Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (9 page)

—————

IN THE 1940

s

there were still over a hundred thousand Jews in Iraq. In 2003, when I visited Baghdad for the first time, I saw what little remained of them. In a quiet road in an old quarter of Baghdad a dusty house sat empty; when I knocked at the door, a curtain opposite twitched. This was Baghdad’s Jewish community center. It had been abandoned in rather a hurry, from the look of it. In an upstairs room I found Hebrew-language schoolbooks heaped on the floor. A ledger sat next to them, wedged between old typewriters. The latest entry was dated December 21, 1969. What happened to Iraq’s ancient Jewish community, so that by 2003 nothing remained but a pile of dusty schoolbooks? I asked this question of Moshe and Yvonne Khadhouri in a comfortable flat in London. Back in 1940, when Iraq was still a monarchy, Moshe and Yvonne were both living in Baghdad. As they remembered it, it was a Jewish-friendly city. “On Saturday, the banks in Baghdad were closed for the Sabbath,” Yvonne said, “because all the banks but one were Jewish-owned. The textile trade was all Jewish. We were a third of the inhabitants of Baghdad.” Both of them lived through the ghastly events of June 1941 when the monarchy was briefly overthrown and, for three days, a mob whipped up by Nazi-sponsored anti-Semitic propaganda attacked the city’s Jews. It was called the

farhud

.

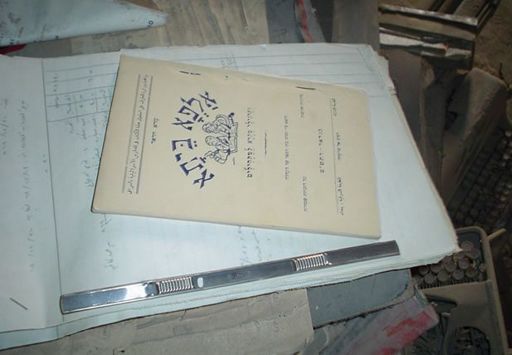

A Hebrew schoolbook and dusty typewriters are almost all that remained in 2003 of Baghdad’s Jews, who once made up as much as a third of the city’s population. Photo by the author

“The Muslims are not bad people,” said Moshe. “The Nazis came to Baghdad. And Israel made a lot of trouble between Jews and Muslims. If not for politics—”

“It was religion that was the problem,” interrupted Yvonne. “And there were only a few that were nice people.”

They both agreed, though, that more than seven hundred Jews were killed during the

farhud

. And although things then returned to normal, with British troops entering the city to forcibly restore the monarchy, the situation deteriorated after the foundation of Israel in 1948 and the final collapse of the monarchy in 1958. In the years that followed, many Jews were denounced, and some were hanged—nine of them in January 1969, a few months before the community center was abandoned. Many were sacked from government jobs and saw their property expropriated. Moshe stayed till the 1960s and Yvonne till the early 1970s. He missed Iraq more than she did. “My daughter wants to look for roots,” he said. “There are no roots anymore. The cemeteries were razed. All my heritage is there, but our communities are lost. I want to feel patriotic. Not in Israel. Not in England. I am Iraqi. I feel I’ve been robbed.”

Until 2003, the Mandaeans escaped the fate of the Jews. In the following ten years, however, their fortunes would change, and Nadia would hear from a Jewish Iraqi exile a glum verdict comparing the two communities’ fates with the sequence of their different sabbath days: “We were on Saturday, and you are on a Sunday. Now your Sunday has come.”

—————

BAGHDAD IN EARLY

2003 was a place simmering with suspicion and fear. From time to time demonstrators (paid, everyone knew, by the government) would parade through the streets, shouting their support for Saddam. Once a crowd of excited men thought they had seen an American soldier hiding in the thick reeds that lined the Tigris, which runs through the city, and beat the reeds with heavy sticks as they tried to hunt the intruder down. Nadia was not interested in campaigning for or against Saddam. She only wanted to keep her brother safe. He had just received call-up papers from the Iraqi army; he was to join the force that would resist the American-led invasion. If he obeyed the draft, she feared, he might be killed. If he did not, he risked a brutal punishment: the amputation of an ear. And so, in their family’s small house in southern Baghdad, the two of them argued over whether he should enlist. She thought not. She was the older sibling and had no interest in conforming to traditional ideas of feminine meekness. If she was going to persuade him, she knew, she had to be more intimidating than Saddam. “If you ignore those papers, I’ll pay every bribe you need,” she said. “And if you obey the call-up, then I’ll break your arm.” He relented.

Nadia told me that she had almost never encountered discrimination from Muslim Iraqis. At school she had met one pupil who declined to eat her food and called her

nejas,

an Islamic word meaning “unclean.” But otherwise she felt that, if anything, being a Mandaean meant that she was treated with extra respect. (This was in a middle-class part of Baghdad; in rural areas, things might have been different. In Suq al-Shuyukh even now, there are eating places and coffeehouses that refuse to serve Mandaeans because they are believed to pollute the utensils they eat with.)

Educational standards dropped during the era of sanctions, as Nadia had described to me, and Iraqi society became coarser—but it was only after the US-led invasion in 2003 that she began to sense danger. She was drawn into arguments at work. “Saddam was like a crown on our head and the invaders are

kuffar

,” said one colleague—

kuffar

being the plural of

kafir

, a word that legitimizes violence against nonbelievers.

“I think he was like a pair of slippers. You put him on your head if you want to!” Nadia replied.

As time went on, she found it harder to sustain her bravado. The conflict gave plenty of opportunities for religious bigotry to fester. “We started to hear of people being kidnapped, hijacked, killed just like that,” Nadia told me. Her own workplace, the Red Cross, was bombed in October 2003. The violence struck even closer to home four months later. On January 18, 2004, she was on her way to assist at an international charity in Baghdad when she heard an explosion. Not only heard, but felt—the car she was in shook with the force of the blast. “The sky was cloudy,” she remembers, “and I got a strange feeling afterward, as if someone I knew had been caught in the explosion. So I called Hadeel.” Nadia and Hadeel, a Christian woman, knew each other from working together in a print shop in Baghdad in the 1990s. In 2003 Hadeel had taken a job with the American embassy and had also managed to find her ideal husband—an Iraqi dentist working in Denmark. Nadia and her other friends had bought her an engagement ring, which Hadeel wore on the same finger as the ring given her by her fiancé.

“I called Hadeel’s house; her little brother said she had gone to work. I called her mobile phone, and the mobile phone of a friend who used to go to work with her. No answer. I called her colleague, and he said she had never arrived. When I went home I called her family. They said she had just disappeared. Hadeel’s mother called me later—she knew I worked for the Red Cross—and she said, ‘I want you to get good news about my daughter.’” News came, but it was not good. The car Hadeel had been in turned out to have had a bomb planted under the driver’s seat. It was detonated, and killed the driver; two other women in the car had been injured. But there was no news of Hadeel. Nadia took a day off work and toured the hospitals looking for her. She found nothing. It was only later that she heard. The body had been hard to identify, the hospital said. It was badly burned. The only things that remained uncharred were two rings on one of its fingers.

Hadeel’s family went ahead with the wedding party anyway and sang the traditional celebratory chants and ululations. But they did it after having buried the bride. “And they said, ‘This is not the wedding we wanted.’ I couldn’t bear seeing them again. It was such a pointless waste of life. I think people should be aware of these stories before they go to war.” The death preyed on Nadia’s mind and made her want to leave. “I thought, I don’t want to be killed like my friend. I don’t want to break my parents’ heart.”

Nadia had never defined herself by her religion. “I see myself first as a human being, second as an Iraqi, and only third as a Mandaean,” she told me. But humanism and patriotism did not help her in postwar Iraq, where more atavistic loyalties came to the fore. Religion was not the only thing that put her in danger: so did her ability to speak English, and the facts that she did not wear a veil or belong to a tribe. “I realized the power of the tribes,” she said. “And we, as Mandaeans, don’t have a tribe.” In the past Mandaeans had used the time-honored tactic of attaching themselves to a tribe not as members but as dependents, an “annex.” The tribe would agree to protect them, but since they remained outside the tribe proper, they did not have to accept its religion. In the frightful horrors of Iraq after 2003, Nadia’s family had a tribe to protect them, but, as she said, “they don’t provide as much protection to their annexes as to their own people.” Mandaeans were exposed to kidnapping, forced conversion, and murder. Between 2003 and 2011, the Mandaean Human Rights Group documented 175 murders and 271 kidnappings. In 2004, the group reported, thirty-five Mandaean families living in Fallujah were forced to convert to Islam.

Nadia got on a plane leaving Baghdad on March 18, 2004. Her identity papers—she had no passport and had never been on a plane before—were stamped for the first time. Her parents were worried for her: if she lived abroad on her own, no man would marry her afterward, they fretted. She found London so expensive that she had to pawn her jewelry to pay the rent, and she was startled by the “much milder culture.” She missed Iraq and nostalgically sought out the fragrance of orange blossoms. Going with her friends to Iraqi concerts, she was quizzed by Iraqi Jews who had left Baghdad forty years earlier and wanted to hear the latest news about their favorite places there.

Despite the nostalgia, she abandoned thoughts of returning home. “I love it there,” she said, “but I can’t live it.” She was not the last Mandaean to leave. Two years after her departure the high priest Sheikh Sattar fled to Australia. By the time of this writing, more than 90 percent of the Mandaean population of Iraq has emigrated or been killed. It is only in southern Iran that one can find their communities intact. Nadia believed that the Mandaeans’ departure was a loss for Iraq. “We were the fulcrum in a pair of scales—holding Iraqi society together. And when the Mandaeans and other minorities left, the scales were broken.” And after what we had both seen from looking back in the Mandaeans’ history, Nadia and I could agree: with their departure, Babylon has truly fallen.

O

N A STREET IN A CITY IN CANADA

, looking up at an apartment block any day at dawn, one may see a window lit: Mirza Ismail is praying, as he also does at noon and sunset. No outsider may witness his prayers, and since no other member of his own community lives nearby, he performs them alone. Each time he prepares himself carefully. He washes his hands and face and winds a special girdle called a

pishtik

around the white shirt he always wears. Then he prostrates himself toward the sun and begins praying in Kurmanji, the language of his people, to an unknowable God. “There is no god but God,” the prayer declares, “and the sun is the light of God.” He prays that God may give the world peace.

Mirza is a soft-spoken Iraqi man with a neatly trimmed salt-and-pepper mustache, and because he prays at regular intervals during the day, colleagues and acquaintances often wrongly assume he is Muslim. He is instead a Yazidi, a follower of an esoteric religion that has superficial similarities to Islam but is very different from it. Although his people are often thought of as Kurds and speak the same language (Kurmanji) as their Kurdish neighbors, he insists that they are a separate people. Sometimes called Ezidis, they number hundreds of thousands in northern Iraq and in parts of Syria, Georgia, Armenia, and northwestern Iran. Yazidis believe in reincarnation, sacrifice bulls, and revere an angel who takes the form of a peacock. Their traditions forbid them to eat lettuce or wear blue; men must grow a mustache, though few have beards. They are also victims of an ancient calumny—the accusation that they worship the devil. And even before 2014, they were the victims of the second-deadliest terrorist attack in history.