings. In a typical case, the victim would first be photographed with her clothes on, and would then be asked to undress. The perpetrator would begin to sexually assault the victim by means of unwanted sexual touching, which he might explain as being necessary to correct the girl’s poses. In the majority of cases, the sexual assault did not go any further than this sexual touching, often because the victim succeeded in getting away from the perpetrator. In two cases, however, the victims had been raped.

Offers of payment for sexual services

Nine of the police reports relating to offline offences involved men who had offered the victims money for sex. The victims in these cases comprised males and females aged between 14 and 17. The perpetrators (all male) were aged between 25 and 49. The Internet contacts between victim and perpetrator had on occasion been very short, but the majority had continued for between one month and up to three to four months prior to the offline meeting. Five of the victims had travelled to another town to meet the perpetrator, and in five cases the victim had met the perpetrator for sex on two or more occasions.

In over half of the cases, the victims had been forced to engage in sexual acts that they did not wish to perform, and which they had not agreed to in advance. It was also often the case that the victim and perpetrator had agreed prior to the meeting that the perpetrator would use a condom. In virtually all cases, however, the victims were then either persuaded or coerced into having unprotected sex with the perpetrators.

A common part of everyday life online?

Having exemplified different types of online sexual contacts, and having described a number of strategies employed to persuade potential victims to attend offline meetings, two central questions remain to be addressed. The first of these, that of the prevalence of online sexual contacts, is examined in the next

section. The second question is that of the relative frequency of different types of contacts. This is approached, a little speculatively, in the subsequent section by means of an attempt to bring the findings from the different data sets together in a simple model emphasising a number of central aspects of the online sexual solicitation phenomenon.The prevalence of online sexual contacts

The web survey questions that elicited the descriptions of online sexual contacts presented earlier first asked the youths whether they had ever had an Internet contact with a person they knew or believed to be at least five years older than themselves that they would describe as sexual. A follow-up question was then asked to elicit whether they had experienced an Internet contact of this kind before their 15th birthdays. As was noted towards the beginning of the chapter, 35 per cent of the female respondents and seven per cent of the males reported having experienced such a contact. Since we have no information about the representativeness of the web survey sample, however, we cannot use these figures as a basis for statements about the likely prevalence of contacts of this kind.

Having since had an opportunity to pose a very similar question to a representative sample of 15-year-olds at school, however, we can speak to this issue with somewhat more suitable data. At the end of 2008, 13 per cent of the school sample (21 per cent of girls and a little under six per cent of boys) stated that,

over the course of the preceding 12 months

, they had experienced an online contact that they would describe as sexual with a person they knew or believed to be at least five years older than themselves. As would be expected, experience of such contacts was much more common among those who reported that they often chatted online with people they didn’t already know offline. Among the girls who reported often chatting online with people they didn’t know, fully 45 per cent reported having experienced a sexual contact with someone at least five years older than themselves. Among the boys who often chatted with people they didn’t know, the corresponding figure was slightly over 12 per cent. The corresponding figures among the girls and boys who stated that they never or only rarely chatted online with people they didn’t know were ten per cent and just over two per cent respectively.We cannot of course be sure how many of the contacts reported in the school survey may in fact have been from other young people, rather than from adults, but there is nothing in our data to suggest that online sexual contacts from adults constitute a marginal or small-scale phenomenon. In fact several of the answers provided by youths in the online survey suggest rather the opposite, that contacts of this kind have become a more or less unremarkable part of everyday life for many young people online.

It happens almost every day that old men add you on MSN and want to start talking about sex and send on the webcam when they’re having a wank and send pictures of their sex organs.

(girl)

Everyone with different fetishes hits on you if you log in as a girl. If you log in as a boy you get loads of comments from old men. They even offer you money for sex. Try it yourself!

(boy)

Thus the data indicate that exposure to online sexual contacts of various kinds is nothing unusual for many young people today. To further contextualise the question of the significance of the Internet for the prevalence of

offline

sexual offences against children, we might also ask: What proportion of offline sexual offences against children appear to originate in Internet contacts?The fourth data set collected by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention makes it possible to provide a partial answer to this question, at least with regard to the most serious sexual offences that are brought to the attention of the criminal justice system. As was noted earlier, this data set comprises a systematic sample of 25 per cent of all sexual offences recorded by the Swedish police in 2008 under the crime codes for rape against females under the age of 18, and 50 per cent of those against males.

On the basis once again of the information contained in offence reports and interviews with the victims, it was possible to establish the nature of the relationship between perpetrator and victim in 83 per cent of the 456 cases in the sample. Of these cases, just over eight per cent involved registered suspected rape offences against young people who had first come into contact with the perpetrator online.

None of the cases identified related to victims under the age of 12. Among the female victims, online contacts accounted for a somewhat larger proportion of the recorded offences against 12–14-year-olds (15 per cent) than of those against 15–17-year-olds (8 per cent). The numbers of recorded offences against male victims are so small as to make the presentation of percentages potentially misleading (there were only 21 cases involving 12–17-year-old male victims in the entire sample). Of these, there was a single recorded suspected rape resulting from an online contact among the 12–14-year-old male victims, and a further single case among the 15–17-year-olds.

To put these figures into a broader perspective, we can note that current/ former boy/girlfriends and family members together accounted for 29 per cent (12–14-year-old victims) and 19 per cent (15–17-year-old victims) of perpetrators; and persons completely unknown to the victim, or whom the victim had met for the first time at most a few hours prior to the offence (with no prior online contact having taken place), accounted for 19 per cent (12–14- year-olds) and 35 per cent (15–17-year-olds) of perpetrators respectively. Taken together, these figures suggest that Internet contacts may well be playing a significant role in relation to the number of offline sex offences being committed, but that young people are on the whole still much more at risk from people close to them or whom they meet in the course of their social

activities in a range of offline environments.

It is also important to note that the perpetrators in a substantial minority of the cases resulting from online contacts in this fourth data set were not very much older than the victims. The perpetrator was at least five years older than the victim in approximately two-thirds of the Internet-related cases involving 12–14-year-old victims, and in just under half of the cases involving 15–17- year-old victims.

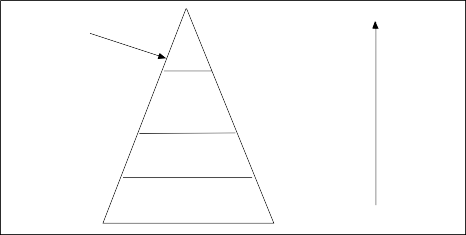

The pyramid of sexually abusive online contacts

Sexual assaults at offline meetings

More

‘Posing’ phone contacts

Vulnerability/ ‘complicity’ required from child

Amount of manipulation required from adult

Less

Adults exposing themselves

Sexual questions/ online ‘dirty talk’

Figure 16.1

The pyramid of sexually abusive online contactsAt the base of the pyramid we have a very large number of online sexual contacts that are currently being directed at young people.

Our data suggest that the majority of these contacts are probably blocked fairly quickly by the young people concerned, and are thus relatively ‘unsuccessful’ from the perspective of the would-be abuser. The question of whether contacts are likely to be successful from the abuser’s point of view would seem in part to depend on what it is that the offender wants from the young person concerned. And it would also seem to depend on whether the abuser comes into contact with a child who is in some way vulnerable to the specific approach he (or she) has chosen to use.

The prevalence of different types of Internet-related sexual offences is probably also related to the amount of manipulation required from the abuser to get the young person to do what he wants. So it’s probably

relatively

easy for an adult to manipulate children to give out their MSN addresses and then open up their webcam window so that the adult can expose himself. On the other hand, it is probably more difficult to persuade children to give out their phone numbers, to pose naked or engage in cybersex, or to agree to an offline meeting. Given the probable number of attempted online contacts, then, theproportion that result in

offline

sex offences is likely to be relatively small. At the same time, the findings from our final data set indicate that online contacts lead to a far from insignificant proportion of the more serious offline sexual offences that are coming to the attention of the police, particularly in relation to victims aged 12–14.It might be tempting to see the different levels of the pyramid in terms of a continuum through which perpetrators move in order to arrive at the ultimate goal of an offline meeting; as different ‘stages’, if you will, in a grooming process focused on creating opportunities for the

offline

sexual exploitation or abuse of children. Our data strongly suggest, however, that the reality is rather more complicated. Many online perpetrators simply do not appear to be interested in offline contacts. As is the case with offline ‘exhibitionists’ (Sugarman

et al

. 1994; Rabinowitz-Greenberg

et al

. 2002), for example, some online exhibitionists may well also be inclined towards establishing other more ‘hands-on’ forms of contact with potential victims, while others are not. Similarly, collectors of sexually exploitative or abusive images of children may or may not be intent upon having sex with children offline (e.g. Craig

et al

. 2008). Our data contained examples of adults who had first persuaded children to send sexual images of themselves, and who had then persuaded these same children to meet them offline, and both our own data, and previous research (e.g. Gallagher

et al

. 2006), contain examples of individuals having used images sent by children to attempt to blackmail these children to meet them offline. Further, the use of both (child-) pornography and ‘dirty talk’ are widely acknowledged in the research literature as means of desensitising potential victims in the context of the grooming process (e.g. Krone 2004; McAlinden 2006). At the same time, however, our own data nonetheless indicate that for many perpetrators, the sexually abusive online contact may itself be the ‘goal’ rather than a ‘means’ to some other end.More or less irrespective of the specific goal of a given perpetrator, the data sets collected by the National Council suggest a victim selection process that is as follows. The Internet provides potential sex offenders with access to a more or less unlimited number of young people. Of these young people, some are more vulnerable to contacts of this kind than others as a result of such factors as varying levels of knowledge and experience of the Internet and also a number of different background, psychological and social characteristics. The more children a perpetrator attempts to contact, the higher the probability that he will come into contact with a child who is vulnerable to precisely the type of strategy that he has chosen to use. As far as the perpetrator is concerned, we may assume that it makes little difference which of the children he contacts react positively to his approaches. Instead he exploits the fact that certain children have characteristics that will lead them to ‘self-select’ as victims. In this sense, the online sexual solicitation of children by adults is very reminiscent of other cybercrime phenomena, such as ‘phishing’, for example, or begging letters sent by email in the form of spam.