Hervey 09 - Man Of War (3 page)

Read Hervey 09 - Man Of War Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

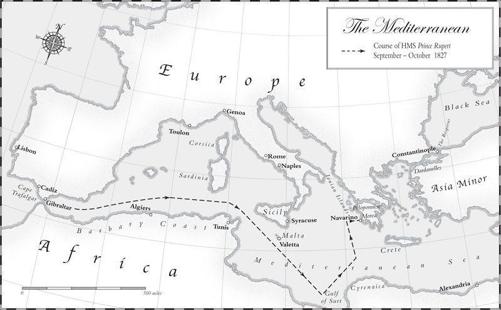

Now, however, in 1827, two decades after Trafalgar, the pendulum of military fortune was swinging back: it was His Majesty’s ships that would again make war in the cause of peace and of liberty; the slave trade was being vigorously suppressed, and a triple alliance of Britain, France and Russia would oblige the Turks to quit Greek waters – the very cause for which Byron had died in the Peloponnese, and which philhellenes throughout Europe had long promoted. The Royal Navy was at last resurgent. Men like Matthew Hervey’s friend Captain Sir Laughton Peto, who had thought themselves beached, would have their chance once more.

But what of those in red coats? There were certainly far fewer of them than at any time in the life of all but the most grey-haired. Many were gaining a good dusting in far-flung corners of the growing empire; Hervey’s own uniform, though blue not red, had had a good dusting in India, and of late in the Cape Colony. But the growing use of the army to police the nation’s agrarian, industrial and political unrest made the cavalry unwelcome in some quarters (‘Peterloo’ was on the lips of many a rabble-rouser yet, and in the pages of the radical press). And when the explosive element of Catholic emancipation was added, coupled inextricably as it was with the condition of Ireland, society at times looked distinctly brittle. The old order was changing; the statesmen and soldiers who had brought Bonaparte to his knees and had managed to keep a lid on the unrest during the economic depression that followed were passing. New men gilded the ancient games.

This, then, is Matthew Hervey’s world, simple soldiering no longer his refuge. Family and friends are become equally a source of comfort and of disquiet. His future is on the one hand settled and propitious; on the other, uncertain and discouraging:

Thoughts of great deeds were mine, dear Friends, when first

The clouds which wrap this world from youth did pass . . .

And from that hour did I with earnest thought

Heap knowledge from forbidden mines of lore.

Shelley

I

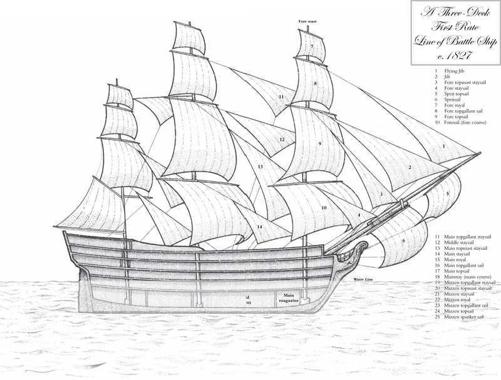

A FIRST-RATE COMMAND

Gibraltar, 28 September 1827

The barge cut through the swell with scarcely a motion but headway – testament to the determination with which her crew was bending oars. In the stern sat Captain Sir Laughton Peto RN, his eyes fixed on their objective, His Majesty’s Ship

Prince Rupert

– glorious sight against the backdrop of the Rock. To Peto’s mind

Rupert

was in no measure diminished by the towering crag; her three decks, her lofty masts, somehow outsoared the shadow of that Pillar of Hercules. Neither were her batteries belittled by those of the massive Montague Bastion, which Peto himself had only lately quit. Impregnable as was the citadel-Rock,

Rupert

was yet the most powerful of His Majesty’s ships at sea, a floating fortress able to send any of the King’s enemies to the bottom, as her forebears had done two decades earlier (and not many leagues to westward).

Any

ship of the Royal Navy would look admirable at anchor in Gibraltar Bay, reckoned Peto: the Rock and the ‘Nelson chequer’ were as perfect a unity as any he could think of. As perfect as if they had been in Plymouth Sound, at Spithead, the Nore, or at Portsmouth. And Peto had been intent on nothing but the great three-decker from the moment he stepped into his barge.

She was an arresting picture, to be sure, but neither did it do for a captain, especially one of his seniority, to have eyes for so mere a thing as a boat’s crew; his attention must be on more elevated affairs than a midshipman and a dozen ratings. Above all, though, it was opportunity to study his new command as an enemy might. Peto was acquainted by reputation with her sailing qualities, but how might another, impudent, man-of-war’s captain judge her capability? He fancied he might know what a Frenchman would think. That mattered not these days, however; it was what a Turk thought that counted, for a year ago the Duke of Wellington, on the instructions of the foreign secretary, Mr Canning, had signed a protocol in St Petersburg by which Russia, France and Great Britain would mediate in the Greeks’ struggle for independence; and increasingly that protocol looked like a declaration of war on the Ottoman Turks.

What a mazy business it all was too: the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, on his sickbed for months, and in April the King sending for Canning to form a government, in which many including the ‘Iron Duke’ then refused to serve; and now Canning himself dead and the feeble Goderich in his place. Peto did not envy Admiral Codrington, the commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, whose squadron he was to join: how might the admiral do the government’s will in Greek waters when the government itself scarcely knew what was its will? He could not carp, however, for he was the beneficiary of that uncertainty: soon after

Rupert

had left Portsmouth, where formerly she had been laid up in Ordinary, their lordships at the Admiralty had sent a signal of recall to her captain (and promotion to flag rank), followed by an order for him, Peto, to proceed at once to Gibraltar to take command in his stead.

The wind was strengthening. Peto did not have to take his eyes off his ship to perceive it. Nor did he need to crane his neck to mark the frigate-bird that accompanied them, tempting a prospect though such an infrequent visitor was – and sure weather vane too, for he had frequently observed how the bird preceded changeable weather, as if borne by some herald of new air. With a freshening westerly it would not be long before

Rupert

could make sail; and he willed, unspoken, for hands to pull even smarter for their wooden world –

his

wooden world.

He had waited a long age for this moment, for command of a first-rate; waited in fading expectation. Well, it were better come late than never. And so now he sat silent, perhaps even inscrutable (he could hope), in undress uniform beneath his boatcloak: closed double-breasted coat with fall-down collar, double epaulettes for his post seniority, with his India sword hanging short on his left side in a black-leather scabbard; and within a couple of cables’ length of another great milestone of his nautical life.

At their dinner at the United Service Club (when was it – all of six months ago?) he had told his old friend Major Matthew Hervey of the 6th Light Dragoons that he was certain another command would not come: ‘There will be no more commissions. I shan’t get another ship. They’re being laid up as we speak in every creek between Yarmouth and the Isle of Wight. I shan’t even gain the yellow squadron. Certainly not now that Clarence is Lord High Admiral.’ For yes, he had been commodore of a flotilla that had overpowered Rangoon (he could not – nor ever would – claim it a great victory, but it had served), and he had subsequently helped the wretched armies of Bengal and Madras struggle up the Irawadi, eventually to subdue Ava and its bestial king; but it had seemed to bring him not a very great deal of reward. The prize-money had been next to nothing (the Burmans had no ships to speak of, and the land-booty had not amounted to much by the time its share came to the navy), and KCB did not change his place on the seniority list. Their lordships not so many months before had told him they doubted they could give him any further active command, and would he not consider having the hospital at Greenwich?

But having been, in words that his old friend might have used, ‘in the ditch’, he was up again and seeing the road cocked atop a good horse. The milestones would come in altogether quicker succession now.

And what a sight, indeed, was

Rupert

! Even with sail furled she was the picture of admiralty: yellow-sided, gunports black – the ‘Nelson chequer’; and the ports open, too, of which he much approved, letting fresh air circulate below deck; and the crew assembling for his boarding (he could hear the boatswain’s mates quite plainly). What could make a man more content than such a thing? He breathed to himself the noble words:

gentlemen in England, now abed, will think themselves accurs’d they were not here

.

There was

one

thing, of course, that could make a man thus content: the love, the companionship at least, of a good woman (he knew well enough that the love of the other sort of woman was all too easy to be had, and the contentment very transitory). And now he had that too, for in his pocket was Miss Hervey’s letter.

Why had he not asked for her hand years ago? That was his only regret. He felt a sudden and most unusual impulse: he wished Elizabeth Hervey were with him now. Yes, in this very place, at this very moment; to see his ship as he did, to appreciate her lines and her possibilities –

their

possibilities, captain and his lady. Oh, happy thought; happy, happy thought!

They closed astern of

Rupert

– Peto could make out her name on the counter quite clearly now – and he fancied how he might see Elizabeth’s face at the upper lights in years to come. When first he had gone to sea, a lady might have stood at the gallery rail, but galleries had fallen from fashion. A pity: he had always loved their airy seclusion. The Navy Board was now building ships with rounded sterns, and sternchasers on the upper decks (Admiral Codrington flew his flag in one of these, the

Asia

). And about time, too, was Peto’s opinion, for a stronger stern and a decent weight of shot to answer with made raking fire a lesser threat. But in his heart he was glad to have command of a three-decker of the old framing: she was much the finer looking (in truth, his own quarters would be the more commodious too); and he certainly had no intention of allowing any ship to cross his stern.

His cloak fell open, and in pulling it about himself again he noticed his cuff: Flowerdew would be darning it within the month. But that should be of no concern to him. He was not – never had been – a dressy man. If the officers and crew of His Majesty’s Ship

Prince Rupert

did not know of his character and capability then that was their lookout: no amount of gold braid could make up for reputation. His service with Admiral Hoste, his command of the frigate

Nisus

, his time as commodore of the frigate squadron in the Mediterranean, and lately his command of

Liffey

while commodore of the flotilla for the Burmese war – these things were warranty enough of his fitness for command of the

Rupert

.

Not that it was any business of the officers and crew: he, Sir Laughton Peto KCB, held his commission from the Lord High Admiral himself. These things were not to be questioned, on pain of flogging or the yard-arm. Except that he considered himself to be an enlightened captain, convinced that having a man do his bidding willingly meant that the man did it twice as well as he would if he were merely driven to it. Though, of course, it was one thing to have a crew follow willingly a captain who was everywhere, as he might be in a frigate, but quite another when his station was the quarterdeck, as it must be with a line-of-battle ship.

Nisus

had but one gun-deck; in action the captain might see all.

Rupert

had three, of which the two that hurled the greatest weight of shot were the lower ones, where the gun-crews worked in semi-darkness, and for whom in action the captain was as remote a figure as the Almighty Himself. The art of such a command, he knew full well, was in all that went before, so that the gun-crews had as perfect a fear of their captain’s wrath – and even better a desire for his love – as indeed they had for their heavenly maker. If that truly required the lash, he would not shrink from it, but at heart he was one with Hervey in this: more men were flattered into virtue than were bullied out of vice. Besides, in these days of peace, the press gang and assize men were no more: the crew were volunteers. The old ways had gone.