Here Comes Trouble (16 page)

Read Here Comes Trouble Online

Authors: Michael Moore

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Philosophy, #Biography, #Politics

How Frank came to find himself on Hill 250 on the island of New Britain made about as much sense to him as the fact that his own side was now trying to kill him with such ease. To begin with, no one ever explained to him how these hills got their names; it wasn’t as if there were 249 other hills he had to climb to get to Hill 250. In fact, to even call them “hills” seemed like some War Department cartographer’s idea of a joke. Maybe by calling them hills they would make an American Marine feel more like he was home—and that if he were going to die for this

hill,

then, well, at least he’d feel like he was dying for… home. Home had hills. Hills with trees and wildflowers with names like Yellow Lady Slippers and Jack in the Pulpit and Shooting Stars. Hills with pleasant hiking paths. Hills to hide out in. Hills to pick berries from. Hills where hobos could find a peaceful night’s rest. Hills where you and yours could find a small, quiet space to build a quick fire and make love beside it.

What led Frank to this particular hill was a worldwide war that had nothing in particular to do with

his

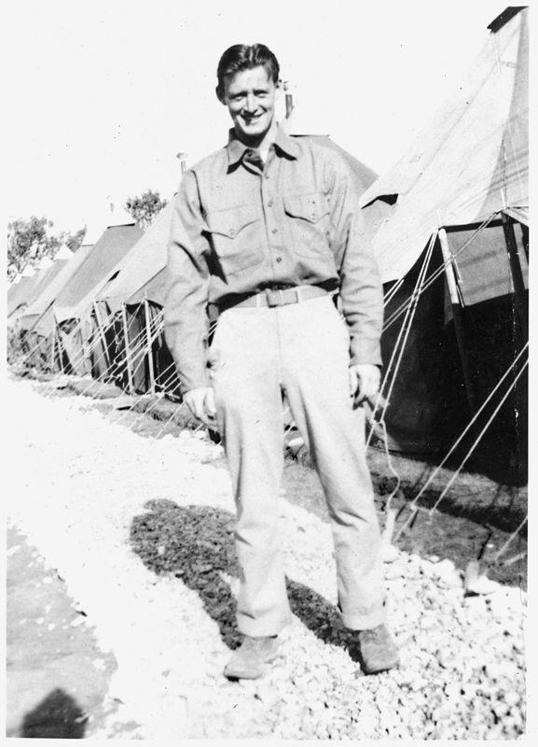

world. His world was one of hard work and sports and Saturday nights at the Knickerbocker Dance Hall. Though they lived the shared poverty of many in the worst days of the Depression, the Moore brothers—Bill, Frank, Lornie, and Herbie—each took extra care to always have a clean, well-pressed suit, a sharp haircut, and enough coin in their pockets to buy a pretty girl the first drink, if not the second.

They took dance lessons upon leaving high school, somehow figuring out that the fairer gender liked to go dancing. Because the other young men in town were slightly less adept at picking up on this, the Moore boys were always the first ones out on the dance floor, and this impressed the ladies. If nothing else, it showed the girls that they were fearless, and that in and of itself was quite attractive. Lornie, sixteen months younger than Frank, became known as the king of the dance floor and soon found himself teaching dance in a downtown dance studio. It dawned on him that he was in fact helping out the enemy by teaching other men how to dance a cool jitterbug, but Lornie had a gentle soul and a generous spirit, and he was just happy to see more people dancing the night away.

Things had been looking up in Flint by 1941. The Roosevelt policies of putting everyone back to work, plus the beginning of industrial production in anticipation of American involvement in a war that had started two years earlier in Europe and the Far East, was enough to prevent a factory town like Flint, Michigan, from collapsing entirely. Bill and Frank and Lornie all had WPA jobs right out of high school (a fact they tried to hide when speaking to girls). By the summer of ’41 Frank had already held down numerous jobs from hawking flyers for a local grocery store to driving an egg truck to (briefly) driving a truck full of the maximum-size (6 oz.), green-tinted Coke bottles. Each of the boys eventually landed the coveted General Motors assembly-line job. Frank, not looking forward to the monotony and repetition of placing the same nodule on an AC Spark Plug 4,800 times a day, took a night class to learn how to type, hoping to get a clerk’s job in the factory’s office. But he couldn’t type as fast as the girls, so he was relegated to Plant 7, line 2, spark plug pin insertion.

Eventually his three brothers saw a bigger world in their future and quit the factory (“Sales, Frank—that’s where the money is!”), and their combined incomes in 1941 were enough to pay the rent on their mother’s home and cease the constant upheaval of being two steps ahead of the landlord and his good friend, the county sheriff.

And after the rent and the food and the coal bills were paid, there was enough left over for the bus ride to the Knickerbocker. Or, if it was a special weekend, to the Industrial Mutual Association auditorium where the likes of Tommy Dorsey and Frank Sinatra would play as they passed through the Midwest. It was, for young working men, a version—a

version

—of paradise.

So it came with some disappointment that the Emperor decided to interfere with their lives on the morning of December 7, 1941. The attack, the elimination of nearly the entire Pacific fleet, came as a shock to the nation. The following day, even as President Roosevelt issued his call to arms, young men flocked to recruitment centers like the one in Flint, Michigan, which had been hastily set up in a large grade school on the near east side of town. The Brothers Moore, though, would not be among those signing up that day, or the next day, or the next week or the following month, or the month or two or three or six after that. It wasn’t that they weren’t upset at Hirohito or any less patriotic or any less eager to go kick some Axis ass. After all, they weren’t known at St. Mary’s High as “dancers.” They were Irish, and they never shied away from a fight.

It’s just that this new war was, well, poorly timed. Bill had just gotten married, and Frank was sweet on a girl who had been the valedictorian of her class at Flint Northern. She planned to go to Ann Arbor, to the University of Michigan, to study medicine, which in those days meant she would become a nurse. Frank had some ambition for further education, but the recent union victories at GM meant that he was making good money, and Ann Arbor might as well have been on the moon. Nonetheless, the valedictorian seemed worth pursuing, so this war was unwelcome at best.

Frank’s father had served in the Marines in World War I, and his uncle Tom had been a doughboy in the trenches in France during that same war. Having been gassed by the Germans, Tom was of ill health and thus lived with Frank and the family in Flint. Frank got to see up close the effect that nasty war had on these two good men. Neither could explain to Frank why America had gone to war in 1917, and so when the drums began to beat again, Frank wanted to know exactly what this one was all about. Yes, it was enough that the nation was attacked—but was there something else we should know? Anything? Something? OK, well, those bastards destroying our fleet was certainly good enough for Frank. He was ready to go fight.

He waited until the last minute, until the draft notices started to arrive in July 1942. He decided he didn’t want to be drafted into the Army—“every man’s for himself in that operation,” he would say—and so on the first of August, 1942, Frank went down to the recruitment center at the large grade school and signed up to be a Marine. A Marine? “The Marines fight as a team,” he told his friends. “They look out for each other.” But his brothers (all of whom would soon enlist themselves: Bill in the Air Force, Herbie in the Navy, and Lornie in the paratroopers, where he would die from a sniper’s bullet in the last months of the war) told him, “Marines are sent into the worst of situations. You’ll get killed in the Marines.”

“Perhaps,” said Frank, “but the Marines never leave a man behind.” After thirteen years of crushing Depression, Frank had had enough of being left behind.

The enlistment officer asked him when he could get his affairs in order to ship out.

“What’s the last possible date I have?” Frank asked.

“August 31,” the recruiter replied.

“I’ll take that day.”

Frank spent that final month enjoying the life he had: working, going to Knickerbocker’s, helping his mother. On the day he packed his duffel bag, he left quietly and went down to the bus station by himself. When he arrived he found himself waiting on a bench with fifteen other Marine recruits. A photographer from the

Flint Journal

snapped a picture of them and captioned it “READY!” The look on Frank’s face in the photograph was anything but READY! and apparently this wasn’t noticed by the copy editor, who let the ironic caption go through and be printed on the page the next day. By that time, Frank was on a train, on his way to basic training outside San Diego, California.

The delay in enlisting not only had bought Frank a few extra months of peace, it caused him to miss the first large Marine amphibious landing in the war—on the island of Guadalcanal. Over 7,000 Marines and soldiers would be killed, along with 29 ships sunk and an amazing 615 planes lost. Frank would not arrive in the South Pacific until the end of the Guadalcanal campaign, and thus he avoided one of the worst massacres of the war. But there would be plenty of other opportunities to die in the next three years.

“Private Moore,” the sergeant whispered. “Cap’n wants ya.”

It was sometime around 11:00 p.m. on Christmas Eve, 1943. Frank Moore wasn’t sure if it was Christmas Eve or Christmas Day, and he didn’t care much for this thing called the International Date Line that meant he was always a day ahead of his life, the life he left back home. Instead of trying to do the math, he just decided to keep himself on “Flint time.” Easier. Friendlier.

He and a thousand other Marines had bunked down early on this night on the transport ship as it headed toward the battle on New Britain, an island that was part of Papua New Guinea, a few hundred miles off the coast of Australia. There wasn’t much Christmas celebrating going on, though there were, no doubt, many, many prayers being said. Because at 0700 hours they would be loaded into amphibious assault vehicles and lowered into the Pacific Ocean just a mile off the coast of Cape Gloucester, New Britain. But for now, Captain Moyer wanted to see Frank.

“I hear you can type,” Moyer said to the young private.

“Yes, sir, sorta,” replied Frank, not quite understanding what typing had to do with killing Japanese or Christmas.

“I want you to stay behind here on the ship,” Moyer said. “I need someone who can type up the casualty reports.”

“But sir…”

“Listen, this is important. We need to be accurate and we need to be accountable. If not to HQ, at least to the families of these men.”

This was, Frank realized, a free Get-Out-of-Dying card being offered to him. Stay behind on the boat. Don’t die in the wave of bullets and mortars that will spray across the chests and the necks and the heads of his friends and fellow Marines. Live for another day. But there were no guarantees of living in the days or weeks ahead.

He had figured out in the previous months of fighting on New Guinea that the South Pacific theater was a slaughterhouse. He wondered: If he had joined the Army instead of the Marines, would he be somewhere in the Mediterranean right now? He figured there was no way that Italians and Germans were fighting tooth-and-nail like these Japanese. Sure, the enemy in Europe wanted to win, but not at the expense of everyone in their unit dying. After all, what’s the point of winning if you’re all dead? He would like to ask a Japanese soldier that question, but never really got the chance as none of them were into being captured, or worse, surrendering.

The offer from Captain Moyer seemed mighty tempting, but Frank knew that staying behind on the ship was only delaying the inevitable. If your time is up, you might as well go on Christ’s birthday.

“Captain, I’d rather stay with my battalion. If it’s OK with you, sir, let me stay with my buddies.”

Moyer had been impressed with Private Moore and how he had volunteered to help the chaplain during Mass, serving as his “altar boy.” Though Moyer was Episcopalian, he often attended the close-enough-to-count Catholic services and observed how reverently Moore treated the whole ceremony, even if it was being said on the stump of a fallen coconut tree. He thought he’d give Moore a chance to live another day, but the kid wasn’t biting.

“OK,” he told the private, “you’re dismissed. Get some sleep.”

“Thank you, sir.” Frank returned to his bunk and for the first time in a long time had no problem falling asleep.

At 0500 hours the booming sounds of the artillery guns from the nearby American destroyers made Frank stop and wonder if he had made a mistake turning the captain down. Someone mentioned that Moyer and a reconnaissance party had slipped down into the bay two hours earlier with the intent of landing before the invasion, under cover of darkness, in order to find out just what the First Marine Division was about to face.

Tucked tightly into his amphibious lander with thirty or so other Marines, Frank said one final prayer before the door came down and deposited everyone into the slosh of chest-high saltwater. They were nothing more than the fish in the Japanese shooting barrel. The first thing Frank noticed was that it was nearly impossible to walk, that it was impossible to fire his gun, and although he was a human target for Japanese snipers in need of some early-morning target practice, Frank’s focus was on some very short-term goals: one foot forward, now the other foot. Keep gun above head so it doesn’t get wet. Now one more foot forward. This seemed like it took an hour or more (it took less than five minutes), and Frank kept wondering how it was that he was still alive. Dumbroski, a sergeant who had been the big, tough bully of the unit until this moment, was frozen in place, weeping. Keep moving. Leg. Foot. Rifle. Dry.

And then suddenly he was on the beach. A beach of black volcanic sand. Red blood on black sand made for an odd mixture; both caught the light of the morning sun and glistened with more life than they deserved. The brush of the jungle was just a few yards away and appeared to offer the best chance for cover from the incoming shells being fired from a cliff about a mile away. Within a couple hours most of the Marines had landed and the casualties were not as great as anticipated. The Japanese had decided not to fight this battle on the beach, perhaps because the Marines had set off enough smoke bombs so that the enemy had difficulty seeing the invading Americans.