Heart of Coal

Authors: Jenny Pattrick

EIGHTEEN YEARS HAVE PASSED SINCE THE CHILD ROSE ARRIVED ON DENNISTON, RIDING UP THE TERRIFYING INCLINE ON A STORMY NIGHT.

She has now grown into a young woman, intelligent and talented, with an outrageous zest for life. The trauma of her early years seems forgotten, though some recognise its shadow in her often unconventional behaviour. Rose is expected to marry her childhood friend the golden Michael Hanratty, but when dark and stubborn Brennan Scobie arrives back on the Hill after a seven-year absence, a challenge is inevitable.

This sequel to the bestselling

The Denniston Rose

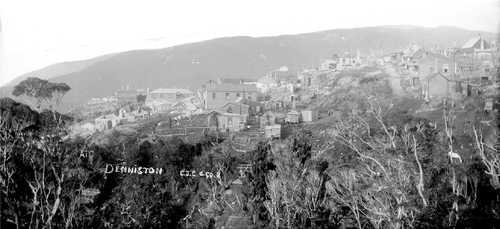

continues the fortunes of the remote West Coast coal-mining settlement. At the turn of the century Denniston is still isolated, but all that is about to change.

Heart of Coal

is about loss and love, hope and despair. It is a story of convention and the lack of it and of the uncompromising spirit of a unique woman.

For Lynn, Tim and Simon

with love and respect

Oh there’s plenty of English Roses

And there’s Mary, the Rose of Tralee

But the Denniston Rose was a Coaster —

Wild and thorny and free.

She arrived on the Hill in a blizzard

No more than a tiny nipper

As tough as a boot our Rosie was

And as pretty as a slipper.

She was trickier than Donnelly;

Light-fingered too, they say

She’d winkle a shillun’ out of your purse

While she bade you a sweet ‘Good day’.

She killed a man with her own bare hands,

She started a miners’ riot,

Then ran off to Hokitika

When she fancied a change of diet.

A law unto herself was Rose,

She came and went at will,

From north to south she travelled the Coast

But her heart was on the Hill.

Oh there’s plenty of English Roses

And there’s Mary, the Rose of Tralee

But the Denniston Rose was one of us

It’s the Denniston Rose for me!

West Coast ballad

OMENS WERE ALWAYS taken seriously on the Hill, and looking back you could say the omens were not good. Two wagons derailed and a near gassing in the mine within twenty-four hours of Brennan’s arrival. Hindsight, of course, is an easy card to play. At the time it was all cheering and celebration the day the Scobies returned after an eight-year absence. Henry Stringer, always ready to voice an opinion, may have predicted trouble. Trouble, yes — but death? Suicide? If suicide could be believed. No one predicted the suicide. Even with the evidence — the rope, the body, there for all to see: the bulging eyes, the purple tongue — not one person on the Hill (except perhaps Henry Stringer, who never told) could truthfully claim to understand the why of it.

Bella Rasmussen saw the problems too, that first day, the evening of the celebration. But she never saw the difficulty as insurmountable.

Who did? When dark Brennan turned up with the Josiah Scobies, Bella said she trusted her Rose to sort things out. Mind you, that indomitable Queen of the Camp had always been one-eyed over Rose. Or loyal might be the better word. However fiercely arguments might rage inside the old log house, she would never speak ill of Rose in public. ‘No, no!’ she would cry, shaking her plump hands and laughing to dispel any criticism, ‘I will hear no word against my Rose! She is just a spirited woman and good in her heart. A mother knows her daughter.’ This last said with pride. She was in fact stepmother, though not many remembered this, and those who did preferred to forget that other terrible mother who had brought Rose to the Hill back in the early days. Black days for Rose, and best forgotten.

And Rose herself? Did she predict disaster that night, shortly before the century turned? Surely not. She would have joined in the fun, laughed and clapped at the antics, and thought no more of it.

SO here come the Josiah Scobies, Mr and Mrs Important from Wellington, with their talented youngest son, back to Denniston for a day or two, to help celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the opening of the Denniston Incline. Mary Scobie is already regretting her decision to attend. The steamer trip from Wellington was a nightmare. Southerly swells to dwarf a house, and then a wait of five hours steaming back and forth until the captain judged the bar crossing safe. Now at least there is better weather for their ride on the coal train up from Westport. The Scobies sit in a proper carriage, hitched at the back of a long row of empty clanging coal wagons. Up the coastal strip they chug, enjoying the warm spring sun, listening with half an ear to eager officials who detail production increases and mining improvements since Josiah and his family worked underground up on the plateau. Josiah nods, makes an

alteration to his speech notes, nods again, but his mind is more on the landscape. The train has turned inland now and puffs up the dark gorge, hauling wagons and passengers around narrow bends above the Waimangaroa River, where tree ferns cling to steep walls and fat wood-pigeons flash blue-green-white in the sun. Josiah shifts his broad miner’s shoulders inside the tight cloth of his city suit. He smiles to see the black seams of coal outcropping on the sheer cliffs and to remember tough, proud years working underground with his brothers and sons. To be honest, he’s looking forward to spending a night or two on the high plateau with the smell of coal in his nostrils. Premier Seddon is a fine man to work for, but a hand cramped from writing regulations is sometimes a poor substitute for a top hewer’s aching shoulders.

No such anticipation for Mary Scobie. She sits straight-backed and formidable, fashionable fur at wrist and collar, ostrich feathers sweeping over her hat. She nods at the man from the Westport Coal Company, because it is expected of her as wife of a Government Man, but she would much rather be back in Wellington immersed in her beloved committees, arguing and cajoling in rooms where a strong voice can make a difference. Certainly it will be a pleasure to see the Arnold Scobies again, but overriding that eagerness is a niggling anxiety. Mary is well aware that Brennan, sitting opposite her, is wound tight as a spring. These last weeks, since the invitation came, her usually quiet son has shown flashes of determination that have surprised her. Mary had suggested that his musical commitments in Wellington should take precedence over an invitation to play for the tiny Denniston community. Brennan said nothing at the time, but later she discovered he had cancelled those commitments without consulting her. Even the engagement to perform for the Temperance gala! Then he wrote with his own hand, against her express wishes, accepting the call to Denniston. Last week Mary

happened to glance at a crumpled note, discarded in Brennan’s room, and found it addressed to Rose. A simple letter of friendship perhaps, but still disturbing to Mary. She had assumed Brennan had forgotten his old friends on the Hill and was happily settled into his Wellington life. Mary has lost three of her six sons to the coal — Samuel to Denniston, irretrievably interred beneath a cave-in the very year they arrived on the Hill; Mathew and David five years ago at the Brunner disaster. This last almost broke her. When Mary had realised she could never persuade her two older boys to give up mining she had begged them at least to leave the Hill for the ‘safer’ life and conditions at Brunnerton: closer to hospital, nearer to the more civilised town of Greymouth. The boys had been persuaded, only to die a year later, buried alive along with their mates in that terrible underground explosion — an accident that would never have happened in the gas-free Denniston mines. Mary now lives daily with that weight of guilt and loss. Over her dead body will any of her other three sons take shovel or drill underground.

‘Settle down, son,’ she says now to this beloved Brennan, ‘or you will be too on-edge to play.’ But she smiles to see his fingers dancing a tune on the hard black case of his cornet. Oh, what plans she has for him! Qualified engineer and champion cornet. This one will go far.

A shriek or two from up front announces their imminent arrival at Conn’s Creek. The engine, slowing to a halt, disappears under clouds of steam. Brennan is out of the carriage before his parents are halfway to the step. He runs up past the waiting line of full coal wagons and hails one of the truckers.

‘Hooter! Hooter Harries, is that you then?’

The fellow runs an empty wagon forward, then looks up. The high whinnying laugh that earns him his name echoes off the stone walls. ‘By God, it’s Brennan Scobie, grown up into a smart

town suit! Come to lord it over your old mates, eh?’

The sting in the words is unexpected. Brennan shrugs, grins, shuffles his feet.

‘Well now,’ says Hooter, laying down the challenge. ‘Will you be riding up in this empty here or have you lost the taste for it?’

Brennan looks around to see who might be watching. He’s keen enough. ‘Surely it’s not allowed?’

‘When was it ever? We still ride the wagons, though. The boss is up the track a bit. Hop in this one when I’ve got it coupled.’

Brennan tilts his head to look up the sheer length of the Incline. High above he can see a full wagon descending to Middle Brake. He watches the empty one pass it where the rails split for a few chain, and then, pulled upwards by the same cable that lowers the full one, it rattles on up, up, nearly vertical, to disappear over the edge of the plateau, 2000 feet above.

Brennan is itching to be up there. ‘You’re on, Hoot,’ he says, ‘if you can smuggle me aboard.’

But Mary Scobie is calling, ‘I need you to carry my bag, son; I will be lucky enough to walk the track without any extra weight.’

Brennan goes over to her. Josiah is preparing for the walk up, loading a case either side of the pony that will take their larger luggage up the narrow, winding track.

‘Mother,’ says Brennan quietly, ‘Hooter, here, will load me into an empty. I’ll take your bag with me.’ He reaches for the bag but Mary snatches her hand away. The fearsome Incline has always been a dark enemy to Mary Scobie. Seventeen years ago this tough daughter and granddaughter of English Midlands miners, having survived three months at sea with six children on the voyage to New Zealand, had been reduced to a quivering mess — had shamefully wet herself — riding a rackety empty coal wagon up that vile deathtrap of an Incline to her new life on the plateau. The same year

another wagon had carried the body of Josiah’s youngest brother, killed in the mines, down to burial far below. The mourners had to stand up on that bleak plateau and watch the coffin scream on down as if it were another load of coal to the yards. For those years when Mary had lived on the Hill, trapped, fearful for the very lives of her sons and husband, the Incline was symbol of all the worst about Denniston. The tyranny of that isolation.

‘You’ll not ride that Incline, son. Not now; not ever!’ booms Mary, her voice turning heads all down the yard. Brennan lowers his head. He is trembling but stands his ground. Further away Hooter watches.

But suddenly all attention is elsewhere. There is a shout from above. Mary Scobie looks up. Around her, men are already running. It is as if her own fears have generated a dire power of their own. Above them, a short distance up the Incline, a coupling has come adrift from the ascending wagon. The great wire cable, released from its enormous tension, leaps into the air. Its heavy steel hook snakes across the tracks as if a giant is fly-fishing. A maintenance man up there is stumbling, zigzagging, trying to dodge the flailing hook. The watchers below shout to see the man caught on the back-swing and flung into the bush like a rag doll. There’s nothing can be done but watch. Meanwhile the empty wagon, the very one Brennan might have ridden, is no longer being pulled upwards. Perhaps it was insecurely fastened during Hooter’s exchange with Brennan. For an agonising moment the wagon hangs there. Then gravity takes over: it rolls backwards, gathering speed.

Josiah drags a transfixed Mary into the lee of a shed. Hooter and the other yard men can do nothing. Who knows where the wagon will derail? Down it roars, beginning to rock now on its iron wheels.

‘It’ll come off at the bridge!’ shouts Josiah. ‘It has too much

sway on to make the yard.’

And he’s right. At the bridge near the bottom of the Incline the wagon fails to take the curve, crashes through the iron railing as if it were kindling, and hurls itself down into the gully. Clang, clang, they hear it meet with the rusting hulks of former disasters.

Two men are already climbing the sleepers to see to the injured maintenance man when a series of high shrieks has everyone jumping. The train driver is hitting his whistle to signal a more serious threat. From his higher vantage point in the cab he can see the full wagon coming. The brake-man at Middle Brake has failed to control the loose cable. The jerk and change in tension has dislodged the hook or snapped the cable on the descending wagon. Oh, Jesus, here comes the full wagon, its wheels screaming like a banshee: ten tons of coal and iron, unchecked and lethal. Down it careers, past the two men who have jumped to the side and are now buffeted to the ground by the wash; down to the bridge and across, the heavier weight keeping traction with the rails; down to the yards where everyone has taken what cover they may. The engine driver, good captain, stays with his engine.

‘Brennan! Where is he?’ cries Mary Scobie, all her city certainty flown. ‘Oh God Almighty, this damned place is our doom!’

But Brennan is safe at the bottom of the track, holding the pony’s head. He sees the full wagon roar into the yards. He watches as men break from cover like startled birds when it seems the wagon is headed their way. But it misses the signal hut by yards, leaps the track, teeters for a good chain on one set of wheels, past empty wagons, well clear, thank God, of the steaming engine, then skids on its side over the ledge and down, cartwheeling through the bush, on into the gorge, its spilt coal laying a black blanket over the gouged earth.

In the sudden silence Mary calls out wildly. Her ringing voice,

accustomed these days to a public platform, echoes madly in the sudden calm. ‘Brennan! Brennan!’ Fury rather than concern seems to be fuelling her. ‘Brennan!’

The boy appears quietly, leading the pony. ‘And you would have ridden that death-trap?’ she shouts. ‘Oh, you fool, when will you grow up?’

‘It’s all right, Mother, I’m safe,’ murmurs Brennan.

‘That is not the point!’ shouts Mary, but of course it is. She turns her head to hide the weak tears.

Those who hear the exchange are embarrassed. A good man may be lying dead above them, and she rails at her boy as if he were a toddler.

Josiah lays a hand on his son’s shoulder. ‘I’ll stay to see if I can help,’ he says. ‘Best to take Mother out of all this. Leave the pony, I’ll bring it up shortly.’ He sighs. ‘Not the best start to a week of celebration. It would seem conditions have changed little.’

Brennan can say nothing. He takes his mother’s bag, aims a lighthearted shrug in Hooter’s direction and is hurt to hear that derisory laugh ring out again.

As he plods up the Track behind his mother, Brennan rehearses speeches in his mind. The encounter — not with the runaway wagon but with his mother — has shaken him. If he can’t gainsay her on small matters, how is he to manage the next few days and all he has planned? His mother stops to puff. Her face is red and agonised, her chest heaving inside the tight bodice.

‘Oh, Brennan,’ she gasps, ‘I had forgotten how far it is! You would surely think that by now some better access was in place. It is a scandal!’ Already she is planning a word to Premier Seddon, who is a personal friend.

Brennan turns on the narrow path to look back. Far out to sea a dark line of cloud signals an approaching storm, but they should

reach the settlement before rain arrives. He scuffs his feet, impatient to run ahead but trapped behind his mother’s tortured ascent. His plodding feet beat time to a silent song with a single word: Rose, Rose, Rose, Rose. The eight-year-old memory of her that he has cherished every day of his exile in Wellington still burns bright and hopeful. He knows that the tall fourteen-year-old he remembers, with her bright curls and wide smile, her habit of picking up her skirts and running on bare feet like a boy — he knows this Rose is now a woman. But in her letters she is still the same exciting and dangerous friend.