Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (15 page)

That territory now sits on the edges of the self-declared Islamic caliphate, declared in 2014 by a terrorist group famous for its brutality and religious intolerance. It only adds to the awful dilemmas that the Yazidis face, now that their territory is no longer remote from its neighbors. They additionally face the challenge of maintaining a secret religion, whose truths are known only to a priestly caste, at a time when members of the faith live side by side with people of other religions in cities rather than in remote villages—meaning that they are exposed to questions about their religion that they are often not well equipped to answer. For those who have moved abroad, it is likewise not easy to keep children from marrying outside their faith or caste.

Mirza is now confronting those challenges, because he left Iraq long ago—in 1991. The Gulf War had begun, bringing with it the threat of conscription into a doomed army. He joined a group that included a friend of his called Abu Shihab, who was trying to escape with his whole family. They crossed the border that Iraq shares with Syria at a place a short distance west of Sinjar. It was a summer’s evening, and the terrible heat of the daytime was subsiding. Because of the war, the army had been diverted elsewhere; forces on the border between Iraq and Syria were stretched thin. Once inside Syria, the group was going to head for a Yazidi village whose people were friendly—but miles lay in between, and in crossing them they would have to keep an eye out for land mines and for guards who had orders to shoot on sight.

Mirza started walking. He ducked and crept along where he had to. Halfway through the journey he heard gunfire. He thought Abu Shihab, who was trying a parallel crossing a mile away with his wife and all his children, had run into trouble—and so he had. Abu Shihab’s family had been spotted by the border guards. These had shouted warnings and then started shooting. The bullets came close, and one of Abu Shihab’s sons was hit in the neck. But then they were across the border, and nobody came after them. They did not celebrate for long, for they soon realized that the family’s two youngest children were not with them. These two, too small to walk, had been riding on a donkey, and somehow, in the rush across the border, nobody had noticed that the donkey had not kept up. The two children were captured and returned by the government to their grandfather—on the condition that if they escaped, the grandfather’s life would be forfeit. Abu Shihab did not see them again for seventeen years.

Abu Shihab, the rest of his family, and Mirza all migrated to North America—Abu Shihab to the United States, Mirza to Canada. They remained close. Perhaps it was their shared experience at the border that led Abu Shihab to approach Mirza and ask him to be his “brother in the afterlife,” or spiritual mentor. In former generations this relationship was an almost feudal one, involving a layman’s absolute obedience to the sheikh. The relationship is sealed by taking soil from Lalish, rolling it into a ball, which represents the world, and mixing it with water from Lalish’s sacred Kaniya Spi, or “White Spring.” The two spiritual brothers then clasp each other’s hands with the moistened earth in between. This fraternal gesture is not only one that binds Yazidis together. It also is a reminder of a past time when cultures learned and adopted customs from each other. It is the Yazidis’ original contribution to Western life—for this is the custom that, thanks to the cult of Mithras, has become our handshake.

—————

IN 2014 I RETURNED

to northern Iraq after the Yazidis had been driven out of Sinjar by the so-called Islamic State terrorist group. I talked to refugees who had fled their homes, walking 25 miles nonstop to escape the murder, rape, and kidnap that had been inflicted on those who had not been lucky enough to get away. All the Yazidis who packed around me in their tiny shelter, desperate to tell their stories, had one request: they wanted to leave Iraq. “It’s broken,” one of them said. “Our honor is gone, our livestock are gone, our women are gone. We have no future in Iraq.” Their white-robed sheikh, who proudly told me of his descent from the one-time Yazidi ruler of Sinjar, said the same. Surrounded by followers who believe in his power to foretell the future, he predicted the end of his religion in Iraq. In the background, I saw the pointed white spires of a Yazidi temple, reminding me of how long this religion has been practiced, in one form or another, in this ancient and bloodied land. Perhaps no longer.

L

AAL SHAHRVINI WAS BORN IN THE 1920

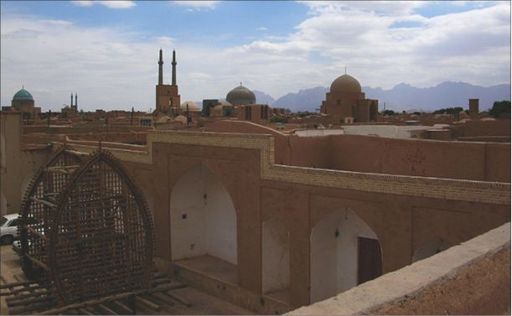

s in the city of Yazd, an oasis in the heart of Iran surrounded by low and barren hills. Today, the whole of Yazd’s old city has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Mud-brick walls frame alleyways and streets down which no car can go. Tall wind towers—shaped like huge chimneys, these are early and picturesque forms of air-conditioning that capture summer breezes and filter them down to the sweltering houses below—loom overhead. Mysterious stairways lead down to cisterns where people once took shelter from the heat, which in summer can reach 114 degrees Fahrenheit. In the main square sits a wicker wheel bigger than a man, a replica of Hussein’s tomb that Muslims carry around the city on their shoulders once a year as an act of penitence.

Laal never went to watch these Islamic passion plays, or to pray at the mosque with its turquoise faience domes and tall minaret. She was not a Muslim: hers was a smaller and older community. Her people had their own festivals and commemorations, such as the winter solstice, when they would stay up through the year’s longest night, bringing watermelons and pomegranates out of storage to eat as they told stories until dawn. The spring solstice, when the day finally became longer than the night, was the most important festival of their year. Purity was central to their lives: to achieve it, Laal went through a ritual requiring nine nights of wakefulness, during which a priest sprinkled bull’s urine over her body and gave her a few drops of it to swallow. She declared that of her own free will, she was joining “the brotherhood and sisterhood of those who do good.”

The old city of Yazd, built from mud brick and dating back many centuries, still partly survives. To the left is the

nakhl,

representing the death of Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Mohammed; it is used in yearly parades. Photo by the author

Instead of despising dogs, as the Muslims of Yazd did, she was tasked by her family with putting out food for them every night, before she and her family could have their own meal. Instead of praying at a mosque, her family offered litanies and burned sandalwood in front of a sacred fire in a nearby temple. Each night her father, a priest, climbed onto the roof of their mud-brick house; she would see him standing there with a sextant and astrolabe, taking measurements of the stars. In the family’s prayers they used Avestan, a language that was last used in everyday speech in the Iron Age. At home they spoke their own language, which others pejoratively called “Gabri”: it was spoken and understood only by those who shared their religion.

Laal’s traditions were practiced by most Iranians before the coming of Islam. When the horsemen of Pars province in the sixth century

BC

rode north, east, and west to conquer their neighbors and build the largest empire that the world had yet seen, which they named Pars or Persia, Laal’s was the religion they followed. It had reached them from central Asia, where it was founded perhaps around 1000

BC

by a prophet named Zarathustra. His followers are called Zoroastrians in the West. Arabs call them Majoos, after their priests, the Magi (also called

mobed

s). In India they are known as Parsees, the name given to them after they arrived as refugees from Persia shortly after the Islamic conquest. Early Christians often depicted the Three Wise Men who were said to have visited Jesus as Persian Zoroastrians: although this is never specified in the account in the Gospel of Matthew itself, it was a lucky choice. When the Persian armies conquered Bethlehem in

AD

614, it is said that they spared the Church of the Nativity from the destruction they visited on the rest of the town, because they saw a depiction of three Magi at the church’s entrance.

Once the dominant religion of Iran, by Laal’s time Zoroastrianism had dwindled: her community, one of the last to survive centuries of mistreatment, numbered only eighty-five families living in the same quarter of the city, a group small enough that Laal knew them all. In all, there are fewer than a hundred thousand Zoroastrians in the world today. But their contribution to world religion, including our own, makes them more important than this figure suggests. According to Nietzsche, Zarathustra invented morality. More certain is that Zarathustra taught that the world was formed by the ceaseless struggle between good and evil. “Between these two,” he declared in his Gathas, poems that form the oldest and most important part of the Zoroastrian scripture, the Avesta, “let the wise choose aright.” The worshipers of false gods had chosen evil, and his followers were to abandon those gods, worship instead the wise lord Ahura Mazda, and do good in his service.

In subsequent centuries this theology developed into an explanation of the world’s imperfections. Why do night, winter, sickness, and vermin exist? Zoroastrians explained them as the work of Angra Mainyu, the Adversary, who sent down evil animals to harm the good ones made by Ahura Mazda. Ahura Mazda created light; Angra Mainyu polluted it by inventing darkness. Ahura Mazda brought life; Angra Mainyu partially spoiled it by introducing sickness. Ahura Mazda represented fertility; Angra Mainyu brought the desert. Ahura Mazda’s kingdom was one of eternal joy; Angra Mainyu’s was one of torment. Although Zoroastrians looked forward to the ultimate victory of good over evil, they had to help make it happen.

The good animals included the horse, the ox, and the dog. Angra Mainyu’s servants in the animal kingdom, called

khrafstra

s, included flies, ants, snakes, toads, and cats. A Zoroastrian Persian emperor called Shapur condemned Christians because they “attribute the origin of snakes and creeping things to a good God.” For him, such things could only be the creation of a separate, malign creator. The great Persian national epic the

Shahnamah

begins with a great army of fairies and animals that had chosen the side of good over evil, setting out for battle with Angra Mainyu. (If this sounds like C. S. Lewis’s

The Chronicles of Narnia,

that is because he was a great admirer of the

Shahnamah

—and he called Zoroastrianism his favorite “pagan” religion.)

The battle between good and evil was one in which human beings could take part if they chose. The concept of free choice is especially important in Zoroastrianism, which holds that even Angra Mainyu is bad by choice. (This is why the story is told that Angra Mainyu created the peacock just to show that if he wished to, he could make beautiful things instead of ugly ones.) Virtuous acts such as telling the truth were means to defeat Angra Mainyu—the forces of darkness in the Avesta are called “the lie”—and the Greek historian Herodotus, who studied the Persians in the fifth century

BC

, tells us that they were brought up to “ride horses, shoot straight, and tell the truth.” But there were also physical battles to undertake against Angra Mainyu’s servants. Herodotus tells us that “the Magians kill with their own hands all creatures except dogs and men, and they even make this a great end to aim at, killing both ants and serpents and all other creeping and flying things.” Even in the 1960s, Iranian Zoroastrians observed a day every year during which they killed

khrafstra

s

,

especially ants.

Loving dogs, meanwhile, was obligatory. In the Avesta, the Chinvat bridge, across which a soul must pass safely if it is to enter paradise, is said to be guarded by two dogs. When a dog stared intently into the middle distance, it was thought to be seeing evil spirits invisible to humans, and so was often chosen to sit by the bedside of a dying person. In turn, when such a dog died it was accorded special funeral rites, as described by the scholar Mary Boyce in her observation of traditional Zoroastrian life in the 1960s. An announcement would be made as the dog died: “The soul is taking the road.” The dog would be dressed like a Zoroastrian—in a girdle called the

kushti

and muslin vest called the

sedreh,

which were always worn by the faithful (the first around the waist and the other over the shoulders)—and its body would be treated like that of a Zoroastrian man or woman who had died: it would be exposed in a deserted spot for the birds to eat. For three days after its death its favorite food would be put out for the dog’s spirit to enjoy.

To maltreat a dog is prohibited by the Avesta. “When passing to the other world,” the soul of a person who has hit a dog “shall fly howling louder and more sorely grieved than the sheep does in the lofty forest when the wolf ranges.” A man who kills a dog is required by the Avesta to perform a list of penances eighteen lines long. One of the penances is to kill ten thousand cats. Because Muslims preferred cats over dogs, which they think of as unclean, disputes over the treatment of dogs often led to fights between Zoroastrians and Muslims.