Heaven: A Prison Diary (30 page)

Read Heaven: A Prison Diary Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous

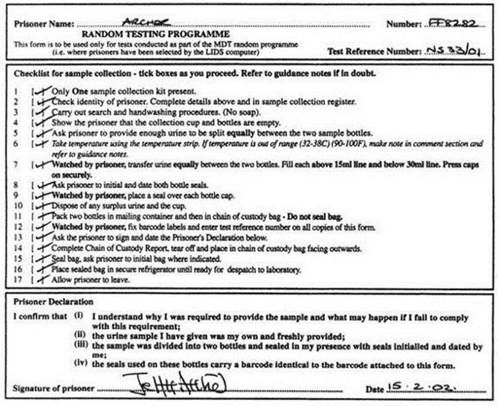

PRISON

SERVICE CHAIN OF CUSTODY

PROCEDURE

Having

completed this procedure, I sign another form to confirm that I am satisfied

with the way the test has been conducted. I am then released to return to the

hospital.

Despite this

being a humiliating experience, it’s one I thoroughly approve of. Although I’ve

never got on with Mr Vessey, he is a professional who cannot hide his contempt

for anyone involved in drugs, especially the dealers.

One of the

inmates up in front of the governor this morning has been charged with illegal

possession of marijuana – but with a difference. When his room was raided they

found him trying to swallow a small plastic packet. They wrestled him to the

ground and extracted the evidence from his mouth. Had he swallowed the

contents, they would not have been able to charge him. The packet was one of

those we supply from the hospital containing six paracetamol pills. This one

had an ounce of marijuana inside, and the inmate ended up with seven days added

to his sentence.

Mr Hocking

appears in the hospital carrying a large attaché case and disappears into

Linda’s office. A few minutes later they both come out and join me on the ward.

The large plastic case is placed on a hospital bed and opened to reveal a drugs

kit: twenty-one square plastic containers embedded in foam rubber show the many

different drugs currently on the market. For the first time I see heroin, crack

cocaine, ecstasy tablets, amphetamines and marijuana in every form.

Linda and Mr

Hocking deliver an introductory talk that they give to any prison officer on

how to recognize the different drugs and the way they can be taken. Mr Berlyn

and his security team are obviously determined that I will be properly briefed

before I am allowed to accompany Mr Le Sage when we visit schools.

It’s

fascinating at my age (sixty-one) to be studying a new subject as if I were a

firstyear undergraduate.

The new

governor, Mr Beaumont, is making a tour of the camp and spends seven minutes in

the hospital – a flying visit. He has heard the hospital is efficiently run by

Linda and Gail, and as long as that continues to be the case, gives them the

impression that he will not be interfering.

8.45 am

Yesterday I was

frog-marched off to do an MDT. Today there’s an announcement over the tannoy

that there are voluntary drugs tests for those with surnames beginning A-E.

These are known

as dip tests, because once again you pee into a plastic beaker, but this time

the officer in charge dips a little stick into the beaker and moments later is

able to give you a result.

I walk across

to the Portakabin, supply another 60ml of urine and I’m immediately cleared,

which makes yesterday’s test somewhat redundant.

I later learn

that one of the

Bs

came up positive, and he had to

call his wife to let her know that he won’t be allowed out on a town visit this

weekend. As it was a voluntary test, I can’t work out why he agreed to be

tested.

Surgery is always

slow at the weekend because the majority of inmates who appear with various

complaints during the week in the hope that they will get off work remain in

bed, while all those who are fit never visit us in the first place.

Carl and an

inmate called Jason who is only with us for two weeks (motoring offence) turn

up at the hospital. Together we remove all the beds from the ward and push them

into the corridor, before giving the hospital a spring clean.

Jason tells me

that ‘on the out’ he’s a painter and decorator, and could repaint the ward

during his two-week incarceration. I shall speak to the governor on Monday,

because at £8.20 a week this would be quite a bargain. You may well ask why

Carl and Jason helped me with the spring clean.

Boredom.

The spring clean killed a morning for all of us.

I watch the

prison football team lose 7 2, and witness two more pieces of unbelievable

stupidity by fellow inmates. Our goalkeeper, who was sent off by the same

referee the last time we played, shouts obscenities at him again, and is

surprised when he’s booked. I fear he will be back in prison within months of

being released. But worse, our centre forward is a prisoner who’s just come out

of the Pilgrim Hospital after a groin injury, and has been told to rest for six

weeks. He will undoubtedly appear at surgery on Monday expecting sympathy. It’s

no wonder the NHS is in such crisis if patients behave so irresponsibly after

being given expert advice.

6.01 am

If I had been given

the same sentence as Jonathan Aitken, I would have been released today.

Jonathan was sentenced to eighteen months, and because he was a model prisoner,

only had to serve seven (half minus two months on tag). Tomorrow I will not be

returning home to my wife and family because Mr Justice Potts sentenced me to

four years.

Instead I will

be meeting Mark Le Sage, an officer from Stocken Prison who visits schools in

Lincolnshire, warning children of the consequences of taking drugs.

I will remain

at NSC until I know the result of my appeal, but for the first time in seven

months (since my mother’s funeral) I will be able to leave the prison and

return to the outside world.

10.00 am

Mr Le Sage does

not turn up for our meeting.

The governor of

HMP Stocken has decided that they should not have to bear the cost of my

accompanying Mr Le Sage on any school visit, as it would no longer be a

voluntary activity that Mr Le Sage would normally pursue in his off-duty time.

As so often is

the case in prisons, someone will look for a reason for

not

doing something rather than trying to make a good idea work. I

cannot pretend that I’ve become so used to this negative attitude that I am not

disappointed. Mr Berlyn is also unable to mask his anger, and seems determined

not to be thwarted by this setback. He has decided that NSC will send its own

officer (Mr Hocking) as my escort, so that I might still attend Mark Le Sage’s

lectures. As I won’t know if this suggestion will be vetoed until Mr Berlyn has

spoken to the Stocken’s governor, I will continue in my role as hospital

orderly.

Alan Purser,

the prison drugs counsellor, comes across to the hospital to give me a copy of

The Management of Drug Misuse in Prisons

by

Dr Celia Grummitt. Dr Grummitt will become my new bedtime companion.

Mr Vessey has

charged Chris (lifer, murder) and David (lifer, murder) with being on the farm

in possession of four potatoes and a cabbage. In normal circumstances this

would have caused little interest, even in our selfcontained world. However,

this will be the new governor’s first adjudication, which we all await with

bated breath.

10.00 am

Mr Beaumont

dismissed the charges against Chris and David as a farm worker came forward to

say he’d given them permission to take the potatoes and the cabbage.

As part of my

preparation for talking to children about the dangers and consequences of

drugs, I have a visit from a police officer attached to the Lincolnshire drug

squad. Her name is Karen Brooks. She’s an attractive, thirty-five-year-old

blonde, and single mother of two. I mention this only to show that she is

normal. Karen has currently served two and a half years of a four-year

assignment attached to the drug squad, having been a member of the force for

the past fourteen years: hardly the TV image of your everyday drug officer.

She gives me a

tutorial lasting just over an hour, and perhaps her most frightening reply to my

endless questions – and she is brutally honest – is that she has asked to be

transferred to other duties as she can no longer take the day-to-day strain of

working with drug addicts.

Karen admits

that although she enjoys her job, she wishes she’d never volunteered for the

drugs unit in the first place, because the mental scars will remain with her

for the rest of her life.

Her son, aged

twelve, is a pupil at one of the most successful schools in Lincolnshire, and

has already been offered drugs by a fourteen-year-old. This is not a deprived

school in the East End of London, but a firstclass school in Lincolnshire.

Karen then

tells a story that brings her almost to tears. She once arrested a

twelveyear-old girl from a middle-class, professional family for shoplifting a

pair of socks from Woolworth’s. The girl’s parents were horrified and assured

Karen it wouldn’t happen again. Two years later the girl was arrested for

stealing from a lingerie shop, and was put on probation. When they next met,

the girl was seventeen, going on forty. Three years of experimentation with

marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy and heroin, and a relationship with a

twenty-year-old drug dealer, had taken their toll. The girl died last month at

the age of eighteen. The dealer is still alive – and still dealing.

As Karen gets

ready to leave, I ask her how many officers are attached to the drug squad.

‘Five,’ she

replies, ‘which means that only about 10 per cent of our time is proactive,

while the other 90 per cent is reactive.’ She says that she’ll visit me again

in two weeks’ time.

6.30 am

Yesterday I

read Celia Grummitt’s pamphlet on the misuse of drugs in prisons and the

following facts bear repeating:

a.

Seven

million people in Britain take drugs on a regular basis (this does not include

alcohol or cigarettes).

b

.

Sixteen million people in Britain

smoke cigarettes.

c.

Drug-related

problems are currently costing the NHS, the police service, the Prison Service,

the social services, the probation service and courts – the country – eighteen

billion

pounds a year.

d.

If Britain did not have a drug

problem, and by that I mean abuse of Class A drugs such as heroin and crack

cocaine, we could close 25 per cent of our jails, and there would be no waiting

lists on the NHS.

e.

In 1975, fewer

than 10,000 people were taking heroin.

Today it’s

220,000, and for those of you who have never had to worry about your children,

just think about your grandchildren.

10.00 am

Mark Le Sage,

the young prison officer from HMP Stocken, visits me at the hospital. He’s been

in the Prison Service for the past twelve years, and for the last eight, has

spent many hours

as a volunteer addressing schools

in

the Norfolk area.

Mr Berlyn joins

us, as it was his idea that I should attend a couple of Mark’s talks before I

venture out on my own. As I have not yet passed my FLED,

I’ll have to be

accompanied by Mr Hocking, who has also agreed to carry out this task in his

own time, as NSC

do

not have the funds to cover the

extra expense (£14 an hour). Mr Berlyn says that he’ll write to the governor of

HMP

Stocken today,

as Mr Le Sage comes under his jurisdiction.

Blossom

(traveller, see page 193) is at the High Court today for his appeal. He’s

currently serving a five-and-a-half-year sentence for stealing cars and

caravans. He’s grown his beard even longer, as he’s hoping that the judge will

think he’s a lot older than he is, and therefore shorten his sentence. He

intends to shave the beard off as soon as he returns this evening.

Blossom returns

from his appeal and announces that a year has been knocked off his sentence. It

had nothing to do with the length of his beard, because he was only in the dock

for a couple of minutes and the judge hardly gave him a second look. He had

clearly read all the relevant papers long before Blossom showed up.