Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (37 page)

She spent that night in the kitchen, chopping up the body of the dead man and stuffing it into a plastic bag. She told her husband to dump it somewhere in the desert. He chose a bad spot, dropping it in an area that turned out to be an archaeological site. The lights of his car were noticed and guards came to investigate. He escaped, but the bag was found and its ghastly contents uncovered.

The guilty parents knew it wouldn’t be long before they would be identified. The dead man’s family was looking for him, and their own daughter had disappeared; people would soon understand what had transpired. So they fled. The dead man’s family took revenge in the old way. Seven people from the guilty family were murdered before the blood feud was considered settled. And then, said the priest, the guilty couple returned. “And at the wake for one of the people who had died, the mother of the murdered Muslim man turned up. She said to the couple, ‘If you had only told us what you had done, we would have thanked you for killing him. We would have killed him ourselves, if we had known.’” But the insult of leaving his corpse unburied had to be avenged.

Love and death have a long association in Egypt. Near Minya I saw the tomb of Isidora, daughter of a pagan priest under the Ptolemies, who died when she swam across the Nile for a clandestine nighttime meeting with her lover, whom her father had forbidden her to see. The tomb became a pilgrimage site for young lovers. They face even greater obstacles today: love affairs between Christians and Muslims are frequent causes of violence between the two communities. Egyptians are not often left free to choose whom they marry, and under both Islam and Egyptian law marriage is not an equal relationship. Islam does not allow a Christian man to marry a Muslim woman, and in Egyptian law the children of a couple take their father’s faith, not their mother’s. So Christian women who marry Muslim men will be unable to bring up their children as Christian. Most of those who marry Muslims are ostracized by their families; many convert to Islam. A Coptic bishop estimated in 2007 that between five thousand and ten thousand Copts convert to Islam every year, and Coptic priests have separately commented that the large majority of these converts are girls under the age of twenty-five. The fear of losing their daughters to Muslim suitors is yet another reason for Copts to build social networks that do not cross the religious divide.

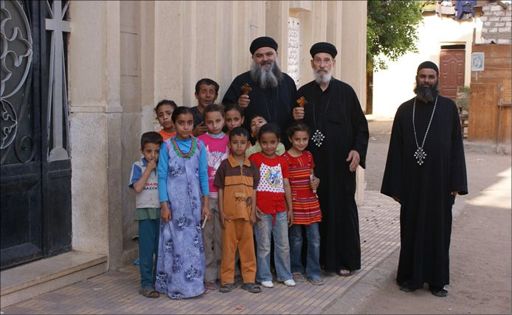

Coptic priests remain significant figures in their communities. By the law of their church, they all must marry. Some of the children here are from priests’ families. Photo by the author

Other conversions have happened because of the Coptic Church’s almost total rejection of divorce: Pope Shenouda tightened the rules until only adultery could be a basis for ending a marriage. Copts who want to leave their husbands or wives for any other reason must first leave the church. Some join another Christian denomination; others become Muslims. Some of this last group try afterward to return to the Coptic Church, but by doing so they risk sparking conflict, for an apostate from Islam must, according to the shari’a, be put to death. In such disputes, religion becomes a way for husbands or wives to rally a wider community to their side. Abeer Fakhry, for example, a Coptic woman living in Minya, fell in love with a Muslim man and left her husband for him in 2011. She was traced by her family and detained by the Coptic Church, which tried to persuade her to return to her husband. It was rumored that she had already converted to Islam, however (a rumor she subsequently confirmed), and so her detention provoked riots and church burnings by Muslim fundamentalists and a gunfight that caused twelve deaths. In Atfih, a suburb of Cairo, a love affair between a Coptic man and a Muslim girl sparked riots in which, again, a church was burned.

External factors could spark conflict, too. A few months earlier, Father Yoannis said, a television station run from Cyprus by a Coptic priest called Zakaria Butros had become famous for its attacks on Islam. At the peak of its infamy in Egypt, Coptic priests had experienced exceptional hostility from local Muslims. A group of Muslim women, for instance, had spat at Yoannis. “People who broadcast hate against Islam, insults to the Koran and who burn Korans,” he said, “this all has very serious, bitter consequences for us.”

—————

I ASKED FATHER YOANNIS

whether Copts ever lived in entirely Coptic villages. It was unusual, he replied, because so few Christians in Egypt practice agriculture. Two villages that he knew of were entirely Coptic, though, and he agreed to take us to one of them, Deir al-Jarnoos. George was a little doubtful. The people in Deir al-Jarnoos, he said, were “toughs.” “Nobody gives them any trouble,” he said. “In fact, all the villages round about are scared of them. When they gather as a group and come out of their village, everybody else runs away.” Father Yoannis knew how to handle them, though. As he drove us in, he rolled down the window and called out endearments to every man, woman, and child he could see: “How are you, honey? How beautiful you look!” He had an effusive style—and perhaps wanted to make sure that people would look at him and see his clerical dress and the cross hanging from the rearview mirror. Cars carrying strangers were not a common sight in this place.

The state had no presence inside the town. In this, Deir al-Jarnoos was a Christian equivalent of militantly Muslim towns of southern Egypt that the police never dare to enter. And just as those towns (and sometimes suburbs of Cairo) can enforce their own rules without much regard for Cairo, so Deir al-Jarnoos was building a huge church that dwarfed the humble houses that crowded around it. On the roof of the church, men in gray

jelaba

s were constructing domes and towers to make it stand even higher on the horizon. We climbed up to meet them, and Father Yoannis asked them where they were from. Asyut, they said, referring to a city another hour or so south. “Ah, Asyut,” he said. “The

best

people are from Asyut.” We climbed back down and inspected the old stone church next door. A villager pulled the wooden lid off a well just inside the church door and lowered a metal cup by a rope into the water below. He invited me to drink. It was a holy well, he said; when Jesus was brought to Egypt as a baby, his family had drunk from it. He hoisted the cup up and I sipped the cool water.

—————

THE FOLLOWING DAY

George came with me when I went to see a whole group of Coptic priests, courtesy of Father Yoannis—who also came. We met in a village not far from Minya, in a house attached to the village church. A black-bearded man named Father Mousa was our host, and a friend of his called Younus sat with us, too. Younus remarked, “The older generation treat Christians like brothers. Most of my friends are Muslims. They come to our festivals, they pray in the church. There is a priest here who exorcises demons; he is very popular with Muslims as well as Christians. But then the Salafis come from the universities. It’s the Salafis and the Muslim Brotherhood who mistreat Christians. They tell Muslims not to greet Christians in the street. And the new generation, those between eighteen and twenty-seven years old, they are a bad generation. They have had very bad teachers. It started with Sadat.” There was a new tradition, he added, according to which Muslim boys would hit Christians on the last day of a school term. “The teachers don’t seem to encourage it,” Younus said, “so far as we can see. Soldiers used to go to the school to stop it, but they couldn’t be everywhere. And after the government fell, there were no rules at all. No fear of soldiers, no fear of guards, no fear of God.”

Education was the problem, Mousa agreed. He had served in the army, three decades earlier or so, alongside a man from northern Egypt. Muslims and Christians mostly go to school together, in state-run schools (there are Christian-run schools that were set up by Western missionaries in the nineteenth century, but they are too expensive for poorer Copts to afford; they cater to upper-middle-class Copts and Muslims). Because Christians had historically lived mostly in the south, this northern man had never met one before. When he saw the cross that Mousa was wearing, he shrank away. “What is this cross?” he asked Mousa, and added, “I was taught that it was a demonic symbol.” In a Pew poll in 2011–12, only 22 percent of Egyptian Muslims said they knew anything about Christian beliefs or practices—the schools’ syllabus does not provide an adequate understanding of religions other than Islam—and 96 percent thought that Christians would go to hell.

Despite their stories, this group of Copts still had great affection for their country. Mousa’s nine-year-old daughter was sitting in a corner of the room, writing on a piece of paper; when I looked at what she had written it was in English, in pens of different colors: “Egypt is my mother. Egypt is my blood. I love you

EGYPT

.” But Copts were leaving Egypt, I said to George as he drove me back to Minya one last time. “Everyone would go if they had the chance,” George said. “Muslims are a bit better off than Christians because they can work in Saudi Arabia. And security is a special problem for Christians, but it’s bad for everyone. I have a good place and a nice job, but I’d give it up tomorrow to go to America and work in a restaurant, if it would provide my son with a good safe future.” Emigration to the West is the Copts’ preferred way out. In the United States there are more than two hundred Coptic churches and an estimated three-quarters of a million Copts.

The next day I took the slow train back to Cairo. There was one more thing for me to do before leaving Egypt. I got on the city’s Metro and returned to the church of St. Thérèse, fourteen years after my last visit. I arrived about halfway through a service. There was Father Paul saying Mass, and two men I knew, Ashraf and Magdi, were acting as deacons—clashing cymbals at the holiest moments, just as their forebears had done for thousands of years. I caught up with the three of them after the service as they walked across to the presbytery. Father Paul had a slight stoop, and Ashraf’s hair was white, but they remembered me. Where was Samih? I asked. He had gone to America, they said; he went to study and ended up staying. What had happened to Maggie? She had married a French man and gone to Paris. Where was Wael? He had followed his dream of becoming a fashion model in Beirut. It was not the Copts who would lose from all this outflow of talent, I thought: it was Egypt.

I went back to the church. A woman in a black Islamic

niqab,

with only her eyes showing, had waited for the Mass to end before coming forward from her seat at the back. She lit one of the thin wax candles that stood in a tray of sand by a pillar, then slowly descended the steps that led down to the crypt chapel. I followed, to say goodbye to the saint whose effigy lay down there. As we stood in front of it, the Muslim woman leaned down and touched St. Thérèse’s side.

I

N SUMMER 2007 I WAS ON A FLIGHT

to Kabul from Islamabad, which had meant several hours of sitting on my bags in Islamabad’s departure terminal. It was easy to tell when foreigners were heading for Kabul: they were mostly burly, muscular characters with North Face backpacks. I was an exception—a very unmuscular diplomat headed for a year’s assignment running the political team at the British embassy. The landscape I saw out the plane’s window looked as if it had been unchanged for centuries. “Mountains brown like snuff,” one British traveler had called them, “ten-thousand-foot mounds with the track snaking its way through for mile on heavy mile.” Looking closely, I could spot thin green threads between the hills, which were the valleys. Human habitation was not visible at all.

Gazing eastward, I saw high peaks rising sheer above the green valleys and the brown mountains, up to a height of twenty-four thousand feet. These were the Hindu Kush, a great mountain range that runs along the eastern borders of Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan and separates those countries from China. They are really part of the Himalayas. Though they are called the “Roof of the World,” it is more apt to think of them as a wall or a rampart: many times over, they have been the furthest point eastward that any people has reached. These mountains are to human cultures what coral reefs are to marine life: rich and diverse. In the Afghan section of the Hindu Kush, for example, in an area the size of New Jersey twenty indigenous and mutually unintelligible languages are spoken.

Alexander the Great reached these mountains but made no effort to cross them—thinking, perhaps, that they formed the very easternmost edge of the world. Their inhabitants taunted him, undaunted by the fact that he was the conqueror of Persia and ruler of the greatest empire the world had yet seen: to capture their inaccessible hideaways, they said, he would need “soldiers with wings.” In one of these battles, Alexander was wounded in the shoulder by an arrow. The great commander had never lost a battle in the eight years since he had left his homeland in northern Greece. But these opponents, one of Alexander’s chroniclers recorded, were the toughest fighters that he encountered in his entire Indian campaign. Alexander was so impressed that he married a local girl, Roxane (“the loveliest woman they had seen in Asia,” his soldiers thought, with the exception only of the Persian empress).