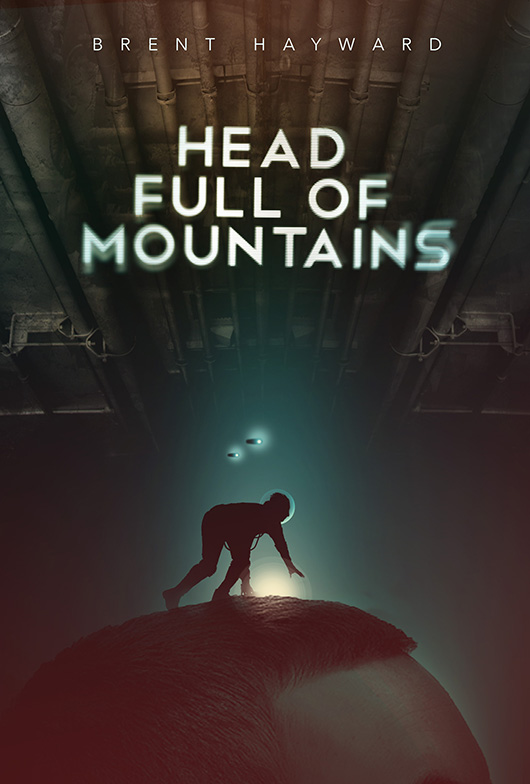

Head Full of Mountains

Read Head Full of Mountains Online

Authors: Brent Hayward

MOUNTAINS

BRENT HAYWARD

ChiZine Publications

To memories of R. E. Hayward, 1930–2011

When James Calvert went out as a missionary to the cannibals of the Fiji Islands, the ship captain tried to turn him back, saying, “You will lose your life and the lives of those with you if you go among such savages.” To that, Calvert replied, “We died before we came here.”

—David Augsburger,

Sticking My Neck Out

From porthole of the harrier was an image of desolation but once, father said—before he got too sick to talk any sense—there had been a line of something called

mountains

. This was well before the womb expelled Crospinal, before father found refuge in the pen and tethered himself to the capricious world. And not viewed out this particular lens, up in the harrier’s console, but from another, peered through during his frantic search for a refuge. Crospinal tried imagining these mountains now—

magnificent,

his dad would say, a tear in his eye, every time he reminisced—as Crospinal had tried imagining them many times throughout his dozen or so years of life, conjuring several possible and incongruous visions of the aberrations. Yet he failed, as always, not only because of the limitations of his imagination but because he was no longer sure he

believed

in such things, whatever they might have once been.

Despite his obvious infirmities, Crospinal had managed the climb up seven rusty ladders to the harrier console perhaps a hundredfold—when he’d first discovered it, as many as three times a day—to loiter here, among other pastimes, straining his eyes through the thick, etched polymethyl: all he ever saw out there was the eternal grey flatline of ash, with a paring of orange at the horizon—some orb or other, whether rising or sinking was impossible to tell.

Rumblings, coming up from the floor grille, and through the thin soles of his boots—and what sounded like a dim explosion of sorts, possibly the engines misfiring—made the world shake lightly. Dustings of dry polymer from the composite panels settled over him. Crospinal picked at his nose, making capillaries in his mitt tingle as they tried to deal with the crusted mucus he rolled between his thumb and forefinger.

He watched out the porthole a moment longer.

To doubt the word of father

, Crospinal thought.

Was that how it all began

?

Glittering, refracted through the plastic, watered his eyes. When he turned aside, green after-images of the occluded orb remained, but he tried to blink them away—

The controller, well accustomed to Crospinal’s moods and brooding self-indulgences, expended little energy on recent visits, though it faced him now—a grey sphere, the size of his eye—without speaking, having dropped from the ceiling to hover at the exact epicentre of the small chamber; Crospinal frowned, hoping the controller would go back to where it came from, or at least remain silent (the latter of which, thankfully, it did). Crospinal looked away first. The controller continued to study him.

He fidgeted, getting tense.

Time he’d spent dreaming had not, evidently, driven away doubts, nor kept them at bay for even the shortest of whiles: scents inside the dream cabinet had been weak today, vapours thin and vague, and the dream, when it finally pulled him under, was so inconsequential that details were now entirely forgotten. Therapeutic value, nil.

Crospinal lifted the console's cover and flipped it back. The gently rotating image rose from between the holes—two hands, pressed together—and then wavered. Without much further consideration, he shoved both forearms deep inside, felt the connection, a shudder passing through the Dacron of his mitts, up through his skin, into his bones, building in strength. He said, too desperately for his own liking, “Are you there? I know you might be . . . busy. But can you visit? Just for a second? I wanna tell you something.”

Nothing. Unfathomable energies of the world went about their business, as they did, passing through him, on their way from father’s range out into landscapes Crospinal had not yet travelled and landscapes he never would. Crospinal had been stalling. Dark ideas and memories of rejection were too recent, and daunting; his girlfriend showed up less and less anyhow. And when she did show, she seemed distracted, distant, almost incohesive, if that was possible. Silent. Crospinal wanted to feel angry at this life of pain and the vagaries of phantoms but instead felt the same dullness spreading through him that was always there, as if his damaged nerves were trapped, keening on some standing wavelength between the surface of his epidermis and the snug lining of his sleeves. His molars sang. Under the thin shield, fountained by the uniform’s collar, to cover his head, sparks crawled through the stubble of his recently depilated scalp.

Nothing.

About to withdraw, give up, return to the lower floor, there to get on with killing time, Crospinal saw her at last, flickering faintly, becoming almost opaque, positioned so she seemed to be sitting on the ill-formed shelf to his left. (Though a good part of the structure penetrated her hip. Or vice versa. Most days, Crospinal could easily ignore these minor aberrances. He was used to them. A second of his girlfriend’s attention made everything worthwhile, and he was outnumbered anyway by entities that could transcend such mundane physical collisions.)

Dressed, as always, in a fresh, dark uniform, similar to his own but heavier, with a circular collar, like no uniform any dispenser had ever offered. With breast pockets, too, tinted mitts, no helmet. She wasn’t facing him. Made of light, of course. His girlfriend had a glow to her, a faint pixilation, an allure that always caught his breath. He could smell her energy. Around him now, an aura of faint ghosts circled.

“Hi.” He managed to speak, heart fluttering, as if this meeting, like all other meetings, were their first. “I, uh, father’s still sick. He’s

really

sick. I mean, his bones are so, you know? And he won’t stop coughing.” Crospinal had not meant to say these things. He never did. But the keening he carried around came forth nonetheless, propelled by a force within him bent, no doubt, on sabotaging what might be considered his best interests. The plan had been to remain positive, to impress, to make this beautiful manifestation laugh and regain her dwindling affections. A simple plan, but already messed up. He cleared his throat and tried, for a moment, without luck, to think of a recovery line, or endearing witticism. “I’ve been over, uh, to the—”

His girlfriend had not yet responded.

She had not even moved

. Crospinal stopped talking.

Was she okay?

Posed there, wavering

a bit, wavelengths faltering, her hair pulled back so tight that the corners of her eyes tugged, all squinty.

She had not moved.

He wanted to take his hands out of the holes, touch her, hold her, pull her close, wanted to do these things so much they were an awful ache that had settled into his core ever since he’d met her: that ache flared now, but his girlfriend would vanish long before he could lift a finger. His hands—if she were able, by some miracle, to stay—would pass right through her.

“Have I done something wrong? Upset you?”

Frozen there in such a way that she, too, seemed to be looking out harrier’s porthole, at the ash beyond. The profile of her cheek, her nose, a narrowing of her eyes, all through a shield, was enough to cause Crospinal duress. A slight flickering, overall, but no movement. (Was it possible—her seeing anything, that is, outside? The horizon, blown across by hot winds, the curve of a reddened orb burning across the sky? Like he saw, every time he looked out. Could she see it? He’d never asked, though he broached nearly every other topic. She had heard him blubber, confess, profess, ramble. Once even heard him laugh. Had waited patiently while he stared down at his own boots, too morose to speak.

Would asking his girlfriend about the horizon outside, and the possibility of mountains, sully the only tie remaining between him and his ailing father? Would he be cast further adrift, or was the damage already done?)

“Why you so quiet?” His own words a whisper. “What’s up? I . . .” All this time his beleaguered heart had been lugging something heavy up his throat to his mouth, to dump it there, like refuse. He could not swallow. Slower poundings in his chest. “I, uh, I’m—

Shit.

Things are falling apart. I’m, well, I’m

scared

.” Another long silence. On his part, growing despair. Anxiety.

Could girlfriends cease? Everything else seemed to, so why not—

Mercifully, though, stuttering to life (such as it was), moving one arm, turning toward him, to engage—

Consumed by relief, as their eyes met, Crospinal felt such a rush, and he grinned idiotically, though he knew already what was coming.

“Don’t call me anymore.” She was smiling. “I thought we had that clear.”

The ghosts whirled and faded.

Elation, which he only wanted to nurture, maybe even let soar, like it had done at rare but glorious times in the past, plunged and crashed. Maybe his body was the one assembled out of photons, and projected here, not hers. Maybe he was unsubstantial. He said:

“What?”

“Your memory’s atrocious.” Still smiling. (Him being flayed alive by it.) “This area’s being subsumed. The influence of your passenger’s waning. You need to leave. But you don’t need me anymore. Remember? You promised. So I came here, one last time, to remind you. You need to leave.”

“But I—”

What had he promised?

He wanted to say he loved her, and that he missed her, and that he needed to be with her forever. But those sorts of statements had already precipitated trouble.

“Time for you to leave, Crospinal.”

Seldom did she say his name. It invoked hot torrents in him. He swallowed—hard—at last. “But there’s nowhere to go.”

Narrowing her eyes in that lovely way of hers, glazed and unfocussed, she said, “They’re searching for you.” Her lips—also exquisite—were not quite synced with the words that tore Crospinal apart like teeth of the hardest polycarbonate. “Don’t call me anymore. Don’t come back here. For both of us.”

“Who’s searching for me?”

A hint of movement passed though the space that would be behind his girlfriend, were she sharing his realm: slim dark shapes shifted through the composite that comprised the counter—

And Crospinal was alone again.

The empty harrier console. Stupid controller, hovering there, watching.

“I suppose you were talking to your girlfriend again?” it said.

“Shut up.” Glare, from outside, stinging Crospinal’s eyes. “You’re just mad because you’re fading, too. ’Cause this station’s going.”

“I’ll relocate. I’m due for a transfer.”

Dragging his forearms clear of the holes, Crospinal stood for some time, feeling utterly gutted.

Later, returning home, he stomped in his bow-legged way along the catwalks and narrow grates that had emerged when he was born, and solidified when he was a young child, but were now starting to crumble. Knees popping, he kicked at debris, knocking fractured chunks and residue of the formations through the grille onto dimmer structures below.

As soon as he got within father’s range—smaller even than yesterday—a dog coalesced, and tried to cut off his passage.

“Crospie,” it barked. “Crospie! Crospie! Nice to see you back! But you’re making too much noise. Welcome back! All that clattering! Ringing about. Could have threaded that bolt back on. We saw you kick it. We saw you! Could have helped. Stem the tide, you know? Remember when you were showed? Remember that, Crospie? Remember? About bolts? The haptic about nuts and bolts and metal?”

“Go away, dog. That wasn’t a bolt. Just some hardened polymer crap. I was doing you a favour. Keeping entropy at bay.”

“If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. Remember?”

Crospinal stopped. “Father says a lot of things like that. You should know. It doesn’t mean anything. And I suppose you’re part of the solution? All you dogs and spirits and shit? Floating around. Can you leave me alone? And

you’re

the one making too much noise. Yapping all the time. You make

way

more noise than me.”

He kicked, but half-heartedly: the dog easily dodged. Both the kick and the dodge were pointless. Now the apparition looked up through narrowed eyes of light.

“What’s gotten into you? You’ve changed so much. What goes on out there?”

“Father has no idea where I am. Even if I’m standing right in front of his face. He’s so out of it. He has no idea if he’s awake or asleep. Now leave me alone.”

At the remote end of the hall, other apparitions appeared.

“Call off your stupid friends. I’m fine. Go back to your kennels. Go back inside his head.”

The dog cocked its own to one side, sniffing. “Were you crying again, Crospie?” The second kick would have passed right through it, had reactions been any different. Moving in to mock-sniff again at Crospinal’s boot, the dog—all dogs, all apparitions, and father, too, lost in the abyss of his ailment—knew, that instant, the truth.

Crospinal resumed walking. Stoic, bones protesting, knees akimbo, heart heavy.

The little apparition caught up, and trotted next to him.

No dog could stay quiet for long.

“It’s okay, Crospie. People cry. That’s what you do. You cry, eat, worry, sleep.

Dream.

Lie awake, trying to remember. You should talk to us more. We’re here for you. We

worry

about you. We don’t know where you go anymore. We don’t, Crospie. We don’t, and we worry.”