Here Comes Trouble (39 page)

Read Here Comes Trouble Online

Authors: Michael Moore

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Philosophy, #Biography, #Politics

But now he wanted to tell me something. I had only known him at this point a few short months, and so the talk of “blood on my hands” was a bit shocking, and I was instantly uncomfortable.

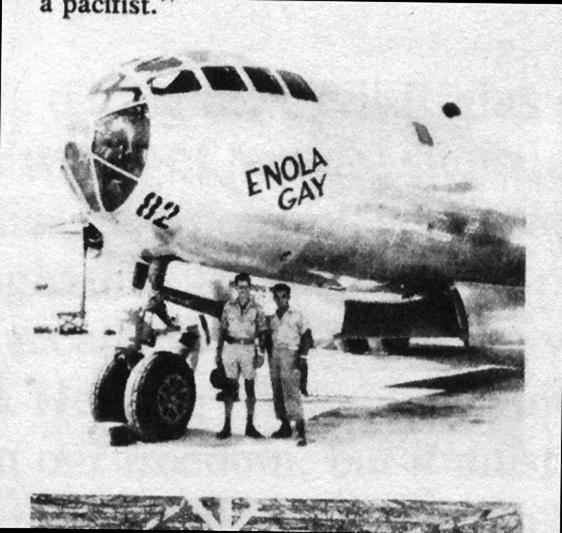

He pulled out an old photograph and pointed to it. In the center of the photo was a plane, and in front of the plane was a group of airmen. And in the middle of the airmen was a chaplain, a priest.

“That’s me,” he said, pointing at the much younger version of himself. “That’s me.”

He looked at me as if I were supposed to know something, or say something. I looked at him, confused and trying to understand what it was I was supposed to understand. It then struck me that he, like my dad, carried with him all the scars of that war. Just from being there, this good priest must have still felt that he was part of a lot of the death and dying. I understood.

“So you were in World War II,” I said sympathetically. “So was my dad. So much death and destruction. It must have been horrible to witness it. Where were you stationed?”

He continued to look at me as if I weren’t getting it.

“What does it say on the plane?” he asked.

I looked closely to see what the writing on the nose of the plane said.

Oh.

“Enola Gay.”

“Right,” Father Zabelka said. “I was the chaplain for the 509th on Tinian Island. I was their priest.”

And then he added: “On August 6, 1945, I blessed the bomb they dropped on Hiroshima.”

I took a deep breath, staring at the photo, then looking away, and then looking at him. His dark eyes seemed even darker now.

“I was the chaplain of the

Enola Gay.

I said Mass for them on August 5, 1945, and the next morning I blessed them as they left for their mission to slaughter two hundred thousand people. With my blessing. With the blessing of Jesus Christ and the Church. I did that.”

I didn’t know what to say.

He continued:

“And three days later, I blessed the crew and the plane that dropped the bomb on Nagasaki. Nagasaki was a Catholic city, the only majority Christian city in Japan. The pilot of the plane was a Catholic. And we obliterated the lives of forty thousand fellow Catholics, seventy-three thousand people in all.”

There was now a mist in his eyes as he told me of this horror.

“There were three orders of nuns in Japan, all based in Nagasaki. Every last single one of them was vaporized. Not a single nun from any of the three orders was alive. And I blessed that.”

I didn’t know what to say. I reached out and put my hand on his shoulder.

“George, you didn’t drop the bomb. You didn’t plan the destruction of these cities. You were there to do your job, to minister to the needs of these young men.”

“No,” he insisted, “it’s not that easy. I was part of it. I said nothing. I wanted us to

win.

I was part of the effort. Everyone had a role to play. My role was to condone it in the name of Christ.”

He explained that far from being repulsed when he heard the news about Hiroshima later that day, he felt what most Americans felt—relief. That maybe this would end the war.

“I didn’t quit over this,” he said emphatically. “I remained as a chaplain, even after the war, in the Reserves, and the National Guard. For twenty-two years. When I retired, I was a lieutenant colonel. Few chaplains achieve that rank.”

He then recounted how, a month after the two bombings, he joined the American forces as they entered Japan after the Japanese surrendered. He ended up in Nagasaki and saw firsthand the people who survived and the suffering they were going through. He found the headquarters, in rubble, of one of the orders of nuns. At the cathedral, he dug out the censer, the top half of it fully intact. He participated in the relief effort. It made his conscience “feel better.”

“But did you know on the morning of August sixth that the

Enola Gay

was going to drop that bomb? Did you even know what that bomb was?”

“No, we didn’t,” Zabelka said. “All we knew was that it was ‘special.’ We said it was ‘tricked up.’ Nobody had any idea that it had the capability to do what it did. The crew had special instructions, they knew not to look, and to get out of there as fast as possible.”

“Then if you didn’t know, you’re not responsible.”

“Not true!” he said firmly. “Not true! It is the responsibility of every human to know their actions and the consequences of their actions and to ask questions and to question things when they are wrong.”

“But George, this was war. No one is allowed to ask any questions.”

“And it’s exactly that kind of attitude that continues to get us into more wars—no one asking any questions, especially in the military. Blind obedience—we didn’t let the Germans get away with that excuse, did we?”

“But George, the difference was, we were the good guys, we were the ones who were attacked.”

“All true. And history is written by the victors. A good case can be made that the Japanese had already decided to surrender. We wanted to drop those bombs. We wanted to send a message to the Russians.”

He looked straight at me.

“You can say I didn’t know anything before Hiroshima, about what that bomb would do. But what about three days later? I knew then. I knew what would happen to the next city, which turned out to be Nagasaki. And yet I blessed… I blessed the bomb. I blessed the crew. I blessed the slaughter of seventy-three thousand people. God have mercy on me.”

George told me how in the mid-to-late sixties he had his “St. Paul moment” where he was “knocked off his horse” and he realized that the men in power were up to no good and that it will always be the poor who suffer. He decided to dedicate his life to total pacifism and became an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War in his Sunday sermons. He got involved in the civil rights movement in Flint. He was the very definition of a radical priest. He supported SDS, and when the Weathermen had their infamous War Council meeting in Flint in 1969, he opened up the doors of his church to the participants (who were all certainly not pacifists) so they’d have a place to sleep. He became known as the priest who wouldn’t back down, wouldn’t give in on matters of war and race and class. I had heard of Father Zabelka during all those years. I just never knew why he was the way he was. Now I did. And no matter how much he worked for peace, he could never

not be

the priest who “blessed the bomb.”

“I will have much to answer for when I meet St. Peter at those gates,” he said. “I am hopeful he will be merciful to me.”

I was grateful he told me his story and I wrote about it in my paper. He continued to help at the

Voice,

doing whatever menial tasks needed to be done, like dropping stacks of the paper off at locations in the north end of Flint.

Four years later, Father Zabelka decided it was time to perform further penance—and spread his gospel of peace. He began a walk across America to the Holy Land—a literal walk from Seattle to New York, then a plane ride over the ocean (he hadn’t perfected the walking-on-water bit), and then continuing on to Bethlehem. A total of eight thousand miles. And he did it in just over two years. At stops along the way he would tell the story of his transformation from pro-war atom bomb chaplain to hardcore pacifist.

When he returned, he stopped by the

Voice

one day, saying he wanted to see me.

“Michael, I’ve been thinking for some time and wondering why you left the seminary, why you didn’t go on to be a priest.”

“Well,” I said, “a number of reasons. I was only fourteen when I went. By fifteen, the hormones kicked in. Plus, I didn’t—and don’t—care for the institution and its hierarchy. And what the institution says it stands for has little to do these days with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

“Oh, and they also told me not to come back.”

Zabelka may have been a “radical priest,” but he was still a priest and still very faithful to the Catholic Church.

“I’ve been reading some of your comments about the Church and the Pope in the

Voice,

and I’m just worried about you. And your soul.”

I laughed. “George, you don’t have to worry about me or my soul. I’m doing just fine.”

“But it seems that you’ve left the Church.”

“Let’s just say I’m a recovering Catholic.”

That did not go over well.

“Would you do me a favor and pray with me right now?”

“Are you serious?”

“Yes. I just want to make sure you are going to be OK.”

“I’m going to be OK. And I pray when I need to.”

“Just say the Lord’s Prayer with me right now.” He began:

“‘Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name

…

’”

“George—stop. This isn’t necessary.”

“

. . . ‘

Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on Earth

…

’”

“

George! Stop!

This is creeping me out!”

“Don’t say that about the Lord’s Prayer, Michael,” he said, interrupting the Lord’s Prayer. “I think you need this.”

“I don’t need it. I don’t want it. And I don’t know what’s gotten into you.”

He became silent. He looked at me. He said nothing. I didn’t know what to say. The silence was excruciating.

“It’s important you carry on,” he said when he finally spoke. “It’s important to do what you do. But you can’t do it without the Church. You need the Church and the Church needs you. You need to go back to Mass. You need to find a place within the Church where you can find peace.”

I realized he was talking about himself. I realized that he still blamed himself for what happened on Tinian Island, and that were it not for the Church, for his faith, who knows what would have become of him. For every whipping he’d given himself over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he had the Catholic Church there to give him a chance to redeem himself. He was still a priest. He could still do good with that, and maybe in his mind, if he did enough good, he would be forgiven on Judgment Day. I looked at this old man and understood the demons he still carried with him. I wasn’t offended that he thought I needed some sort of “saving.” It was an easy thing to forgive him for.

I spoke.

“‘Give us this day our daily bread and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us, and lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil, forever and ever. Amen.’”

He smiled. “There. That wasn’t so hard, was it?”

“No, George,” I said kindly, “it wasn’t.”

“Good! Now, what do you want me to do for next week’s paper?”

A

BU

N

IDAL HAD A

C

HRISTMAS PRESENT

for me. He was going to kill me.

It wasn’t like he wanted to kill

me

specifically. It was more like we drew names. Or perhaps he was just planning a sick game of Secret Santa.

But he and I, for better or worse, had an unplanned rendezvous one morning during Christmas Week, 1985, at the Vienna International Airport.

And I lived to tell you about it.

Abu Nidal was the most feared terrorist in the world in the mid-’80s, the Osama bin Laden of his time. He was even feared by Yasser Arafat and the PLO. Having broken away from Arafat a decade earlier, Nidal formed the Fatah Revolutionary Council, or as he preferred to call it, “The Abu Nidal Organization.” Nidal believed Arafat to be too soft on Israel. He was opposed to any concessions whatsoever and believed that striking military targets was a waste of time—he thought all efforts should be aimed at civilians. He just wanted to kill Jews—and any Palestinians who wanted to sit down and negotiate with Jews. He was like that.

What led Nidal to this career path seemed evident in his childhood. His real name was Sabri al-Banna, and his father, Khalil al-Banna, was one of the richest men in Palestine, owning thousands of acres of fruit groves and exporting that fruit to Europe. It was said that 10 percent of the citrus fruit that went from Palestine to Europe came from the al-Banna family trees.

The British partitioning (such a polite word!) of Palestine and the subsequent creation of the Israeli state—and the various wars that followed—left the al-Bannas with next to nothing. As Sabri was the twelfth child of one of Khalil’s many wives, there wasn’t much left for him. In fact, when his father died, his mother was kicked out of the family, and Sabri was ostracized and pretty much left to fend for himself. This led to a series of abusive situations which made him a very angry boy—who then became a very angry young man who wanted a fruit tree or two returned to him.