Have His Carcase (52 page)

Authors: Dorothy L. Sayers

want to forget.’

‘Can’t be that. For one thing, he’d have had it handy, in an outer pocket –

not tucked away in a case. And besides—’

‘Not necessarily. He’d keep it handy til he got to the place and then he’d

tuck it away safely. After al, he sat at the Flat-Iron alone for an hour or so,

didn’t he?’

‘Yes, but I was going to say something else. If he wanted to keep on

referring to the letter, he’d take – not the cipher, which would be troublesome

to read, but the de-coded copy.’

‘Of course – but – don’t you see, that solves the whole thing! He did take

the copy, and the vilain said: “Have you brought the letter?” And Alexis,

without thinking, handed him the copy, and the vilain took that and destroyed

that, forgetting that the original might be on the body too.’

‘You’re right,’ said Wimsey, ‘you’re dead right. That’s exactly what must

have happened. Wel, that’s that, but it doesn’t get us very much farther. Stil,

we’ve got some idea of what must have been in the letter, and that wil be a

great help with the de-coding. We’ve also got the idea that the vilain may have

been a bit of an amateur, and that is borne out by the letter itself.’

‘How?’

‘Wel, there are two lines here at the top, of six letters apiece. Nobody but

an amateur would present us with six isolated letters, let alone two sets of six.

He’d run the whole show together. There are just about two things these words

might be. One: they might be a key to the cipher – a letter-substitution key, but

they’re not, because I’ve tried them, and anyway, nobody would be quite fool

enough to send keyword and cipher together on the same sheet of paper. They

might, of course, be a key-word or words for the

next

letter, but I don’t think

so. Six letters is very short for the type of code I have in mind, and words of

twelve letters with no repeating letter are very rare in any language.’

‘Wouldn’t any word do, if you left out the repeated letters?’

‘It would; but judging by Alexis’ careful marking of his dictionary, that simple

fact does not seem to have occurred to these amateurs. Wel, then, if these

words are not keys to a cipher, I suggest that they represent an address, or,

more probably, an address and date. They’re in the right place for it. I don’t

mean a whole address, of course – just the name of a town – say Berlin or

London – and the date below it.’

‘That’s possible.’

‘We can but try. Now we don’t know much about the town, except that the

letters are said to have come from Czechoslovakia. But we might get the date.’

‘How would that be written?’

‘Let’s see. The letters may just represent the figures of the day, month and

year. That means that one of them is an arbitrary fil-up letter, because you

can’t have an odd number of letters, and a double figure for the number of the

months is quite impossible, since the letter arrived here on June 17th. I don’t

quite know how long the post takes from places in Central Europe, but surely

not more than three or four days at the very outside. That means it must have

been posted after the 10th of June. If the letters do not stand for numbers, then

I suggest that RBEXMG stands either for somethingteen June or June

somethingteen. Now, to represent figures our code-merchant may have taken 1

= A, 2 = B, 3 = C, and so on, or he may have taken 1 as the first letter of the

code-word and so on. The first would be more sensible, because it wouldn’t

give the code away.* So we’l suppose that 1 = A, so that he originaly wrote

A? JUNE or JUNE A? and then coded the letters in the ordinary way, the ?

standing for the unknown figure, which must be less than 5. Very good. Now, is

he more likely to have written June somethingteen or somethingteen June?’

* The hypothesis that RBEXMG represented a date written entirely in numerals proved to

be untenable, and for bravity’s sake, the calculations relating to this supposition are

omitted.

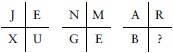

If you’re coding the pair of letters DE, then, by taking the letters to the right of

them (by the horizontal rule) you get DE = ER; the letter E appears both in

code and clear. And the same for letters that

immediately

folow one another

in a vertical line. Now, in our first pair EX = JU, this doesn’t happen, so we

may provisionaly write them down in diagonal form

‘Most English people

write

the day first and the month second. Business

people at any rate, though old-fashioned ladies stil stick to putting the month

first.’

‘Al right. We’l try somethingteen June first and say that RBEXMG stands

for A? June. Very good. Now we’l see what we can make of that. Let’s write

it out in pairs. We’l leave out RB for the moment and start with

EX

. Now EX

= JU. Now there’s one point about this code that is rather helpful in decoding.

Supposing two letters come next door to one another in the code-diagram,

either horizontaly or verticaly, you’l find that the code pair and the clear pair

have a letter in common. You don’t get that? Wel, look! Take our old key-

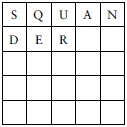

word SQUANDER, written in the diagram like this:

Taking these letters as forming the corners of a paralelogram, we can tel

ourselves that JX must come on the same line in the diagram either verticaly or

horizontaly; the same with JE, the same with EU, and the same with UX.’

‘But suppose JN folows the horizontal rule or the vertical rule without the

two letters actualy coming together?’

‘It doesn’t matter; it would only mean then that

all four of them

come on

the same line, like this: ? J E U X, or X U E? J or some arrangement of that

kind, So, taking al the letters we have got and writing them in diagonals we get

this:

Unfortunately there are no side-by-side letters at al. It would be very helpful if

there were, but we can’t have everything.

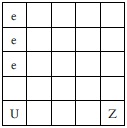

‘Now the first striking thing is this: that U and X have to come on the same

line. That very strongly suggests that they both come in the bottom line. There

are five letters that folow U in the alphabet, and only four spaces in which to

put them. One of them, therefore, must be in the key-word. We’l take a risk

with it and assume that it isn’t Z. If it is, we’l have to start al over again, but

one must make a start somewhere. We’l risk Z. That gives us three possibilities

for our last line: UVXYZ with W in the key-word, or UWXYZ with V in the

key-word, or UVWXZ with Y in the key-word. But in any case, U must be in

the bottom left-hand corner. Now, looking again at our diagonals, we find that

E and U must come in the same line. We can’t suppose that E comes

immediately above U, because it would be a frightful great key-word that only

left us with four spaces between E and U, so we must put E in one of the top

three spaces of the left-hand column, like this:

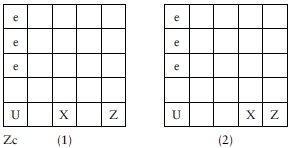

‘That’s not much, but it’s a beginning. Now let’s tackle X. There’s one

square in which we know it

can’t

be. It can’t come next to U, or there would

be two spaces between X and Z with only one letter to fil them; so X must

come in either the third or the fourth square of the bottom line. So now we have

two possible diagrams.

‘Looking at our diagonal pairs again, we find that J and X come in the same

line and so do J and E. That means that J can’t come immediately above X, so

we wil again enter it on both our diagrams in the top three squares in the X line.

Now we come to an interesting point. M and N have got to come in the same

line. In Diagram 1 it looks fearfuly tempting to put them into the two empty

spaces on the right of J, leaving K and L for the key-word; but you can’t do

that in Diagram 2, because there’s not room in the line. If Diagram 1 is the right

one, then M or N or both of them must come in the key-word. M and E come

in the same line, but N can’t come next-door to E. That warns us against a few

arrangements, but stil leaves a devil of a lot of scope. Our key-word can’t

begin with EN, that’s a certainty. But now, wait! If E is rightly placed in the

third square down, then N can’t come at the right-hand extremity of the same

line, for that would bring it next to E by the horizontal rule; so in Diagram 1 that

washes out the possibility of JMN or JLN for that line. It would give us JLM,

which is impossible unless N is in the key-word, because N can’t come next to

E and yet must be in the same line with it and also with M.’