Here Comes the Night (44 page)

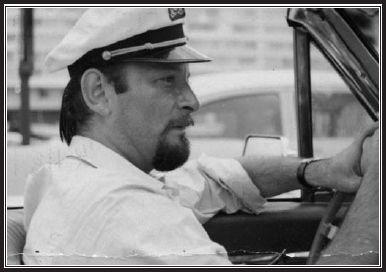

Bert Berns

H

ER PIECE OF

Neil Diamond was all Ellie Greenwich had left. She lost her husband to another woman, and her father figures Leiber and Stoller had abandoned her when they sold her songwriting contract to United Artists. Barry and Greenwich were done writing songs together, except for one last curtain call.

After several years of not working with them after “Chapel of Love,” Phil Spector phoned Barry about writing together again. He either didn’t know that they had split or didn’t care, but Spector flew to New York to work with them. They met at Barry’s West Seventy-Second Street apartment. Greenwich felt weird just being there. There was no real collaboration; everyone came with little pieces of melodies and lyrics that they just assembled like parts. The first, “River Deep—Mountain High,” Greenwich had the verse melody and Spector brought the chorus, while Barry supplied most of the lyrics. They ended up writing three songs in a week, including “I Can Hear Music,” all little suites as much as songs, different chunks of music pushed up against each other.

After the enormous success of “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” the Righteous Brothers and Spector went their separate ways. Spector was looking for a bigger, even more grand sound. He leased for $20,000 the recording contract from Loma Records of Ike and Tina Turner, r&b

stalwarts since their string of hits in the early sixties with Juggy Murray, and spent an astronomical $22,000 on the Hollywood recording sessions that produced the extravagant, titanic “River Deep—Mountain High.”

During sessions concentrating on her lead vocal, Tina ended up stripped to her bra, belting out the song over and over for Spector, a perfectionist known to spend hours working over the same eight bars of music in the studio. When the record was released in May 1966 on his Philles label, Spector watched in agony as his greatest achievement, his most fabulous production ever, creeped and crawled in four weeks up to a pathetic number eighty-eight on the charts before dropping off entirely into oblivion. Spector was devastated. He sat in solitude behind the electronic fences of his Beverly Hills mansion and cried bitter tears.

Ellie Greenwich spent many evenings crying her own tears with Bert and Ilene Berns, whom she found warmly sympathetic. Ilene, young colt that she was, made several awkward attempts to get Jeff and Ellie back together, but stopped trying once Barry went public with his new girlfriend. Greenwich desperately needed the Neil Diamond project. She felt as though, without it, she would disappear.

Berns was definitely a full member of the creative team. He not only attended all the meetings, but also went to the sessions, although he left Barry and Greenwich more than capably in charge. He sang loudly in the background choruses and added handclaps. Berns would also return the next day to work with engineer Brooks Arthur fine-tuning the mixes.

Diamond, still wet clay, absorbed a lot from Jeff Barry, particularly in vocal mannerisms and phrasing. They were both a couple of Brooklyn cowboys who wanted to be Elvis. There was a natural understanding between the two, and Greenwich, after the divorce, felt increasingly cut out.

Don Kirshner loved “Cherry, Cherry” and called Diamond to see if he had anything suitable for the Monkees, the new hit TV series rock

group controlled by Columbia–Screen Gems. The group’s first single streaked to the top of the charts in September 1966. Kirshner loved one new Diamond song, “I’m a Believer,” and offered to buy the copyright, along with a couple of others. Barry could produce the record and Diamond would retain his writer’s share. The two partners in Tallyrand decided to take the songs out of the company and sell them to Kirshner without consulting Greenwich. They never asked her and they neglected to pay her. To Greenwich, it was the sign of her utter hopelessness, her total lack of power. She was hurt and despondent; all this meant more than dollars to her. This was her life.

She poured her heart out to Berns over dinner at La Brasserie, one of Berns’s favored upper Broadway restaurants. She felt comfortable with Berns. She saw him as a boyish man, vulnerable and open, encouraging to be around. Berns’s pet phrase—“I hear what you’re saying”—applied equally to conversation or musical performances in the studio. He wanted people to know he was listening. Greenwich loved that about Berns. She didn’t really expect his reaction.

Berns called Wassel and made him come to the restaurant. Greenwich repeated her story. Wassel asked how much money she was owed and assured her he intended no one any harm. Within days, Wassel collected the money.

But Greenwich could only be so close to Berns and ultimately started to drift away because his friendship with her ex-husband continued to flourish. Shooting pool, riding motorcycles, just bullshitting around, Berns and Barry got along like songs in the same key, but they could not collaborate musically. Ilene Berns watched in amusement as the two emerged from a writing session at the Englewood Cliffs place, each complaining about the other—“He’s too pop,” “He’s too blues.” They managed to eke out a couple of pieces together, and in Berns’s world, no songs went unrecorded. Berns recorded their song “Ride Ride Baby” with a genuine rock and roll phenomenon he signed to Bang Records, Jack Ely.

As a teenager in Portland, Oregon, Ely had been a founding member of a high school rock and roll combo they named the Kingsmen. In one of the great harmonic convergences of rock and roll history, the Kingsmen entered a Portland recording studio the day after another Portland rock and roll band, Paul Revere and the Raiders, went into the same studio, and both recorded the same song—a cover of the Richard Berry original from the Los Angeles r&b scene in the fifties, “Louie Louie.” Ely, who sang the song for the Kingsmen on the record, was fired shortly after the record’s release by a bandmate who secretly trademarked the band’s name and decided he wanted to be the lead singer.

That would have been that if disc jockey Arnie “Woo Woo” Ginsburg hadn’t discovered the record for the “Worst Record of the Week” feature on his popular WMEX Boston radio show. Ginsburg ignited a firestorm of airplay that led Marvin Schlachter of Scepter Records to buy the master and release the record nationwide on Wand.

The Kingsmen—without Ely—sprang back to action and took off on a nationwide tour of television appearances and concert performances. Ely quickly formed his own outfit, Jack Ely and the Kingsmen, advertising himself as “The Original Singer of ‘Louie Louie’.” This was a blood feud, touched off when security guards barred Ely from entering the nightclub where the Kingsmen were recording the band’s album,

The Kingsmen in Person, Featuring “Louie Louie.”

Lawsuits flew.

The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” (with Ely on vocals) went all the way to number two in December 1963, one of the last great blasts of American rock and roll before the Beatles swamped the charts.

“Louie Louie” would not go away. Word spread that Ely’s incomprehensible vocals disguised dirty lyrics, a rumor so persistent, the FBI spent more than two years analyzing the record and investigating the song’s background. The furor even brought the Kingsmen single back on the charts for a couple of weeks in May 1966.

Berns, never shy of the obvious, first cut Ely on Bang singing “Louie Louie ’66” and, for the B-side of the next single, a cover no less

of the Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Louie Louie” follow-up, “Louie Go Home.” Ely didn’t mind. He was a man on a mission. He wanted redemption and retribution. As part of the lawsuit settlement, he was forced to change the name of his band; the Bang singles were done by Jack Ely and the Courtmen.

“Ride Ride Baby,” the A-side of the second single, did capture the joint sensibilities of Barry and Berns, a raucous rock and roll record riding on a riff redolent of “Louie Louie” with an erotic blues underbelly and Neil Diamond somewhere buried in the background chorus. Ely wasn’t around Bang much, but he was there long enough to walk in on a screaming match over royalties between Berns and the parents of the McCoys, a group whose fortunes dimmed rather rapidly after the instant number one success of “Hang On Sloopy.”

After the diminishing returns were not reversed by the group’s snappy sixth single, Feldman, Gottehrer, and Goldstein’s hip, funny, psychedelic bromide, “Don’t Worry Mother, Your Son’s Heart Is Pure,” that ends with a clearly audible toke, Berns took the McCoys into the studio himself with Barry for another savory collaboration, “I Got to Go Back,” the credit reading

PRODUCED BY BERNS AND BARRY

. Again, the song is Barry-brand pop plus sex with a Southern soul rinse, a vibrant, thumping distillation of their two distinct styles, a record far more strapping and appealing than its relatively anemic January 1967 chart performance might imply.

At Roulette Records, Morris Levy was back from the brink of insolvency after a stroke of lightning. Levy never made the records at Roulette. Records were only part of his racket. He made more off publishing. He still owned Birdland, still New York’s premiere jazz club. He had other, less evident ways of making money.

Levy had fingers in many pies. At Roulette, he had to depend on other people’s taste and abilities, which he would then subject to his own endless second-guessing. Teddy Reig hustled Latin records for him, the only thing keeping the label going for a while. Levy brought

back Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore to handle artists and repertoire in 1964.

They had started Roulette off with hit after hit out of the blocks in 1957 and left a year later to run recording at giant RCA Victor for six years. Before they came back, Henry Glover, Lucky Millinder’s old arranger and recording director for years at Cincinnati’s King Records, had made r&b–flavored hits at Roulette with Joey Dee and the Starliters and others. His 1963 record with the Essex, “Easier Said Than Done,” went number one.

Back at the label the next year, Hugo and Luigi found Roulette in sad shape. The big names on the jazz line were all gone. Levy was difficult. He would refuse to pay debts just for the hell of it. He was impossible to pin down about business matters. Hugo and Luigi couldn’t deal with Roulette the second time around and split after less than a year, the label teetering on collapse. When Levy bought the Paramount Theater in 1964, the whole thing started to go down the drain.

Accountants were preparing the company for bankruptcy and the label was down to its last $10,000, when promotion man Red Schwartz ran across a record he thought could do something, “Leader of the Laundromat” by the Detergents, a group of New York studio brats making fun of the big Shangri-Las hit. Since the label would lose the money in bankruptcy anyway, Schwartz picked up the master and humped the dumb record into the Top Twenty.

Although it was hardly thriving, Roulette was back in business. The label had not managed another chart single since and showed a lot of debt with their distributors, who were always reluctant to pay the independent labels, especially if the line wasn’t selling. Often how much you got paid depended on how good your next record was. Roulette was headed back in the toilet when Red Schwartz struck gold in Pittsburgh.

His distributor in Pittsburgh called Schwartz to tell him about a record that was a smash locally on a small label. He thought Schwartz could have it. Schwartz went to Pittsburgh and couldn’t believe his

ears—biggest piece of shit he’d heard in years, but a piece of shit that had already sold forty thousand pieces in the market and was number one and number three respectively on the yokel radio stations. He gave the group’s manager $10,000 and agreed to buy two full-page trade magazine advertisements with his name at the top—

BOB MACK PRESENTS TOMMY JAMES AND THE SHONDELLS

.

Tommy James came from Niles, Michigan, where his band, the Shondells, had been one of a number of teen groups to record for a local disc jockey in 1964. The band covered the Barry-Greenwich song from the B-side of one of the Raindrops singles, “Hanky Panky.” The disc jockey played the record on the Niles radio station WNIL for a couple of weeks and nothing more happened, until a year later, when a Pittsburgh deejay stumbled across the local record and started slamming it on his show as an exclusive.

James, at first, didn’t believe the Pittsburgh disc jockey when he finally reached the teenager by phone, but James eventually made his way to Pittsburgh, where his old, forgotten record was already a hit. He signed with manager Bob Mack and put together a new set of Shondells.

Schwartz had no faith in the group, but he already collected more than $8,000 for the records sold in Pittsburgh. When Levy listened to the record and expressed roughly the same opinion that Schwartz held when he first heard it, Schwartz was able to calm down Levy by telling him it cost only $1,500. “Hanky Panky” went all the way to number one, one of the biggest records of the year. Levy was now truly back in the game.

Levy long provided certain services to the record business. He was the person to call if there might be problems that couldn’t be solved any other way. If an artist’s manager was being difficult and needed to be handled confidentially, Levy could help. He also had a pipeline for selling cut-rate albums, fast bucks for unsold inventory, cash transactions kept off the books. He had been the music industry’s dirty little secret since he was pulling Alan Freed’s strings. Wexler had made his deals with the devil before. He hated to have to do it—Wexler

personally couldn’t stand Levy—but there had been times when there was no suitable alternative.