Heat (21 page)

Authors: Bill Streever

I wander out into the yard, looking for boilers and stockpiles of coal. Instead I find the steam train locked in a shed of rusting sheet metal. I can see the engine through an opening in the shed’s doors. It is not a full-sized engine but a small-gauge train, for tourists, painted green, a toy for steam lovers.

I go back to the docent, still perched on his chair, unmoving. I ask where the new boilers are, and the coal stockpiles. “We don’t burn coal anymore,” he says. “The boilers run on gas now. The city will not allow the burning of coal.” The boiler room is not part of the exhibit. It is off-limits.

“What about the train?” I ask. He assures me that the train, when it runs, runs on coal. The coal, he tells me, comes from Poland.

Back in Anchorage, I burn wood in a metal fire pit behind my house. I build a bed of red-hot coals. On top of this, to the right, I place my pilfered brick of peat. To the left, I place my pilfered coal. With my infrared thermometer, I shoot a reading. The red-hot coals of burned wood, now flameless, hit a thousand degrees. The tops of the block of pilfered peat and the pilfered coal remain, for now, cool and lifeless, at sixty-five degrees.

Within a minute the peat flares, first at one end, then the other, but the flames disappear as quickly as they appear, leaving behind a red glow that consumes individual fibers. With my bellows, I blow air across the peat. The fibers ignite. In their flames, I see strata in the peat, layers of long-dead vegetation, each layer perhaps a year of growth. I count fifteen layers in the flames.

The temperature of the flames: 1,100 degrees.

The coal remains quiescent, holding on to its carbon. I encourage it with the bellows. It begins to glow. As it warms, jets of flame ignite around it, flares of vapor. I encourage it further, pumping air across it. At two minutes, it develops a steady red glow. It sends out more flares. I continue pumping. At three minutes, it produces a steady flame. It becomes a rock on fire.

The temperature of the burning rock: 1,200 degrees.

I add wood to the fire pit, separate from the peat and separate from the coal. The wood flares up within seconds. I have before me fires of wood and peat and coal. The important difference between these fuels is not so much the temperature of their flames. That temperature changes by the second, reacting to changes in wind and moisture and any number of realities. The important difference is in the amount of heat they put out per weight burned. Coal—even low-quality coal, lignite, one step removed from peat—wins. A pound of coal produces twice the heat of a pound of wood. Wood and peat, on the other hand, match each other. Peat, dry, is not much different from wood. But at times, and in places, peat was abundant when wood was not.

Even this single tiny lump of burning coal noticeably taints the aroma of wood and peat smoke. My dog, who loves company, sniffs the air, stands up, stretches, and goes inside alone, tail down and ears tight against his head. I bend over, closing in on the coal to smell its raw fumes, to inhale acrid smoke. It smells unpleasant in the extreme, not the sulfur of rotting eggs but something more sinister, a smell that assaults the nostrils, reminiscent of hot tar.

If a smell can be bitter, the smell is bitter. If a smell can be black, the smell is black. It is the smell of nineteenth-century London. It is a smell that would have been familiar to James Watt and George Stephenson and Ralph Waldo Emerson and Charles Dickens. It was, at one time, the smell of progress.

I

n the 1850s, people burned wood and peat and coal for heat, but they had more choices for lighting. Most people burned candles, but they also used oil-burning lamps. The wealthy burned sperm whale oil, the less wealthy burned the brown oil from bowhead whales, and the even less wealthy burned the fat from pigs. For those willing to risk explosion and fire, there was light from lanterns fueled by camphene, which was distilled from turpentine, which came from pine sap. Some cities used town gas, a mix of hydrogen, methane, and the various other hydrocarbon gases that came from coal and was piped into street lamps and homes. By the 1850s, people occasionally burned kerosene in lamps. At that time, kerosene, like town gas, was refined from coal. Kerosene lamps had certain advantages, but kerosene from coal was expensive.

In the early nineteenth century, oil from seeps in western Pennsylvania, in a region that was home to the Seneca Indians, was soaked up in rags or skimmed from creeks that flowed near the seeps. Rural entrepreneurs dug pits and trenches to increase their take. In this way, a day’s labor could yield a few gallons. The fluid came from the earth and was known generically as rock oil or Seneca Oil.

At first, rock oil was not burned. It was sold as a cure for toothaches, headaches, stomach pains, worms, rheumatism, and deafness. The limited medicinal properties it possessed were exaggerated to the point of hyperbole. From an advertisement for Seneca Oil:

The healthful balm, from nature’s secret spring,

the bloom of health and life to man will bring;

As from her depths the magic fluid flows,

To calm our sufferings and assuage our woes.

In the early 1850s, a man named George Bissell, an entrepreneur by nature and economic necessity, acquired a quantity of the healthful balm and realized that it might be burned as an illuminant. He pulled together investors and hired one Professor Silliman to write a report on rock oil. Silliman’s experiments occasionally caught fire, but he reported “success in the use of distillate product of Rock Oil as an illuminator” and described refining methods.

“It appears to me,” Professor Silliman wrote, “that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your Company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive process, they may manufacture very valuable products.”

Professor Silliman understated the facts. What the company had in its possession was a substance that would change the world. The molecules of petroleum carried energy efficiently and conveniently. But to change the world and to enrich himself and his investors, Bissell needed to find the stuff in quantity. He needed to get more rock oil out of the ground.

Bissell and his investors hired Edwin Drake, formerly a conductor for the New York and New Haven Railroad, a man whose chief qualifications were his amiable nature and the fact that he was unemployed. He stood tall, dressed well, and had large eyes that often conveyed a sense of deep thought and intense interest. A portrait suggests that he was heterochromic, his left eye darker than his right. Bissell dubbed him “Colonel Drake” to add an air of respectability and sent him to what was then the hinterlands of Pennsylvania, to a place called Titusville. It was May 1858, and Titusville was a logging community near the oil seeps, population 125. After having visited Titusville, one of Bissell’s investors called it “the most forsaken place I was ever in.” The investor commented, too, on the mud, which would, after Drake’s success, become a popular theme in written accounts.

With his wife and child, Drake moved into a Titusville hotel. The hotel was known to the locals as “the tavern.”

“I found it a rough place for a residence,” Drake later wrote, “but with my family around me I was happy.”

Drake hired men who worked the creeks and repaired existing trenches and pits. For their trouble, they harvested a few barrels in a season. Soaking oil into rags or skimming it from the surfaces of creeks was no way to get rich.

Someone—probably Bissell, but possibly Drake—remembered an advertisement for medicinal Seneca Oil, specifically for the bottled medicine sold as Kier’s Petroleum. The advertisement showed drilling rigs of the kind used to drill for salt, an ancient practice that had been adopted in the salt-rich lands of western Pennsylvania. Kier’s Petroleum came up with brine from wells near Titusville. Kier was for the most part after the brine, from which he harvested salt. He and the other salt drillers usually threw away the oil, dumping it into pits or rivers. But Kier’s wife was treated for tuberculosis in 1848 with a prescription for American Medicinal Oil, which came from a salt well in Kentucky, and Kier recognized the stuff in the bottle. He started bottling medicinal oil from his own wells. For a decade before Drake arrived in Titusville, Kier had been saving some of his oil and bottling it as medicine, to be taken externally, as a liniment, or internally. Before Drake arrived in Titusville, Kier had sold almost 240,000 bottles of rock oil in half-pint medicine bottles.

Bissell and Drake, influenced by Kier’s advertisement with its sketch of the salt wells, decided to drill. They decided to drill for rock oil—not for salt with rock oil as a by-product but for the oil itself.

Drake had trouble finding a qualified driller. The problem was not an absence of drillers but an absence of drillers willing to work for Drake. In western Pennsylvania, drillers were too busy drilling for salt. Several of them told Drake that they would come to Titusville to drill but never showed up. At least one driller promised to come to Titusville for no other reason than to get rid of Drake, to get Drake to leave him alone. The driller thought that anyone intentionally drilling for oil must be a nut. Oil was not a valuable commodity. Oil was a nuisance. It ruined salt wells.

The drillers, Drake wrote, “were thirsty souls and preferred Whiskey to any other liquid for a steady drink.”

Drake persevered. He was later remembered as quiet and reserved, “never boasting or bragging about the great things he expected to do.” He seldom swore. He seldom drank. Money was a problem. The investors, initially enthusiastic, did not always come through with funds for legitimate expenses. Drake was not fully paid his agreed-on salary. But his reputation for persistence grew. A local businessman loaned him money on little more than his word, and Drake got by.

Still searching for a driller, Drake hired men to dig into the earth, to dig a well. The well they dug flooded.

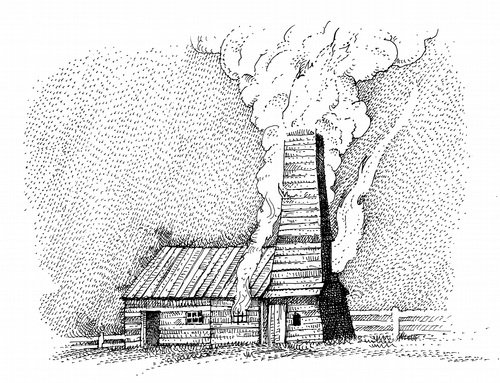

Drake acquired a steam engine, paying for it in installments. He built an engine house. But still he was without a driller.

In April 1859, Drake heard of another driller. The driller was working in the town of Salina, near Tarentum. The driller’s name was William Andrew Smith, but he was known as Uncle Billy. He was not purely a driller. He was a man who could fix salt well problems, but at the time he was working as a blacksmith and planning to reinvent himself as a farmer. Instead he went to work for Drake. Their agreed-on salary: $2.50 per day, with Smith’s sixteen-year-old son thrown in gratis. Smith’s wife refused to go. Titusville, to the cosmopolitans of Salina, was the backwoods. In need of a cook and housekeeper, Smith turned to his daughter Margaret, age twenty-four.

“When I first saw Colonel Drake,” Margaret later wrote, “he had on a black suit and a high black hat. He was naturally a dark-complexioned man. And the black hat and the black clothes made him look all the darker. After he had gone I remember saying to my father, ‘That man looks like an Indian.’”

Margaret worried out loud that they might all be killed.

But instead of being killed, they moved into the engine house that Drake had built. The frogs kept Margaret awake at night. Drake and Smith raised a derrick. The derrick, like the engine house, was made from rough lumber, unpainted. It was twelve feet on each side at its base, tapering to three feet on each side at its top. It was built lying down, on its side. With the help of sawmill workers and the scattered neighbors of Titusville, Drake and Smith tipped the derrick upright.

Smith’s wife and an additional four children joined him in July. Before it was over, all of Smith’s children would work on the well. The method they used was not modern-day rotary drilling. They were not drilling in the same sense that one would drill a hole in a plank. They were drilling in the sense of drilling with a nail—of banging a nail into a plank, then removing the nail to leave behind a hole. They were pounding and chipping, using a method variously known as cable drilling or cable-tool drilling or percussion drilling or cable-tool percussion drilling.

They started with a pit. The pit was about eight feet deep, reinforced by logs. In the bottom of this pit, they drilled. A rope dangling from the top of the derrick held the drill bit, which was in fact a heavy chisel. Smith had made the bit—the chisel—with his own hands. The principle was simple: lift the bit and let it drop, lift the bit and let it drop, lift the bit and let it drop. The steam engine’s power—power derived from burning wood—lifted the bit. Gravity drove the downward drop. Each time the bit dropped, the well grew deeper, a sliver of earth chipped away. Periodically, the bit was lifted clear of the hole, and a scoop was lowered to remove chipped rock.

At sixteen feet, they struck water.

Smith rigged a pump, but knee-deep water in the pit slowed progress. The pit collapsed. Someone—maybe Drake, maybe Smith, maybe someone else—suggested driving a pipe into the existing hole to protect it from cave-ins and to slow down the water. The method had been used before the Drake well, but the idea seems to have been new to the men in attendance. They lined their sixteen feet of bore hole with two lengths of cast-iron pipe. Drake acquired additional pipe. They drove the pipe into the ground. At a depth of forty-nine feet and eight inches, they struck rock. The bore hole was now lined with pipe all the way to a layer of solid rock, so it would neither collapse nor flood.

Through the lining of cast iron, they drilled deeper. Lift the bit and let it drop, lift the bit and let it drop, lift the bit and let it drop. Eight hundred and fifty pounds of drilling gear went up and down, pounding and chipping through the pipe, through the cast-iron casing, cutting its way toward the fat of the land.

By this point, Drake had more or less stopped paying his bills. In late August, Drake’s investors sent him a letter telling him to abandon the well, to close up shop. They gave him five hundred dollars to cover the costs of shutting down. But in 1859 the mail to Titusville moved no faster than a horse could walk. Drake and Smith kept lifting and dropping, lifting and dropping.

On Saturday, August 27, 1859, they reached a depth of sixty-nine feet. Without warning, the drill bit dropped six inches. It had hit a void in the rock, a soft spot. They called it a day.

The next day, the Sabbath, a day of rest, Uncle Billy Smith realized that the void was full of oil. They had struck oil in the bottom of Drake’s well.

Smith replaced the drilling gear with a pump. The pump, in the bottom of the well, was connected to the surface by iron sucker rods. The sucker rods were connected to the walking beam, which was connected to the steam engine. The exciting business of exploring for oil was replaced by the dull routine of production, of pumping, the steady chugging of the engine and the splashing of the oil at a rate, at first, of ten barrels a day.

Derricks sprung up around Titusville, a new kind of forest. Kerosene distilled from rock oil became rather suddenly available in large quantities, and the kerosene lantern became an inexpensive source of high-quality light.

By the time I arrive in Titusville, I am 150 years too late for the boom. But I am here for the historical ambience, not for a job. I check into a hotel that was once a railroad car and still sits on tracks that once carried oil to markets. That oil was burned in lamps, and later in ships, and still later in automobiles.

The tracks run beside Oil Creek, a shallow river with a rocky bed thirty feet across from bank to bank, a gurgling stream of the sort that trout call home. From 1785, seven decades before Drake, in the memoirs of General Benjamin Lincoln: “In the northern parts of Pennsylvania, there is a creek called Oil Creek, which empties itself into the Allegheny river, issuing from a spring, on the top of which floats an oil, similar to what is called Barbados tar, and from which may be collected, by one man, several gallons in a day.”