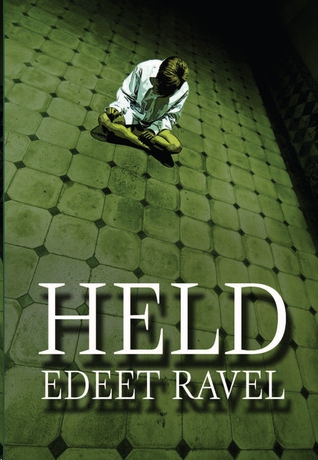

Held

Authors: Edeet Ravel

HELD

EDEET RAVEL

for John

Contents

Washington, D.C.

Monday, 4:00 a.m.

You’ve asked me to tell you everything. You’ve brought me to the best hotel in Washington, D. C., you’ve given me the hotel’s best suite. There are flowers in every room, gift baskets on every table. There’s a fireplace in the living room, heated tiles around the Jacuzzi, a fully equipped exercise room. I can order any meal I want, any time I want it. I imagine movie stars staying in these rooms, or famous world leaders.

I’m not alone. There’s an armed guard outside my suite, a bodyguard on the terrace. Twice a day a nurse arrives to take my blood pressure, and every afternoon a psychologist named Monica comes to visit. My mom joins me for meals and usually spends the night in the guest bedroom, though she has her own suite one floor down.

You’ve told me the guards are there to protect me and that I’m free to do as I please. I’m not a prisoner. I can see anyone, go anywhere. I need only pick up the phone and make my desires known. But you suggested, courteously, that I remain indoors for a few days—it’s safer for me, you said, and of course I understand that it’s simpler for you. You reminded me that people from the media have infiltrated the hotel and are waiting for an opportunity to pounce on me, and that the crowds outside are barely manageable.

The laptop you’ve given me sits on the polished dining room table. My instructions are to write a detailed account of my experiences. When I’m finished, you’ll let me go home.

I notice that you’ve emptied the bar. I assume you would have emptied it even if I’d been old enough to drink. You don’t want anything to distract me from my task.

Looking down from the terrace, I can see the crowds on the street holding signs and banners and enormous posters with my face printed on them. “

I love you, Chloe

,” the signs say. The bodyguard tells me that entire families have come to Washington to welcome me home; they’ve flocked in from every part of the country.

How can they love me? They don’t know me.

I can also see the media people, wandering aimlessly between the camera stands, bored and impatient. They want me, but I’m not giving myself to them. Not yet.

Mom hopes that in a few days we’ll be able to fly home. She’s been giving interviews and press conferences, and she tells me about the people she’s met, the requests we’ve had from TV celebrities, publishers, and magazines, the wild sums of money I’m being offered for my story. She describes the small army of journalists who follow her everywhere, bombarding her with urgent questions.

We don’t discuss what happened to me. Not because she’s afraid to ask, but because she knows I’m not ready to talk about it. Or maybe what I’m not ready for is sorting out what I do and don’t want her to know.

Thousands of gifts keep pouring in. The gifts are delivered to Mom’s suite: clothes, luxury getaways, every sort of pretty object. She’s keeping as many as she can manage for me and my friends; the rest are being redirected to charity. On my first day here she brought me a whole pile of outfits from the best boutiques, but I haven’t tried any of them on yet. I’m still wearing the track pants and T-shirt they gave me at the clinic. Room service takes them away at bedtime, and when I wake up they’re on the marble table in the outer foyer, cleaned and neatly folded.

But this isn’t a vacation. You’ve brought me to this hotel for a reason: you need information. You told me to write down everything that happened to me from the day I was taken hostage to the day of my release. I have to record every detail of the past four months, no matter how small. You showed me magazines with cover stories about me; you told me the entire country was devastated by my ordeal.

After lunch the psychologist drops in. We talk about the weather, about what I’ll do when I get home, about getting back to school and catching up on what I’ve missed. I’ve spoken to Angie once, and to my grandparents. I haven’t gone on Facebook, I haven’t contacted anyone else. I told everyone I was tired.

But the real reason is that I’m not entirely ready to return to my old life.

I’m sitting on the king-sized bed now, writing on the hotel’s gold-and-blue stationery. What I’m writing will not be seen by you, will not be read by you. Even if you’ve installed a camera in these rooms, you won’t be able to see my small, abbreviated handwriting, which I’m shielding with my body.

On the laptop you gave me, I’ll produce another report, the one you will see. It will be factual, concise, accurate. It will not be complete.

But here, on pale-blue, gold-engraved paper, I will write the real story. The one you’ll never read.

I was taken hostage in Greece on the third of August.

I was working at a summer volunteer program with my friend Angie, just outside Athens.

My friend Angie—

I look at those words, and they seem to belong to someone else. It’s as if I were a ghost, drifting through a world I’ve left behind and can never reclaim.

A volunteer program abroad was my idea, but Angie and I decided on Greece together, mostly because the photos on the websites we checked out were so beautiful—white domes, gold sand, every shade of blue. Angie, who loves to paint, said the colors would inspire her, and I remembered the Greek myths my father used to read to me; I still had the books, and I’d browsed through them often over the years. Athena, Apollo, Aphrodite. Labyrinths, adventures, transformations.

Mom was also enthusiastic about Greece; she’s a dance teacher and choreographer, and in her twenties she traveled to Europe and the Far East to learn about indigenous dances. Greece was her favorite stop, and it was one of the reasons she’d named me Chloe—after a ballet,

Daphnis and Chloe

, based on a Greek story.

We landed in Athens at the beginning of June. The volunteer supervisor picked us up at the airport and drove us to one of the city’s suburbs, where we’d be teaching kids at a community center. The

katikies

, as our rooms were called, were pretty dismal, and we soon found out that we’d also be expected to wash dishes, mop floors, and take out garbage.

But the cute kids and the amazing surroundings more than made up for any disappointments. I taught dance and gymnastics to a class of well-behaved, enthusiastic girls, and Angie worked in the arts and crafts room. On our free days we joined excursions organized by the center. We explored islands, wandered down narrow streets with vine-covered houses, went scuba-diving, and stuffed ourselves with Mediterranean food. We watched the sun set in Oia; we watched the sun rise behind the Parthenon.

Our favorite fellow volunteers were Camille and Peter, tall blond twins from Norway who loved to joke and laugh. We bonded on the first day, when Camille’s suitcase was accidentally shipped to Japan and we told her to help herself to whatever we had. Angie developed an instant, hopeless crush on Peter, who unfortunately for her already had a girlfriend back home.

A crush was nothing new for Angie, who’s always falling madly and usually hopelessly in love. Not that guys don’t like her—on the contrary, she has a great personality and she’s gorgeous; her Argentinean mother used to be a model and Angie inherited her charisma.

But she tends to fall for unattainable types—ski instructors who are engaged, university students who consider her a kid (her father teaches at Northwestern and every semester he has a party for his grad students), or some guy she’s seen in a dance competition on TV and decided she has to meet, even if he lives on some distant ranch in Canada.

Angie’s disappointment that Peter had a girlfriend was alleviated by the constant attention that came our way from the local male population, who had never heard of the word

shy

, in Greek or in English. Angie enjoyed flirting back, which only made them bolder.

In my book, they were stalkers, but Angie said I needed to be more open-minded to “mating customs in other cultures,” a phrase that made all four of us—especially Camille—laugh hysterically. “Your friend does not like us,” the guys would say to Angie in my presence. “Why is it?”

But it wasn’t true that I didn’t like them. They were simply too random for me; I couldn’t trust some stranger, no matter how good-looking, who appeared out of nowhere. Camille said I wasn’t at ease with guys because I’d grown up without a father or brother, but Angie insisted that my problem was an obsession with control and order. I had to be in charge, she said. I had to plan and organize everything, including who I met.

Classes ended on the first of August. We were sorry to be leaving the community center, and so were the children. They gave us little presents and asked us to stay in Greece forever.

Our return flight was three days away. We were allowed to stay in our

katikies

and explore on our own, as long as we were back before dark. We asked Camille and Peter to join us, but they were meeting friends in Italy. We hugged one another good-bye and they made us promise to visit them in Norway.

On our first free day Angie suggested we head out without a plan and let things unfold. We’d get on a bus, see where it took us, have an adventure.

I resisted. “We have to at least know where we’re going,” I said.

It’s always been like that: we’re almost identical in every other way, but when it comes to being organized we’re opposites. Angie’s room is like a big jumble sale, and every few days she’d call and beg me to come over and help her find something crucial that she’d lost. I’d be like one of those professionals who tidy houses—I’d spend two hours folding her clothes, putting papers into neat piles, arranging all her paints and pastels. A week later, the room would be back to its usual post-tornado state.

It was the same with going out places. Angie was laid-back, but I liked to know where we were headed, how long everything would take, and what we had to bring with us.

Especially now that we were in a foreign country and didn’t even speak the language.

But Angie was very persuasive. She said she’d had enough of schedules and rushing around. She wanted to relax. Reluctantly, I agreed to get on a bus and see what happened.

The day was jinxed. We got lost in a sketchy town in the middle of nowhere, Angie’s sandal strap broke, a scary old man began to follow us, we were hot, we couldn’t find water, and we had a terrible meal at a dumpy restaurant that left us feeling sick.