Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (56 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

No sooner had Young arrived at Aqaba than he was to receive a further shock—instead of a neat chain of command in which Major Lawrence reported to Lieutenant-Colonel Dawnay and through Dawnay to theircommanding officer, Colonel Joyce, it was announced that Lawrence himself had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel, and been awarded the DSO for Tafileh (“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty”), so that he was now equal in rank to Alan Dawnay, and Young was put even more deeply in the shade. Lawrence later dismissed Young’s role, relegating him to taking over “the transport, and general quartermaster work,” but that is not how Young saw his job, then or later.

March or April 1918 (the exact date is uncertain) provided another irritation for Young in the form of the unexpected arrival of Lowell Thomas and Harry Chase. Young jumped to the conclusion that Lawrence had invited the two Americans to Aqaba in pursuit of publicity, whereas in fact they had been allowed to go there by Allenby. Indeed Allenby himself made the suggestion to Thomas at a luncheon in Jerusalem for HRH the duke of Connaught (the seventh child and third son of Queen Victoria), who had come to confer on Allenby “the Grand Cross of the Order of the Knights of Jerusalem.” The duke had hoped to decorate Lawrence too, but Lawrence took good care to be absent. It is a comment on Lowell Thomas’s Yankee persistence, affability, and effectiveness that he had managed to get himself invited to the luncheon, where he was encouraged to go to Aqaba. Thomas’s journey there would prove unexpectedly long and difficult—he and Chase “[sailed] fifteen hundred miles up the Nile into the heart of Africa to Khartum, and then across the Nubian Desert for five hundred miles to Port Sudan on the Red Sea, where we hoped to get accommodation on a tramp vessel of some sort.” Although Allenby had given his blessing to the expedition, he did not apparently feel obliged to provide transportation, since Thomas and Chase could have taken a train from Cairo to Port Suez, and then been accommodated comfortably on a supply ship or a naval vessel from Port Suez directly to Aqaba, a journey of only a few days. The benefit of the roundabout route was that it allowed the pair to record on film Luxor and Thebes, a sandstorm in Khartoum, a visit to “Shereef Yusef el Hindi … the holiest man in the Sudan” (whose desert library, Thomas assured his American readers, apparently with a straight face, contained a volume of speeches by Woodrow Wilson), and a trip across the Red Sea on a steamer loaded with horses, mules, donkeys, and sheep, and a crew consisting of “Hindus, Somalis, Berberines, and fuzzy-wuzzies.” At Aqaba, Thomas and Chase were sent ashore on a barge loaded with mules and donkeys, and when one of the donkeys “was kicked overboard by a nervous mule,” it was immediately torn apart and devoured by two gigantic sharks. Lowell Thomas was not the inventor of “the travelogue” for nothing—all these incidents would play a role in the lecture and film show that would make “Lawrence of Arabia” world famous, so it is perhaps just as well that Thomas and Chase were obliged to take the long way around. Only a few hours after the donkey had been eaten by the sharks, “Lawrence himselfcame down the Wadi Itm, returning from one of his mysterious expeditions into the blue.”

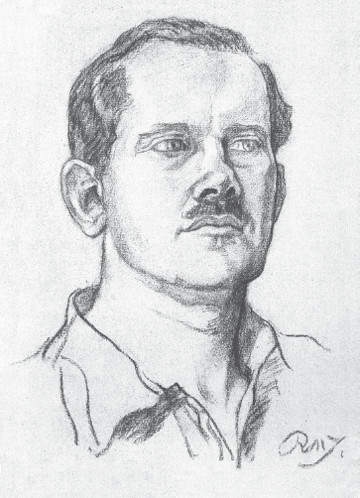

Young.

“To accompany Lawrence and his body-guard on an expedition was a fantastic experience,” Lowell Thomas would write in his best-selling book With Lawrence in Arabia, though he never actually did go on such an expedition. “First rode the young shereef, incongruously picturesque with his Anglo-Saxon face, gorgeous head-dress and beautiful robes. Likely enough, if the party were moving at a walking pace, he would be reading or smiling to himself over the brilliant satire of Aristophanes in the original. Then in a long, irregular column his Bedouin ‘sons’ followed in their rainbow-colored garments, swaying to the rhythm of the camel gait…. At either end of the cavalcade was a warrior poet. One of them would begin to chant a verse, and each man, all along the column, would take his turn to cap the poet’s words with lines of the same meter.”

This vision of the young “prince of Mecca,” engrossed in a volume of the Greek classics (in “the original” Greek, of course) as he and his colorful bodyguard ride across the desert on “one of his mysterious expeditions into the blue,” was one that Lowell Thomas would fix firmly in the popular mind—so firmly that even forty-four years later, when David Lean’s award-winning film Lawrence of Arabia was released to international acclaim, the Lawrence it portrayed still owed much to the colorful reporting of Thomas and the inspired photography of Chase. There is a considerable difference between Lawrence’s estimate of how much time Thomas spent with them and Thomas’s own account. Jeremy Wilson, in his authorized biography of T. E. Lawrence, writes that Thomas “spent less than a fortnight with Feisal’s army and saw Lawrence for only a few days.” This is surely correct, but it leaves out the intensity of the time Thomas and Chase did spend with Lawrence, and their determination to get as many photographs, reels of film, and interviews as they could, as well as Lawrence’s willingness to cooperate. Judging from the number of photographs Chase took (many of them artfully staged), and from Thomas’s voluminous notes, Lawrence was not only cooperative but enthusiastic; and in one of the photographs showing Lawrence and Lowell Thomastogether, Lawrence looks unusually relaxed and good-humored, not at all like a man being inconvenienced by two importunate Yankee journalists. Nor can Lawrence have been under any illusion that Lowell Thomas was going to write a series of thoughtful, fact-filled dispatches about the Arab army and the war in the Hejaz. Thomas was a showman, an inspired huckster in the tradition of P. T. Barnum, a lecturer who would prove every bit as successful as Mark Twain; and anybody meeting him, let alone someone as intelligent as Lawrence, would have known all that about him in five minutes or less. As for Chase, he was a Hollywood cameraman, not a documentary filmmaker—his job was to put glamour on film. Lawrence himself may have enjoyed pulling the leg of the gullible American, but if so, the American had the last laugh. Thomas may or may not have believed everything he was told, but in either case he managed to sell it, burnished with his own additions, exaggerations, romantic touches, and flamboyant prose, to an audience of millions.

With Lawrence in Arabia is artfully written; it suggests that Thomas was an eyewitness to Lawrence’s desert operations, without actually saying so, a familiar journalistic trick. Lawrence himself wrote Thomas out of Seven Pillars of Wisdom altogether, and later made it clear that Thomas “was never in the Arab firing line, nor did he ever see an operation or ride with me.” There is no question, however, that Lawrence posed for innumerable staged photographs then and later on, including one in which he is claimed to be lying in the sand beside his kneeling camel’s neck, holding his Lee-Enfield rifle at the ready, a bandolier of.303 cartridges around his neck, as if there were Turks on the horizon. In another he (or somebody else) appears disguised, his face covered with an embroidered flowered veil, as “a Gypsy woman of Syria,” in which costume he planned to go behind the enemy lines to spy out information—something Lawrence actually did later on. Oddly enough, Thomas went to some trouble to deny that Lawrence cooperated with Chase in these carefully staged pictures. “My cameraman, Mr. Chase,” Thomas wrote, “uses a high-speed camera. We saw considerable of Colonel Lawrence in Arabia, and although he arranged for us to get both ‘still’ and motion pictures of Emir Feisal,

Auda Abu Tayi, and the other Arab leaders, he would turn away when he saw the lens pointing in his direction…. Frequently Chase snapped pictures of the colonel without his knowledge, or just at the instant that he turned and found himself facing the lens and discovered our perfidy.”

Nobody looking at Chase’s photographs of Lawrence could possibly believe this story. They are not casual “snaps"; they are quite clearly well-thought-out formal portraits or carefully faked “action” scenes, for which the subject’s willing cooperation would have been essential; and in fact Lawrence would pose for more of them later on, in London, where studio lighting and a backdrop were required. It suited both Thomas and Lawrence to pretend that Lawrence was the unwitting victim of the photographer—from Thomas’s point of view, it made the whole story more of a scoop; and from Lawrence’s, it freed him from the accusation of seeking publicity—but it cannot be true.

Feisal, whose understanding of the value of American publicity was a good deal sharper than Lawrence’s, played the good host, taking Thomas and Chase on a long trip out into the desert—providing more good footage for Chase of camels, Bedouin, and tents—and sent them on an excursion to Petra, “the rose-red city, half as old as Time,” where Thomas wondered whether “we had not been transported to a fairy-land on a magically-colored Persian carpet.” Chase’s pictures would later appear in Lowell Thomas’s show about Lawrence, as well as in future travelogues.

Everybody seems to have been aware of just how important it was to present a positive picture of the Arab Revolt to America. Thomas got Clayton and Hogarth to talk to him about Lawrence, despite the fact that as senior intelligence officers they might have kept their mouths shut. Thomas also interviewed people at Aqaba, where everybody may have embellished stories about Lawrence for Thomas’s benefit. Bedouin tribesmen, many of whom believed that the Koran forbade photography, since it involved making a human image, nevertheless meekly allowed Chase to take their pictures, and Feisal provided masses of horsemen and camel riders, banners flowing and swords drawn, for action crowd scenes. Whether Lawrence was conscious of it or not, the few days hespent with Lowell Thomas and Harry Chase in Aqaba would eventually be instrumental in creating the legend of “Lawrence of Arabia.”

Lawrence may not have realized that he had launched himself on a collision course with a new and potent combination of tabloid newspapers, press photography, and the cinema, but what he did in those few days at Aqaba would change his life far more than the mere acceptance of a few decorations and medals could have done. He had the good fortune—or perhaps the bad luck—to put himself in the hands of one of the most gifted and silver-tongued promoters of the twentieth century, a man who would be a star in media not even invented yet, and who would live on to 1981: a long life devoted to making himself and Lawrence household names.

It was at about this time, after Lawrence had left Thomas and Chase to continue their interviews and filming without him, that he rode north to Shobek, about twenty miles from Petra, and learned there of the death of Daud, the friend of Farraj, one of his two high-spirited servant boys. Farraj himself came to Lawrence with the news that Daud had frozen to death at Azrak.

*

In Lawrence’s account of this, in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, there is a clear change of mood, as if some of the exuberance and joy he had felt in his relationships with the Arabs was being squeezed out by the war. Fearless as he may have been for himself, Lawrence was not indifferent to the death of others, particularly those whom he loved, or for whom he felt responsible. He wrote of Farraj and Daud that they “had been friends from childhood, going about hand in hand, for the happiness of feeling one another, and diverting our march by their eternal gaiety.” He reflected on the “openness and honesty in their love, which proved its innocence; for with other couples we had seen how, when passion had thrust in, it had not been friendship any more, but a half-marriage, a shamefaced union of the flesh.” The relationship between Daud and Farraj leads Lawrence on to another of those curious speculations about sexuality, which occasionally puzzle the reader of Seven Pillars of Wisdom and make it clear that Lawrence’s ideas about heterosexuality were a strange mixture of innocence, idealism, his mother’s disapproving eye for the slightest sign of sexual arousal, and the awful example (from Lawrence’s point of view) of Thomas Lawrence’s having given up his fortune and place in society out of lust for his daughters’ governess. “European women,” Lawrence wrote, “were either volunteers or conscientious objectors in this war to govern men’s bodies,” whereas, “in the Mediterranean, women’s influence and supposed purpose were circumscribed and the posture of men before her sexual.”

It is hard to unravel exactly what this means, but it clearly ties in with Lawrence’s assumption that women endured sex unwillingly in the European world, where as in the East “all the things men valued—love, companionship, friendliness—became impossible heterosexually, for where there was no equality there could be no mutual affection.” Of course Lawrence judged eastern domestic life as an outsider, whose relationship with the Arabs was either at work in Carchemish, or at war, when they were far from home. Much as he liked to think he had become part of their lives, he was still excluded from what went on between husband and wife (or wives) and from gauging the degree to which Arabs were invisibly influenced by women or by the demands of domestic life. All that, in the Arab world, took place behind a curtain, but the intrigues of the wives and concubines of the Turkish sultan, and the degree to which a woman of the harem might conspire to put her own son on the throne in place of another, should have cured Lawrence of the notion that women in the East were necessarily without ambition, interest, or influence in public or business affairs, or always submissive to their husband. King Hussein may have been an imposing, if infuriating, figure, but who knows what his four wives had to say to him about the relative positions of their sons when he stepped behind the closed door of his private apartments? The voices of women went largely unheard in the Middle East until very recently in its history, but this does not mean that they did not have ways to make themselves heard in private, or that men did not seek theiradvice, approval, or judgment, as they do elsewhere—or did not have to endure the relentless questioning of a strong-willed mother, as Lawrence himself did. The notion that male Arab society provided a “spiritual union,” which complemented “carnal marriage,” and that “these bonds between man and man [were] at once so intense, so obvious, and so simple,” is a nice tribute to Daud and Farraj, but a very doubtful generalization about marriage in the East, which, while it is certainly different in many ways from marriage in the modern, industrialized West, is perhaps not as different as outsiders may suppose.