Hell-Bent (35 page)

Authors: Benjamin Lorr

Instead, a senior teacher interjects, saying, “So it seems like what you are saying is the Olympics are no longer the goal.” Bikram grunts at this. The room remains silent. Then Bikram continues speaking, rambling

forward on an entirely different issue. The discussion is over. Now it is just Bikram talking and an audience to listen to him speak.

I wonder what would happen if I stood up and said something about any one of his totally false claims. I wonder how the room would react. But instead, I make eye contact with a Backbender across the room. She makes eyes back at me and then rolls them deep in the back of her head. I nod toward the door. She shakes her head no. As if to say, I know this is silly, but I want to stay. I smile back. But I have had enough of Bikram for one life, and so I close my notebook and walk out.

Later, and as a fitting coda, I find one of the judges from the competition. She is a woman who has taken the entire process perfectly seriously—embraced Rajashree’s idea of an open, fair competition; a gymnastics for yoga; a meeting ground of different lineages and styles.

“I couldn’t take another moment. It was madness in there. Everything being changed just as it is decided … And yesterday was worse! Nobody ever told me to change my score exactly, but they also made sure we got the message.” The woman is not angry, but very focused. Staring off like she is working through an important calculation. “We were gathered in a group and instructed. It was all very clear. You know, stuff like, ‘You’re an idiot if you scored her more than a zero,’ things like that.”

I listen and tell her that sounds very tough and a little sad. I say I hope someday Bikram Yoga can grow into something beyond Bikram’s Yoga.

She looks at me a moment. “Sad? I just wish they would make it clear, so we knew exactly what to do.”

Making It Clear

And then, two months after internationals, Esak is out.

With the ineluctable logic of narcissism, the true disciple—who did everything right, who submitted and fetched Coca-Cola after Coca-Cola, who massaged and preached and built an entire life for himself that was incased within Bikram, within the community, and within the yoga—is out.

Bikram banishes him. His exile is announced with a quick note on the official website:

To My Dear Studio Owners,

It is with much sadness I share this message that Esak Garcia has left his wife, his son, me, and the Bikram Yoga Community. As he has joined another weird organization and is with another woman. This is reason why nobody can invite him to do any kind of seminars, lectures or anything whatsoever in a Bikram Yoga school or in our family.

Thank you,

Bikram.

38

It is a note whose paternalism and clumsy attempts at sincerity indicate all the contempt they are trying to hide. Esak didn’t want to leave the Bikram Yoga community. It was a community he helped build, that he gave himself into, that he expected to sustain him when he needed a web of support, and that provided a substantial income. When I spoke to him a few days after reading the note, he told me it felt “completely surreal.”

He was indeed separating from his wife, something he had discussed with Bikram in confidence. But he in no way wanted to leave the Bikram community.

“There isn’t too much for me to say at this point. I can’t help but feel there has been a huge misunderstanding.”

It is a misunderstanding only in the sense that it was always a misunderstanding. That this is exactly how it has to end. Exactly how it has always ended.

The banishment came just days before the latest incarnation of

Backbending—now officially and resolutely named Jedi Fight Club—was set to start in Lawrence, Kansas. This was the first clinic where Esak was going to charge a flat fee instead of accept donations. No more scrounging for meals at midnight. No more vague and unpredictable schedule. He had hired a vegan chef to prepare restorative meals after the day’s practice. He had retained a masseur for endless hours of professional-quality bodywork, and he had arranged a Mary Jarvis seminar to kick off the two weeks. It was going to be the best Backbending/Jedi Fight Club ever.

But Bikram was getting left behind. The exact reasons are lost between Bikram and Esak. Maybe Esak was unwilling to put up a high-enough tithe. Maybe Bikram, like Emmy, thought repetitive extreme backbending was unsafe and poorly represented his yoga. Maybe he was sick of seeing Esak’s purple Jedi Fight Club shirts at every one of his events. Maybe he realized that Esak, the one man who never told an aspirational lie, who never made an excuse for anybody including himself, simply had too much integrity. Or maybe Esak just got complimented one too many times in his presence. But for whatever reason, Bikram decided Esak had outlived his usefulness to him, he decided the best, most responsible way to handle this was public banishment, and suddenly Esak—who had months of seminars scheduled in advance, whose career, life, son, and mother were rooted in the yoga—was left to try to levitate when the rug was pulled out from under him.

The community was shocked.

“I just don’t understand.”

“Terrible misunderstanding.”

“Best not to talk about it until we know all about the details.”

“Just something that makes me very confused and very sad.”

But there was one man who wasn’t confused at all. Jimmy Barkan, Bikram’s head of instruction for the late ’80s and early ’90s. A man who devoted himself to Bikram with almost the same passion as Esak.

“Of course,” he says with a laugh. “The only reason I got to become a senior teacher was all my predecessors had a falling out. … Bikram is very threatened by any career uprising. … And if I’m going to be completely

honest, it was only when I moved across the country that I became really close to Bikram.

“If you do exactly what he tells you, you’ll get along fine for a while,” Barkan says. “That was the key to my relationship with him. And—relatively speaking—I lasted a long time. I was extremely deferential. I was there to learn.”

But eventually, even the three thousand miles of space separating Barkan’s South Florida studio and Bikram couldn’t stop the inevitable.

“He kept cutting me down every time my career would take off. I started running a yoga retreat in Costa Rica, and then he told me to stop going because Emmy didn’t like the place. Then I got a book deal—fitness yoga for golfers, with the potential for sequels planned for other sports—but Bikram forbid me from continuing with the project. The publishers were completely baffled.

“Then, I was teaching private lessons to Dan Marino and the Dolphins, and got a chance to make a video with them—NFL players doing yoga in the early ’90s way ahead of its time—an amazing opportunity. But Bikram put a stop to it. He forbid me from doing the video. … Finally he made demands that would have financially ruined me. I was opening a second studio in Florida with his permission. Six months after opening, Bikram decided he didn’t approve of the layout and ordered me to close. … It was impossible. So I didn’t do it. I didn’t bow down. And so I was out.”

Just like Esak.

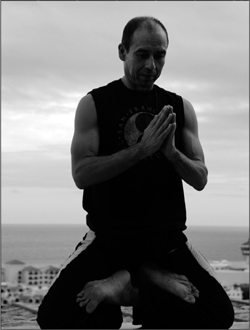

Tony Sanchez in Montain Posture

Patricide: Patricide is a bad idea, first because it is contrary to law and custom and secondly because it proves, beyond a doubt, that the father’s every fluted accusation against you was correct: You are a thoroughly bad individual, a patricide!—member of a class of persons universally ill-regarded. It is all right to feel this hot emotion, but not act upon it. And it is not necessary. It is not necessary to slay your father, time will slay him, that is a virtual certainty. Your true task lies elsewhere.

—DONALD BARTHELME,

THE DEAD FATHER

Everything is an evolution. To believe that yoga is different is an incredible act of denial. We must improvise, we must modify, and if that doesn’t work, we must be willing to throw the system out. … If you want to learn yoga, spend some time asking yourself why. Then do yourself a favor and take a cooking class. That will definitely improve your life.

—TONY SANCHEZ

The Wise Old Man on the Mountain

In almost every Bikram studio, there is a poster of an elegant dark-skinned man completing every Bikram posture to absolute perfection. Many assume it is Bikram himself as a youth. It turns out the man is a Mexican-American named Tony Sanchez, who studied with Bikram from the age of eighteen onward, living with the guru as family. When Bikram traveled to India to meet his bride-to-be, Rajashree, Tony accompanied him as best man. Bikram called him “my greatest creation.” He asked Tony to demonstrate endlessly. He put photographs of Tony on the walls of his guru’s school in Calcutta. But ultimately, as with all his creations, Bikram grew threatened. And so, on Tony’s birthday in 1984, Bikram had his accountant

drive him over to the studio Tony managed to have a talk. For the occasion, Bikram choose his most impressive car at the time, a Daimler limo, complete with toilet and wet bar.

At the studio, as everyone else made preparations for a birthday celebration, Bikram asked Tony to step aside for a conversation. Among other things,

he demanded Tony break up with

his girlfriend—soon-to-be wife—Sandy. When Tony said no, Bikram fired him.

The last thing he said to Tony, greatest creation and best American friend, was “No hard feelings.”

Their separation grew outwardly hostile a few years later when Tony decided to produce a line of yoga videos. The videos featured a series he created using the ninety-one postures Bishnu Ghosh compiled. They were not the series that Bikram taught, and they included postures that Bikram could not begin to do. “I called Bikram to tell him about the videos. My business partner, the guy who put up all the money, thought we should try to get his blessing.” Tony explains, “When I called, there was no discussion. He ordered me to stop. He started yelling hysterically. He told me if I proceeded with the videos, I would ‘die soon.’” Tony laughs. “I told him, ‘Guess I better get on with it then, before I die.’”

Tony’s name comes up at Teacher Training exactly twice. Both times feel achingly sad.

The first time, Bikram is sidetracked during a lecture, talking about the early days. A student asks him about his marriage to Rajashree, how they met. Bikram responds with his typical mixture of irreverence and dismissive charm. “Oh, that. Same old story. Arranged marriage. Took seven minutes. Fly to India. Fly back. Nothing special.”

39

The room laughs, and Bikram moves on to talk about the party his students threw for him when he returned. Quincy Jones and L-Like-Linda had organized a reception. Linda raised forty thousand dollars from students in two weeks. Quincy provided

the house. Bikram gets lost in the memories from that period. He talks about the students he loved; he talks about how he helped each one of them open a studio of their own, each in different cities. Then he starts listing names.

In the middle of the memories, mid-name, he stalls out. “Ton—You know, that Chicano guy, whatever his name was …”

An older teacher in the audience shouts out helpfully, “Tony Sanchez!”

Bikram ignores her. He repeats, “Whatever his name was …” Then his voice trails off. He shakes his head, there is a tiny silence, and the memories are over and the lecture moves on.

The second time, Bikram is not in the room. Neither am I. I hear about it later from a senior teacher. Rajashree is talking about her yoga practice as a youth. She talks about her demonstrations, her concentration competing. She explains a difficult stunt she performed as a child, where she would dangle her stomach over a sharp knife while her guru broke a brick over her back. “I really don’t know how it was done,” she says. “You know, he wouldn’t let me do it all the time, so I think it must have actually been dangerous.” Then she talks about an injury she got, early in her time in America, when she pushed herself too far in a backbend during a demonstration. A teacher asks why she doesn’t demonstrate anymore.

Rajashree pauses and considers the question. She seems pleased with the notion and laughs: “I think the only way I’d demonstrate again is if Tony was up there with me.”

After his exile, Tony opened a nonprofit yoga studio in San Francisco. It grew quite successful, classes packed and Tony charging three hundred dollars per hour for the private instruction he squeezed in between. Tony rooted his instruction in the yoga Bikram taught him, although instead of relying on the Beginning series, he incorporated all of Bishnu Ghosh’s ninety-one postures. There was no heat. When Bikram students would come and ask about it, he’d tell them, “You mastered the heat, now let’s try mastering the cold.”

He was regularly featured in

Yoga Journal.

A program he designed to bring yoga in the classroom won the first prize from the San Francisco Education

Fund for Most Creative Learning Environment. Soon he crossed into the mainstream with articles in the

New York Times

, BBC, and

Los Angeles Times

. When scholar Gudrun Bühnemann wrote her book

Eighty-four Asanas,

examining historical representations of hatha yoga sequences, she sought Tony out because he was the only modern practitioner she could find at the time who practiced a complete eighty-four-asana sequence, and could demonstrate it in full.