Hawthorne: Tales of a Weirder West (9 page)

This time his aim was truer—the arrow hit home in the face of its target, and one more demon dropped.

The last three did not react, only crept forward with chilling single-mindedness, relentlessly, inevitably. Hawthorne prepared another arrow just as they gained the bottom of the ridge and started to climb up. The green glimmer of their spiders shot to and fro with maniacal energy.

Gritting his teeth, Hawthorne aimed at the top of the nearest shaggy head and released the bowstring. He was close enough to hear the thing's creaking moan as it fell back, dead, to the dirt below.

He took another arrow from Anpao. Only one more remained in her hand.

One of the two remaining creatures cleared the top of the ridge, pulling its lanky white body over the edge, staring blankly. It reached out one cadaverous hand and gripped the leg of Hawthorne's trousers.

Hawthorne jerked away, kicked the creature in the face, and swung the bow around to aim. He released the arrow point-blank, and it thudded so solidly into the thing's face that the tip peeked out from the back of its skull. It slumped backward and tumbled down the rocky incline, its spiders dissipating like fog.

Anpao shoved the last arrow into his hand and he nocked it, pulled back the bowstring to slay the final creature. He took a step toward the edge, peered down, all his senses keen for the kill now.

The last

Iktomi

was nowhere to be seen.

His eyes skipped over the bottom of the ridge. Nothing, only the still forms of the dead, sprawled out in the dirt. He stepped quickly to the other end, looked down the steep incline, saw nothing.

"Where—" he said, and Anpao screamed.

The last

Iktomi

dropped down from an overhanging tree in front of him, knocking the bow from his hands. It wrapped its fingers around Hawthorne's throat in a vise-like grip.

No spiders this time, no shimmering monsters taking solid form to seed him, only the iron grip of the demon's hands, choking out his life. It lifted him off the ground by the neck, squeezing, and Hawthorne flailed and kicked his legs. He pried at the strong fingers, punched and kicked, but the creature's grip only tightened.

Black eyes burned with glee. White hands throttled him, and Hawthorne knew he was going to die. His long journey would end here, in the middle of a dark forest in the Black Hills of South Dakota, and his bloody purpose in life would be forfeit.

Hawthorne heard a sound through the pounding of blood in his head, a soft

thwip

—and the demon's face went blank.

The grip around his throat slackened and he fell to his knees. The

Iktomi

, an arrow jutting from its neck, tottered on its feet. The black eyes focused briefly on him, and then it toppled over the side of the ridge.

The girl still held the bow in shooting position, and her face was white with fear. Hawthorne stood up, rubbing his throat. As he watched, Anpao lowered the bow, took a deep breath. Tremors began to rack her body and she dropped the weapon and looked at him.

Drops of fresh rain spattered down on their heads from out of the dark sky, sporadically at first, and then with force, and they only stood there on the ridge until they were soaked to the bone.

After a time, Hawthorne said, "Maybe I'm not the only one for the job after all."

She shook her head. "No. If I had it, if I had that hate, it's gone now. It died. It died with the last of those demons."

He glanced down at the bodies of the Spider Tribe, littering the base of the ridge, and gazed again at the girl. He said nothing.

The rain turned silver in the moonlight and Hawthorne turned his face away from it.

Part One

-

The Scarred Man

Charlie Peeples never slept well, even though he had the old station house to himself. He lay there on his rickety wooden cot and stared at the cracks in the ceiling and the cobwebs in the corners and felt anxiety in his bones. He felt the fear that the Sisters would call upon him in the night and kill him.

He would imagine them in their lair, directly below him, in the dank dirt cellar. Did the Sisters even sleep? Eyes wide open and staring, Charlie Peeples could see them in his mind's eye, standing close together and hissing unholy secrets to each other in the dark.

So he would sleep in troubled fragments, waking with every creak of wood or howl of wind or rowdy caterwauling from one of the fort's newer residents.

Funny thing was, Charlie was probably the only man in the fort relatively safe from the Sisters. He was the one they called upon when they needed fresh blood. And Charlie provided it.

That night, as he lay there not sleeping, they summoned him once again.

It started, like always, as a dull hum at the back of his skull, as if a distant train was rumbling in on the long-disused tracks that ran by the station house. The humming grew until his brain rattled and he gritted his teeth and pushed palms against his temples.

And then the dual sing-songy voices, lilting and sinister in their seeming innocence—

Charlie. Charlie Peeples ... You must come to us, Charlie ...

He rose from his cot, trembling, as the voices trailed off into little girl laughter. He stumbled in the dark until he found the lantern, lit it, and made his way to the trapdoor behind the dusty ticket counter.

Come, Charlie

, the voices buzzed.

He stared at the trapdoor for a long moment, dreading it as always, until the Sisters sent a jagged current of pain through his skull and he winced and scrambled to open it.

The smell of them came rolling out, through the close quarters of the station house. They stank of rotten meat and death. Charlie knew he'd inherited that from them, that stench. They took and took, and gave only that in return.

He raised the lantern and descended into the dark.

The Sisters lived in blackness. The cellar amount-ed to nothing more than a small, wet hole in the ground, but it was their home. It was where Charlie had first found them, where they had always lived, as far as he knew.

He negotiated the treacherous wooden steps, breathed in the stink. The numerous wounds on his chest from the Sisters' attentions ached dully.

Charlie

, they said, from somewhere in the darkness.

Come closer.

The lantern light bathed the cellar in pale yellow blotches. Charlie peered through it. Near the far wall, he spotted their small, slender forms.

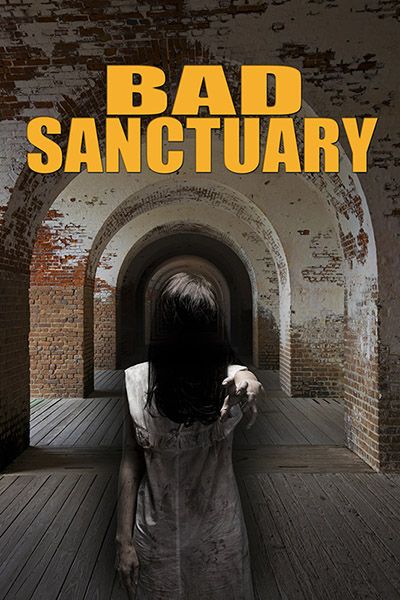

To an outsider, and in the dim, uncertain light, they would have been mistaken for two little girls, about ten years old, wearing torn and dirty dresses and holding hands. Dark tangled hair hung over their faces, obscuring their features. Charlie was thankful for that.

"I'm here," he said, his voice shaking and weak. "Do you ... do you need to feed?"

Soon enough

, the Sisters said.

We will have our fill. But now, Charlie, there is something more pressing.

Their voices cut through his skull and pounded in his brain. They had never spoken to him with actual words. He doubted they could.

He said, "What ... what is it?"

A man comes. He is the Son. We must have him.

Charlie frowned. "I don't understand that. I don't know what you're talking about. You're gonna have to use plain words."

We sense him coming. He comes for us. He is the Fallen Son, Charlie. He is the Scarred Man. He will come with the sunrise.

Charlie shook his head, confused. "Scarred Man," he said.

You will know him by his mark, Charlie. He would kill us, but for you. You will bring him before us.

"I don't rightly know what you mean. Some fella coming here? Someone you want me to bushwhack or something?"

When midnight comes. When midnight comes it will be time for Plague. Fun, fun Plague. And the Fallen Son will be our feast. You will bring him.

Charlie said, "Well ... I'll ... I'll do what I can, I reckon, but I don't rightly understand."

The Sisters giggled in the dark, holding hands, shaggy heads pressed together. They didn't move.

Charlie said, "Anything ... anything else, then?"

Yes. Feed. We believe we will feed after all. Something to whet the appetite.

"You mean ..."

The Sisters looked up at him and their hair parted and he could see their horrible, inhuman faces.

Come closer, Charlie. Give us a taste of your blood.

"No," Charlie said. "Please."

Just a taste, Charlie. Now.

He set the lantern on the ground, fought back the revulsion, and unbuttoned his shirt.

* * *

Hawthorne trotted the Morgan out of the shadowed woods and dismounted outside the main gate of the fort. The sun was just straining up against a pallid morning sky, scattering mist along the low ground and the gnarled roots of the pine trees. There was a crisp chill in the air, and fog snaked down and around the low hills.

There was a fifty-pound sack of salt loaded behind the saddle. He heaved it up, tore it open, and began spreading it.

Ten minutes later, the sack was empty. He tossed it aside, hitched the horse to a tree a few yards away, and entered the dilapidated remains of Fort Mason.

He walked through the wide-open doors, into the dirt square, his sharp gray eyes alert and cautious. There were a lot of tents and make-shift shacks and even more empty spaces. The place smelled of corruption and unwashed flesh. And there was something else—an uneasy atmosphere, a vague aura of dread that hung over the fort like a looming storm.

The Army had abandoned the fort after the plague the previous year, and the hostile Utes they'd been there to fight hadn't come within ten miles of the place since.

The Utes knew the place was bad.

But a few outlaws, stragglers and hangers-on didn't have the sense the Indians had, and now called it home. In the windows and doorways of some of the former barracks and officer's quarters, Hawthorne caught glimpses of movement.

A small train station built of splintered pine and rough stones butted up against the train tracks at the far end of the fort. Weeds were snagged in the rails. Most of the loading platform had been dismantled for spare lumber. On the other side of the tracks, a rusty water tower trickled brown water into the dirt.

Hawthorne walked into the station.

A tall, gangly, sick-looking man stood at the counter, his hands resting in front of him like two big, pale fish. He appeared to have been doing nothing but standing there before Hawthorne came in. He stank of rot.

"Good morning to you, sir. If you're waitin' for the train, I'm afraid you got a long haul ahead of ya. It don't stop here no more."

Hawthorne ignored the death smell on the man, said, "Are you the station master?"

"Was. Once upon a time. Now, well ... I'm just a fella that lives here."

Hawthorne noticed the cot in the corner of the room. He reached into his coat and pulled out a crumpled wanted poster. He put it on the counter, said, "I'm looking for this man."

The former station master frowned, looked at the poster without touching it.

"Can't say ..." the station master cleared his throat. "Can't say as he looks familiar, mister. Why you looking for him, you don't mind me asking?"

Hawthorne said nothing, and finally the station master cleared his throat again and tried, "Are you, uh, the law? Or a bounty hunter?"

Hawthorne leaned in close and spoke in a low voice, full of constrained violence. "This man left the nearest town a week ago, riding out in this direction. He's been through here. So are you gonna make me ask you again?"

The station master blanched, stuttered, "Well, I ... that is to say, I might could have seen a man riding through. Fact is ... fact is, sir, he might well could still be around here. Somewheres."

"Where? The barracks?"

"No, sir. There's a stone building not ten paces from this station, sir. The Army used to use it as a brig. Could be you might find something, well, helpful there."

Hawthorne shoved the poster back in his pocket and walked away.

Just as the station master had said, the stone building squatted forlornly next to the station. It was the only structure Hawthorne had seen in the fort not made of wood, and not looking flimsy as a fleeting thought.

He started toward it at a casual pace, drawing his revolver, a formidable Smith & Wesson Schofield .45. From the outside, the building looked deserted. The windows were boarded and the door stuck partially open at an angle in the rough dirt. No horses were reined anywhere near it, and no sign of life.

A hawk circled over Fort Mason, soaring on the wind currents, searching out prey. It cried out once, the sound echoing across the sky, before swooping down the hillside and out of sight.

Hawthorne heard a noise inside the brig, a soft shuffling of boots, and the unmistakable click of a gun hammer being drawn back.

A slow, nasty smile spread across Hawthorne's narrow face. He took another step, and then kicked in the door with one well-worn boot.