Here Comes the Night (19 page)

The session ran way overtime. The single was the last track of the night. Spector made everybody do take after take. He went out in the studio and practically dictated how he wanted the drum fill to go with drummer Gary Chester. Pitney lost his voice and was forced to retreat to his falsetto to reach the final notes. The $500 budget ballooned to more than $14,000. But Schroeder knew, after all that, Spector had bottled some high-voltage electricity. At the end of the session, he tried to slip Spector a $50 bill, but Phil wouldn’t take it.

Spector got what he wanted at Aldon. Even Nevins and Kirshner stepped aside for the hot kid and gave him the song he wanted, “I Love How You Love Me.” Spector brought the Mann-Kolber song back to the West Coast, where he had recorded the Paris Sisters earlier in the year for Lester Sill’s Gregmark label and done surprisingly well. Spector spent grueling hours in the studio working on the follow-up, painstakingly crafting a self-conscious masterpiece.

He slowed the ¾ time of the song down to a funeral dirge and rehearsed the vocal parts endlessly around a piano in the studio, carefully polishing the echo on lead vocalist Priscilla Paris (whom Spector was seeing on the side). He obsessively worried about the string sound and went back into the studio many times to remix. When he was done, Spector had created an eerie evocation of his old Teddy Bears hit. The record made the Top Five when it was released in September, by which time songwriter Barry Mann was already writing with a new partner.

Cynthia Weil, one of the few of the young songwriters not from an outer borough, actually raised in Manhattan, fell for Barry Mann pretty much as soon as she laid eyes on him at an audition in the offices of producer Teddy Randazzo. She had started out at Broadway composer Frank Loesser’s office but had most recently been working out of Hill & Range. She spent time around Aldon, waiting for Mann to notice her.

They started to date and they started to write. Kirshner heard her sing on one of Mann’s demos and hired her. Mann’s “Who Put the

Bomp,” a nutty, semiautobiographical send-up he wrote with Gerry Goffin, hit the charts in September. Orlando finally recorded the follow-up to “Halfway to Paradise,” the first song to be recorded by the new songwriting team of Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, “Bless You,” which made number sixteen in October. They were married before it slipped down the charts.

Spector went back to Hill & Range. He quit his job at Atlantic Records in April, the day his nightclubbing pal Ahmet Ertegun married his new wife, the estimable Mica Banu Grecianu. (Ertegun had courted his bride, an ex-wife of Romanian aristocracy, by, among other things, hiding a small orchestra in her bathroom at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel to play “Puttin’ On the Ritz.”)

Spector also had severed his association with Leiber and Stoller. Copies of Spector’s contract had mysteriously disappeared from the files at Leiber and Stoller’s office (“Jerry,” asked Stoller on one memorable phone call, “did you give Phil Spector keys to the office?”). Leiber and Stoller had successfully blocked Spector from landing songwriting assignments for an upcoming Elvis movie he had been finagling at Hill & Range, but Spector was still working out of the publishing company’s offices.

Through Hill & Range, he found three acts—the Ducanes, the Creations, and the Crystals. He farmed out his offhand productions of the out-of-style white vocal groups—the Creations to Philadelphia’s Jamie Records, and the Ducanes to a grateful George Goldner for his Goldisc label. Spector kept the Crystals, although Hill & Range was under the impression he was rehearsing the girl group in their offices for their Big Top label. But secretly, Spector had gone into partnership with Lester Sill to start their own label, Philles Records (a contraction of their first names). He brought arranger Jack Nitzsche out from Hollywood for the sessions. The single “There’s No Other (Like My Baby)” was the breakout record on New York radio and retail of the first week in November.

While Berns was still waiting for his first big break, his neighbors at Aldon Music in 1650 Broadway suddenly ruled the pop music world. Bobby Vee put out Goffin and King’s “Take Good Care of My Baby” in August. It was their second number one hit. Pitney’s “Every Breath I Take” was released the following week—the same week as Bert Berns’s first hit, “A Little Bit of Soap” by the Jarmels. Sedaka and Greenfield, together and with other cowriters, were still writing Connie Francis hits—“Where the Boys Are” and “Breakin’ In a Brand New Broken Heart” were the latest—and Sedaka’s own singles of his songs still scored. By the end of the year, Aldon Music counted more than ten smash hits on the books. More than a hundred of the firm’s songs had been recorded that year, reported

Billboard

. Even old-timers at the Brill Building couldn’t fail to notice the upstarts.

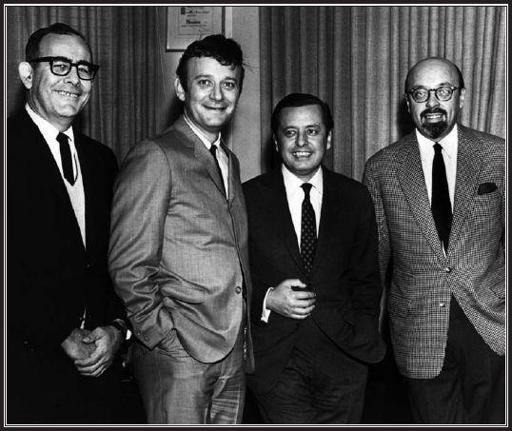

Wexler, Berns, Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun

W

HEN ATLANTIC LOST

Ray Charles and Bobby Darin in 1960, those two artists alone accounted for a third of the label’s sales. Ahmet always depended on his personal relations in business. Charm was his con. He thought his friendship with Ray Charles would hold sway. He knew Sam Clark and Larry Newton of ABC-Paramount. They were squares, grimy merchants without a speck of cool. They were exactly the kind of crass, low-class record men Ahmet especially despised. They weren’t even characters. But they offered Ray Charles an unprecedented deal that would result in his owning his own masters after five years, which Atlantic chose not to match. Clark and Newton needed Ray Charles.

The company had started only five years earlier, a phonograph record wing of the entertainment corporation that produced movies and television. Clark had been a Boston-based record distributor and he brought onboard Newton, a veteran of independent record labels, who guided the label toward the hit parade with fluff like “A Rose and a Baby Ruth” by George Hamilton IV and “Diana” by Paul Anka. But the label desperately needed a cornerstone act like Ray Charles.

Ertegun, still waiting for Ray Charles to call him back for a second offer, read about the ABC-Paramount signing in the trades. He and Wexler were furious and disconsolate. They felt betrayed, bested by slimeballs. They thought—perhaps not unreasonably—they gave Ray

Charles the kind of creative freedom and artistic support he could never have found at any other label and saw his signing with ABC-Paramount as a heinous defection, a personal insult. Charles thought it was business.

Ertegun also invested a lot of time in Darin. He personally delivered Darin’s first real royalty check to him backstage at the Copa. Ertegun thought the $80,000 check represented a substantial sum. Darin’s manager Steve Blauner, whom the Atlantic guys called “Steve Blunder,” looked at the check. “Is that all?” he said.

Ertegun even managed to keep Darin on the charts with trifles such as “Multiplication” and “Things.” Darin’s naked, fearless ambition had always been a palpable part of his appeal and he was living the life of a Hollywood star in his mansion with his starlet wife. When Frank Sinatra called and asked Blauner to meet with the president of his new label, Reprise Records, Blauner used the invitation as leverage to cut a favorable deal with Capitol Records, the label Sinatra had only recently abandoned. Blauner knew his client would never get proper attention at a label owned by Sinatra, and signing with Capitol would allow Darin to record in those same studios and have his records released on the same label as Sinatra. Atlantic had never even been in the running. Darin and Blauner had big-time show business plans that didn’t include some small independent r&b company. Again Ertegun was crushed and Wexler was furious.

Atlantic quickly fell on hard times. Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun, raised in luxury, knew nothing of deprivation. They lived like pashas at a clambake. Ahmet drove his Bentley to Harlem. But Wexler grew up poor. He wanted to make his fortune. He worried about money. He bought the big house in Great Neck, but he was not set. He pushed for the sale of the company’s music publishing firm, Progressive Music, which contained copyrights such as “What’d I Say” and “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.” Freddy Bienstock at Hill & Range snapped up Progressive for a cool half million.

Wexler exiling Leiber and Stoller over chump change was an act of hubris the company could ill afford. They were making hit records over at United Artists. Wexler knew better than to pull them off the Drifters, but even their records weren’t doing what they did. After the number one hit of “Save the Last Dance for Me” in October 1960, the company hit a dry patch. The next Top Ten hit on Atlantic, “Gee Whiz,” came as a surprise to Wexler, who didn’t even know it was his record.

“Gee Whiz” by Carla Thomas was released on a small Memphis label, run by a brother and sister, Jim Stewart, bank teller by day, and Estelle Axton, who also kept a day job while she operated a small record store in a black neighborhood that gave the label its name, Satellite Records. Wexler picked up a previous release by the little label that had stirred some local action, “Cause I Love You” by Carla & Rufus—a father-daughter duo featuring Memphis disc jockey Rufus Thomas and his high school senior daughter, Carla.

It took Wexler one phone call and a thousand bucks, and he promptly forgot about the deal. But when Hy Weiss of Old Town Records, working his day job for Jerry Blaine’s Cosnat Distributors, heard the Satellite pressing of “Gee Whiz” and contacted Jim Stewart about leasing the master himself, he looked over the papers and called Wexler. The deal Wexler made for the initial master turned out to include options on future releases.

After “Gee Whiz” in March 1961, Atlantic was frozen out of the Top Ten for eight months. Ahmet and Wexler no longer worked together in the studio. Neither of them spent much time recording. Ertegun, freshly married to the elegant socialite Mica, bought a bus, so he could take entire parties on his nightly rounds of Manhattan nightlife, starting every night at El Morocco. It was the time of the twist and Ertegun soon discovered the Peppermint Lounge on Forty-Fifth Street, between Broadway and Eighth Avenue, where the house band was Joey Dee and the Starliters and the owners were wiseguys. Mike Stoller ran into the handsome Mafia don Sonny Franzese there one night. Franzese,

cold-blooded enough to shoot a man in the face at a Jackson Heights bar and calmly return to his drink, liked music business types. He took Stoller out to Third Avenue where Franzese and the boys operated a few more exotic clubs and they watched a lesbian love act. Ertegun tried to sign Joey Dee, but before he could, the act landed on Roulette. Morris Levy had the inside track. Ahmet was less interested in making records anyway these days.

Wexler wasn’t doing much more in the studio. The little Memphis label, Satellite, now distributed by Atlantic, also came up with another lucky hit for the company, the instrumental “Last Night” by the Mar-Keys. He spent long hours working disc jockeys and distributors over the phone and using his contacts to find masters from other regional labels like Satellite. He was buying other people’s records, but he wasn’t making them himself anymore. Atlantic’s fortunes were at an all-time low.

SOLOMON BURKE’S BIRTH

was foretold. He came to his grandmother in a dream twelve years before. In anticipation, she founded Solomon’s Temple: The House of God for All People in Philadelphia, and when Solomon finally was born, there was considerable excitement. He gave his first sermon at age seven. By nine, he was known as the Boy-Wonder Preacher. At twelve, he began weekly radio sermons and went out on the road on weekends, taking his ministry into the world.

When he was eighteen, Solomon spent a week writing a song as a Christmas present for his grandmother, who was sick in bed. The day after he finished, she told him she wanted him to see his Christmas present early and, under her bed, he found a guitar. He sang her the song he had written, “Christmas Presents from Heaven.” She spent the rest of the day telling him how his life was going to be. She told him about the loves he would have, big houses, fancy cars. She told him his spiritual message would reach millions, but that he would descend to the pits of hell before he would emerge victorious. The next morning, a week before Christmas, his grandmother died in her sleep.

Shortly after her death, there was a talent contest at Liberty Baptist Church, but Solomon couldn’t convince his group, the Gospel Cavaliers, to enter. One fellow had just bought a TV and another had tickets to the football game. So Solomon borrowed pants and a too-short coat from his uncle, went down and entered the contest by himself. The wife of a local deejay liked what she heard enough to introduce young Solomon to Bess Berman, the tough old dame who ran the New York–based independent label Apollo Records, where Mahalia Jackson made her name. Burke cut a number of inspirational-style records for the label that did quite well. But when Burke raised questions about getting properly paid, his manager warned him he would never record for anyone again and he dropped out of the music world entirely. It was his first descent into hell.