Hat Trick! (27 page)

Authors: Brett Lee

Australia: 7/324. England: 9/315.

And only four balls left.

‘She’s set herself 18 to win,’ Rahul said, smiling.

‘And just one over to get them,’ added Jimbo.

‘And with Michael Clarke bowling full tosses.’ I laughed. ‘She’s programmed him to bowl six slow full tosses at her. What a ripper!’

‘

Well, surely Australia can’t lose the World Cup from here

,’ Ian Chappell said, sounding worried. Even the crowd behind me groaned.

Georgie belted the next three balls—all full tosses—for four. Michael Clarke stood there, his hands on his hips, looking totally shattered. Everyone in the plaza was clapping Georgie as the helmet came off.

‘You guys are such nongs! Why would you want to face up to Shoaib Akhtar when you could win a World Cup against the young blond Aussie star at the home of cricket?’

We all just stared at her.

‘At least we were playing for

our

country,’ I said.

‘Yeah, well, that was one sacrifice I had to make so I could have Michael Clarke bowling at me. Neat about the full tosses, huh?’ She slapped me on the back.

BANG!

A short, sharp explosion had everyone jumping and ducking for cover. A small trail of smoke from a big black box near Alistair drifted into the air.

‘Oh, no,’ he sighed, though he was grinning. ‘I guess we’ve overworked the Blaster.’

Before we left we managed to get a card from Alistair with his phone number on it.

‘Actually,’ he said as he handed it to me, ‘I’m not really supposed to have gone public yet, but I just wanted some kids to try it out.’

‘Well, if you want a permanent volunteer for the job of testing the Master Blaster, I’m your man,’ Jimbo said.

‘Thanks,’ Alistair said. ‘I’ll remember that.’

In the first over that Ralph Phillips ever bowled in a first-class game, he took a hat trick. He was playing for Border against Eastern Province in South Africa during the 1939/1940 season.

Tuesday—afternoon

‘

I

didn’t have any luck with that Scorpions’ website,’ Georgie said, as we headed to the ovals for training.

‘Yeah? What was the site like?’

‘Pretty normal. It just had some photos, team lists, statistics and stuff like that.’

‘Anything about the Master Blaster?’ I asked.

‘Nope. Why?’

‘I dunno. I’m just suspicious about Mr Smale being at the shopping centre, talking to Alistair and speaking continuously on his mobile phone.’ I looked across the cricket ground. It was one of the few parts of the school that still had green grass; the summer had been long, hot and dry. ‘I dunno,’ I repeated. ‘He’s up to something. Plus he’s got the scorecard—there’s no way he’ll be putting that down in his precious vault.’

‘Yeah, well I gave the website address to Ally,’ Georgie said. ‘Her brother, Ben, is going to check it out and see if he can find anything.’ She picked up an old cricket ball from the long grass behind the practice wickets.

‘I looked up Master Blaster on the Net,’ I said, holding out my hand for her to throw the ball to me.

‘Anything?’ she said, tossing it.

‘Music systems, cricket bats and Viv Richards,’ I told her, catching the ball.

‘So, nothing about virtual cricket?’

‘Nup, not a sausage.’

We went for a warm-up lap of the oval, then joined the rest of the team for some stretching. I was really looking forward to this practice. Mr Pasquali always organised a special game on the second-last practice of the season. It had become a bit of a school tradition and there were plenty of school kids, parents and teachers who had come to watch.

‘Okay, people. This is the double-wicket competition,’ Mr Pasquali called, coming over to where we’d gathered. ‘You’re probably familiar with the rules but I’ll go over them quickly while you finish your stretching.’

All we really wanted to hear were the pairings Mr Pasquali had decided on, but no one spoke as he went through the rules.

‘There will be six overs per batting pair, and every pair will face six different bowlers, each bowling sixball overs. A wicket costs the batter 15 runs and also

means a change of ends for the batters. A wicket is worth 10 runs for the bowler. A run-out is worth five runs for any fielder and a catch is also worth five. I’ll organise your bowling, fielding and keeping duties so everyone gets a fair go. And there will also be bonus points.’

‘Bonus points?’ Jono asked.

‘They’ll be awarded to anyone I see doing worthwhile things on the cricket field: backing up, supportive play, a fine piece of fielding or maybe an act of sportsmanship. That’s all at my discretion.’

‘And so every run is worth…one run?’ Jay asked.

‘Exactly that, Jay,’ Mr Pasquali replied.

‘But what if my overs are against Jimbo or Jono…’

‘Jay!’ about six kids exclaimed at the same time.

‘It’s just practice. We’re a team, remember. We’ve got a big game on this Saturday,’ Mr Pasquali told him patiently.

Jay’s outburst didn’t surprise me. I guess like everyone else he wanted to perform well so he’d get picked for the grand final.

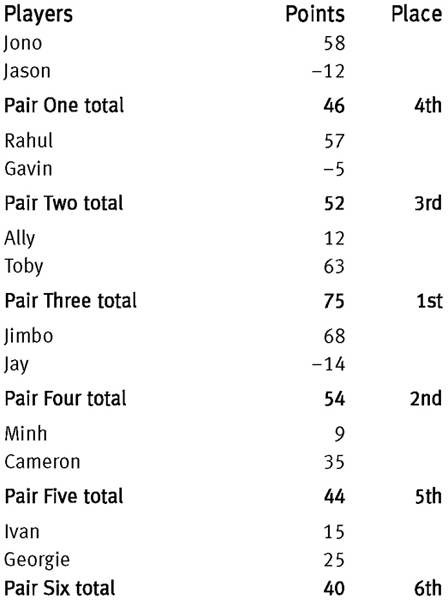

‘Righto,’ Mr Pasquali said, opening up his blue clipboard. ‘Here are the teams. Pair One: Jono and Jason; Pair Two: Rahul and Gavin; Three: Ally and Toby; Four: Jimbo and Jay; Five: Minh and Cameron; and Pair Six is Ivo and Georgie. Pair One, go and pad up. Jimbo and Jay, you’re bowling first—grab a new ball from the kit and organise your field. Cameron, you’re starting as keeper.

‘Ripper!’ Cameron said, racing over to the kit.

‘Martian looks really happy,’ Georgie muttered to me, sarcastically.

‘Well, I’m happy. And I’d be happy swapping with Martian too,’ I told her.

‘Fat chance of that,’ she said, jamming her cap down on her head. ‘And look at Ally, all excited.’

‘You and me, Tobler,’ Ally called, giving me the thumbs up.

‘See what I mean?’ Georgie said.

Jono and Jason did a great job, knocking up plenty of runs despite Jason losing a couple of wickets. It was a similar pattern with Rahul and Gavin. Rahul must have gone close to scoring 20 himself but, like Jason, I reckon Gavin would have ended up with a negative score.

Ally and I batted fourth. Our first two overs were pretty quiet, with Rahul and then Jono bowling. But no one could complain about Mr Pasquali’s organisation. The next three bowlers were not as strong and during the third, fourth and fifth overs we managed to knock up 21 runs without losing a wicket. But we were going to need a big last over to put ourselves in contention.

‘Okay, we’re right up there, Ally,’ I said, as we came together in the middle of the pitch.

‘We’ve got plenty of bowling and fielding points too,’ she added. We watched to see who would bowl our last over.

‘I reckon it’ll be Cameron,’ I said. Sure enough he walked across to the bowler’s end, passing Mr Pasquali his hat.

‘Ally, don’t do anything stupid. We lose 15 runs now and we’re sunk,’ I said, pulling my gloves back on.

Ally blocked the first two balls and we scampered through for a single from the third. Cameron’s next ball was a slower delivery outside off-stump and I swished at it. The ball clipped the outside edge of the bat and flew away over point. Jason hurled himself into the air but the ball just grazed his fingertips before racing away to the boundary for four.

‘You were saying?’ Ally smirked as we met midpitch.

‘It was there to be hit,’ I said. She rolled her eyes.

We scored another three runs off the last two balls, but only Mr Pasquali knew what the exact scores were as Pair Five went to put batting pads on.

By 10 to six everyone had batted, bowled, kept wicket and fielded in just about every position on the field. We collected the gear and pulled bottles of soft drink from Mr Pasquali’s big blue Esky as we waited for him to add up the final scores.

‘Right!’ he said, looking up from his clipboard. Jay passed him a bottle of iced water.

‘Do I get a bonus point for that?’ he asked, grinning.

‘Why not?’ Mr Pasquali said, making a little note on his clipboard. I looked over at Jimbo. He shook his head slightly and smiled. We both knew Jay wouldn’t get a bonus point for that.

Mr Pasquali took a long drink from the bottle, slowly screwed the lid back on and put the bottle down

on the grass. The spectators moved in closer, while we sat down and waited for Mr Pasquali to speak.

‘That was perhaps the best double-wicket competition I’ve seen at this school in all my years here,’ he began, looking around at each of us. ‘And it demonstrated well the importance of protecting your wicket when batting—only one pair survived their six overs without losing a wicket.

I looked over at Ally, who beamed at me. Georgie was picking grass angrily. Mr Pasquali held up his clipboard, and we all crowded around to see the results.

‘Tobler, we would have won even if we’d lost a wicket,’ Ally said, as we looked at the final totals.

‘You can see all the batting, bowling, catching and bonus point scores on the sports notice board tomorrow,’ Mr Pasquali said, tucking the clipboard under his arm. ‘And I shall see you here at four o’clock on Thursday, warmed up and ready to go.’

‘Will we be in the nets or out on the centre-wicket?’ Jono asked.

‘Nets,’ Mr Pasquali replied. ‘I’ve got a little treat for you.’ He smiled, waved goodbye and headed over to the kit.

‘Wow, I wonder what he’s got in mind?’ I said to Jimbo.

‘I think I know,’ he muttered.

‘And that would be?’ Rahul asked.

But I didn’t hear Jimbo’s answer. Ally was motioning me over to her dad’s car.

‘Tobler, Georgie told me about that card.’

I looked at her blankly.

‘You know, the business card? The one you guys saw when you ran into Mr Smale at the Scorpions’ rooms? Look!’ Ally handed me her mobile phone. ‘Read the text message,’ she said excitedly.

I read it softly to myself.

hey ally, u were right, website weird, bring yr friends over – esp Georgie – got s’ing to show u, B

‘Especially Georgie?’ I said, looking at Ally.

‘I know, weird, huh?’

‘What, the Georgie bit or the website thing?’ I asked.

‘Nah, the website. Ben’s always had a soft spot for Georgie,’ she laughed.

‘Yeah? How old is he?’

‘Fifteen, going on 11,’ Ally said. ‘So, do you want to come around and have a look tomorrow night? Georgie’s calling round after tea.’

‘You bet,’ I said, trying not to sound too eager. But before that I wanted to go and have one more look at the Scorpions’ oval and clubrooms. Especially the clubrooms.

Richie Benaud—who was the Australian captain in the 1960 Tied Test—achieved the bowling figures of 3.4 overs, 3 maidens and 3 wickets for 0 runs in a Test match against India in Delhi during the 1959/1960 season.

Wednesday—afternoon

I

left the bike at home, opting for my skateboard, which I hadn’t ridden for weeks. I stuck to the pavement, enjoying the sound and rhythm of the board as it sped over the cracks in the concrete.

There was only one stretch where I had to pick it up: the dirt and gravel road that was the entrance to the Scorpions’ ground. I thought of taking the path that wound its way through the cemetery that was next to the oval but I didn’t want to be here for too long.

There was no one about apart from a guy jogging with his dog on the far side of the ground and an old couple heading into the cemetery with some flowers.

I walked over to the clubrooms, leaned my skateboard against the wall but decided to keep my helmet on. I placed my palms against a window and pushed to the right. Luckily it opened. Taking one last glance around, I moved the curtain aside and quickly climbed through the opening. I found myself in the

main room, which I recognised from when Georgie and I had snuck in here a few weeks ago, trying to find out more about Smale.

I’d only just slid the window closed when I heard a truck approaching. I crouched below the sill, thinking that it was probably another visitor to the cemetery—maybe the gardeners. I craned my head up to look through the window and saw the truck edge past the cemetery entrance, coming towards the clubrooms. I heard it come to a stop around the corner of the building, out of sight.

I ducked away from the window and tried the door to Smale’s office. Predictably it was locked and so too was another door nearby. I was just heading over to a notice board where a huge Master Blaster poster was pinned when I heard keys jangling over by the main door.

I darted back to the window, wrenched it open and jumped out, half expecting a voice to shout at me as I scrambled over the edge.

I stood still outside the open window, my back stiff against the warm bricks of the building. My heart was thumping as the main door creaked open. I carefully pulled the curtain aside a few centimetres and peered through the gap.

Phillip Smale was entering the room backwards, pulling a trolley with three silver boxes piled up on it. He struggled with their weight as he unloaded them. A few moments later Alistair followed him in, carrying a large cardboard box.

‘It’s good of you to look after the Blaster, Phillip,’ Alistair said, putting the box down.

‘It’s an absolute pleasure, Alistair,’ Smale said. They both headed out and I waited a few minutes, concealed as I was from the truck and the main entrance. The two of them soon returned, this time Alistair with the trolley in tow.

‘Now I have something to show

you

,’ Smale said as they began stacking up the boxes.

‘Oh, actually—’

‘No, no,’ Smale interrupted him. ‘You have no choice, Alistair. You’ve shown me the Master Blaster. I’ve got something even more impressive.’

‘Well, thanks, Phillip, but—’

‘There,’ Smale continued, totally ignoring Alistair. ‘It’s all completely safe here, I assure you. Now come along. You were telling me about that one-day game you went to in Sydney, when Michael Bevan hit the winning runs?’ Smale’s voice trailed off as the two left the building again.

The truck’s engine started up. What was Smale up to? I wondered. Was Alistair in trouble? I stayed hidden as the truck slowly headed back out of the grounds. It stopped at the exit, waiting for some traffic to pass.

I tucked the skateboard under my arm and sprinted down the driveway. The truck pulled out, turning left onto the street. It accelerated away, but almost immediately slowed down again. I dropped my skateboard, wheels down, and jumped on, pushing quickly with my right foot.

In no time I had caught up to the truck. Careful to stay on the left (and hopefully out of sight of Smale’s outside mirror), I edged up alongside it. A bank of cars, all with their headlights on, was coming down the other side of the road; it was a funeral procession. The truck came to a halt—maybe Smale wanted to turn right? But there was no way he was going to get across unless someone let him through.

I jumped when Smale honked his horn, obviously impatient to get moving. The truck jerked forwards then stopped. There was a screech of brakes, another horn blast and the sound of crunching metal and shattering glass.

The truck moved forwards again, and I grabbed onto a thin pipe at the back. Suddenly I was being towed along, the skateboard wheels crunching and grinding through the broken plastic and pieces of glass that were spread all over the road.

I stole a glance at the angry and surprised faces of the people in the damaged car then concentrated on staying on my board as the truck swung right into Hope Street.

We quickly left the blaring horns behind us and raced up the street. For a moment everything was going smoothly and I had time to wonder what on earth I was going to achieve by hanging onto the back of a truck.

Then it hit a road hump and my hands flew off the pole. I threw my arms out to balance myself, crouched low and sailed off the top of the bump.

But Smale had stopped the truck. I ducked, instinctively throwing my arm out to protect my face as I smashed into the back of it. My shoulder took the force of the collision, the skateboard skidding out from underneath me and flying beneath the truck.

I lay on the road, slightly dazed, then picked myself up and ran around to the passenger side. Jumping onto the step, I opened the door. To my amazement, the cabin was empty.

Readjusting the straps of my helmet, I clambered in, desperately searching for something: a

Wisden

, the scorecard, anything to give me a clue as to what had just happened. But there was nothing but food wrappers and empty drink cartons.

I climbed back down, looking left and right. The line-up of funeral cars was still visible at the bottom of the street, crawling towards the cemetery, but Hope Street was deserted.

I dived beneath the truck and kicked my board back towards the gutter.

‘When will you bloody learn?’ Smale snarled, suddenly appearing as I picked myself up.

‘Where’s Alistair?’ I asked.

‘

Where’s Alistair?

’ he mimicked. ‘Look, this is not some Famous Five adventure, you interfering little creep. Now get into the truck.’ He stood over me threateningly, quickly glancing up the street.

‘Where’s Alistair?’ I repeated.

‘Oh, for God’s sake, he lives here.’

As Smale spoke, I glanced down at my skateboard, but he must have noticed my look and thrust his leg out just as I jammed my own foot onto the end of the board to flick it up. We both kicked it at the same time, and it shot forwards, straight into Smale’s shins.

As I stooped down to pick it up Smale grabbed me by the collar, swore viciously and dragged me smartly to the back of the truck. His grip was vice-like. He pushed me up the steps and I was hurled into darkness as the doors slammed behind me.

I yelled and thumped on the metal, praying someone would hear. But the street had been deserted and a moment later I heard the driver’s door close.

‘Alistair!’ I yelled, hoping like hell that he’d noticed something from his house. But the truck lurched forwards and I was flung into the side, banging my head against some wooden boards.

I stumbled to my feet and bashed away at the lock, even using my skateboard as a hammer, but the doors didn’t budge. There was no way I could open them; I’d heard Smale slide bolts across on the other side after he’d tossed me inside.

A wave of panic flooded through me as I realised the situation I was in: trapped in a truck, going to some unknown destination and, worst of all, no one knowing I was here—except the weird, crazy man who was driving. Smale was probably taking me out to the edge of town, away from people. What was his plan?

The truck came to a halt; maybe we were at some traffic lights? Suddenly someone was working on the lock, and I threw myself to the back of the truck. The enclosure filled with light as the doors swung open.

‘Well, Toby Jones, I always like to give someone a sporting chance. Get out!’

We had pulled over at the top of a hill, on the steep road that ran past the old cement works. A thin path snaked its way down the left side of the road, while to the right there was a steep drop. Scrubby bushes, dirt tracks, rubbish, old fence wire and discarded signs lay scattered about, all covered with white cement dust.

I swallowed. My throat had gone dry.

‘Oh dear, what a silly thing for you to do,’ Smale chuckled. ‘And in the week of the grand final too.’

‘You can’t make me go down there,’ I said, looking over the edge of the path. The first 20 metres were very steep before it levelled out slightly. I glanced around, preparing to make a dash for it.

‘And you can think again about running away. I’ll find you—you and the old man. I can make your life a misery, and I will.’

‘We just want the scorecard back,’ I said.

‘Oh, save me. Take the drop, Toby Jones, or I will haul you off to the police.’

‘What for?’ I yelled, turning on him. ‘I’ll just tell them that you kidnapped me!’

‘How about breaking into the Scorpions’ clubrooms, for one?’ he sneered. ‘Now hop on your

silly skateboard and get out of my sight.’ A cool wind blew across the top of the hill.

‘I’m going to sit down,’ I mumbled, walking to the edge.

‘Sit down, stand up—do I really care?’

I took one last look around, then slowly sat down on the board, gripping either side and rocking gently to get evenly balanced.

Suddenly Smale’s foot slammed into my back. I swore loudly as I wobbled to the left, then over the top of the rise. I jerked back to the right to regain my balance as the board plunged over the precipice.

Smale’s laughter faded quickly as I tore down the first section of concrete path. For a split second I thought of purposefully falling off; what were a few scratches, or maybe a sprained wrist or ankle? But within seconds my speed was so great that I knew I’d be hurt badly.

Oh, God!

I was frozen in terror as I hurtled down the steepest hill in town. The whistling of the wind and the screeching roar of the wheels being torn and shredded by the rough path drowned out all other sounds. There was no rhythm in the cracks in the pavement—there was just one crazy, frightening blur of noise as the wheels tore over the path at a million miles an hour. I held on in desperation, my fingers stiff from the tension of gripping the edges of the board so tightly. I had it balanced, but one slight stumble, one little wobble, and I’d be crashing at 40 kilometres per hour.

I screamed as I picked up even more speed on a short drop that was almost vertical. Somehow I managed to keep all four wheels on the path. There was nothing for it but to hold on—and pray.

Just when I thought the hill was never going to end, the track started to level out, weaving to the right. I leaned into the curve and the board responded, taking the bend at a frightening speed. I leaned back suddenly to the left to avoid a small rock that was sitting in the middle of the path. The board wobbled right, then left. For an awful moment I thought I was finally going over. I closed my eyes, my last thought being a desperate prayer for no major injury that would cause me to miss the grand final.

The board ran straight over an empty bottle which exploded into hundreds of shards. Some of the pieces must have jammed in the wheels, which sent out tiny splinters of glass.

By now I was totally out of sight of the top of the hill, and I was finally slowing down. I swung back onto the middle of the path and rode along for several more metres before steering the board off to the right.

Straight away I heard it—Smale was driving the truck slowly down the hill, no doubt to see what had happened.

I kicked the skateboard off to the other side of the track, and threw myself down into the dirt, lying spread-eagled. I held my breath and waited.

Pressing my face into the dust, I heard the truck

idle past, slowly, before disappearing down the street. I stayed where I was for another few moments then carefully staggered up, grabbed my board and started the tough walk back up the hill. It was long and steep but still the shortest way home.

That could have been a whole lot worse, I thought to myself as I turned at the top of the hill and looked back at the slope I’d just ridden.

‘Is that you, Toby?’ Mum called when I finally got home.

‘Yep,’ I answered, heading for the bathroom. I washed away the blood and grime, then gave Georgie a ring. I had to tell someone about my skateboard ride, and better her than Mum.