Hervey 09 - Man Of War (37 page)

Read Hervey 09 - Man Of War Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

He thought of going about the decks again, but it would have looked strange, perhaps making him appear uneasy. No, he would have to leave it to the lieutenants to keep the crew from torpor. Doubtless some of them would be thinking he had cleared for action too soon; and with four hours’ inactivity, and no enemy ship within sight, they had some cause. But he was ever of the opinion that it was not possible to clear too soon for action: there was a sort of superiority that came with taking the initiative, rather than having the enemy drive the business. What was an early rouse and cold food compared with knowing all was ready when the enemy hove in view?

‘Cutter ahoy, sir!’

Peto sighed with relief.

Lambe, coming up the companion ladder from yet another inspection below, barked the order without missing a step: ‘Mr Corbishley, the gangway if you please!’

‘Ay-ay, sir!’ The midshipman sounded pleased to have something to do at last.

They had not taken the gangway to the hold when they cleared for action, anticipating its imminent need. Midshipman Corbishley and the boatswain’s mates could have it rigged in ten minutes or so, lashing the frame to the ship’s side at the entry port on the middle deck, and then lowering the end to the waterline. Peto would have the women descend quickly and with all modesty to the cutter (rather than have them clamber down the side-ladder). It was something of an irony, as the whole crew knew: modesty had not been a mark of their time on board.

Except for Rebecca Codrington (and her maid). There was not a midshipman – and a good many lieutenants – who had not in some measure lost his heart to her. Indeed, she had somehow endeared herself to those before the mast too, for one of the hands was sent to the foot of the quarterdeck ladder with a present of a brightly coloured parrot in a cage, and a sentiment carved on a wooden tag: ‘Health to our Admiral’s Daughter’.

Peto made a mental note for his log, and with considerable relief:

Two bells of the Afternoon Watch, Miss Codrington and ship’s women transferred to cutter Hind

.

Rebecca stood in her brown cloak taking the sun, exchanging quiet words with her maid, understanding that the usual pleasantries with the occupants of the quarterdeck were necessarily curtailed in a ship cleared for action. She marvelled at

Rupert

’s transformation. The captain’s cabin, in which she had enjoyed the most attentive of company, where she had been extended every courtesy, as if she had been a grown woman, which to her own mind she was in all respects but that which she could not yet know (which did not in truth disbar her from that claim, for such knowledge was by no means given to all), was no more: it was now but a fighting station, as the rest of the ship, with rude-looking men gathered about the guns, where before there had been gentler faces, gold lace, and quiet-spoken servants. These men by no means repelled her; quite the opposite, indeed, for she saw in them the very safeguard of the nation, and of the ship and the fine officers she had come to know (and the finest of men that was the captain) – and most particularly of her father’s reputation. How, therefore, could she not admire – love, even – these men who held their life at his disposal? The thought made her blood run fast. And when Peto bid her farewell a final time her face was suffused with a colour he had never before seen in a female.

‘Miss Codrington, you are unwell?’

She smiled at him with the satisfaction of one who knew something her superior did not. ‘I am very well indeed, Captain Peto. Only that I have no desire to leave your ship.’

Peto returned the smile, indulgently. ‘Nor would any of us wish your leaving, Miss Codrington, but as you will understand, it will be no place for a female heart, erelong.’

Rebecca smiled once more. Had not a female once denied she had the heart of a woman, but of a prince of England – and declared it so on the fighting deck of an English ship? But Captain Peto was so admirable a man that she could not fence with him thus – not at least in the hearing of his own officers. ‘You are very good, sir.’

Hind

was turning in to starboard. Midshipman Pelham, whom Peto had detailed to see Rebecca safely down, stepped forward smartly and saluted.

But that had been earlier; there was nothing pressing on the captain’s attention now. ‘I shall accompany Miss Codrington myself, Mr Pelham.’

‘Ay-ay, sir.’ The voice betrayed only as much disappointment as the midshipman dared – which was but a very little.

Hind

ran in alongside with exemplary ease. It was, after all, a fleet cutter’s purpose to dart from ship to ship thus. She had been built to overhaul smugglers, and rigged to outmanoeuvre the handiest of them. Her master, a stocky man, a lieutenant perhaps not yet thirty, but with a wide, honest face – a man who might look useful in a boarding party – leapt for the gangway and came up briskly to the entry port. Seeing

Rupert

’s captain waiting for him at the top, rather than the midshipman he had expected, he saluted him, rather than the quarterdeck, just in time (for Peto’s humour was sorely tried by the business). He quickly regained his poise, however, smiling with such manifest cheer that Peto was at once deflected from any rebuke over the tardiness of his arrival. Indeed, having watched him handle the cutter, Peto was at once assured that he could perfectly entrust the admiral’s daughter – and the ship’s women – to such an active and engaging man as he.

‘Robb, sir. The admiral’s compliments, and would you be so good as to read these supplementary orders.’ The lieutenant held out an oilskin package.

As Peto took it, there was a single cannon shot from the

Asia

. He stepped out onto the gangway for a better look. The flagship firing thus meant but one thing: she drew attention to an imperative flag signal. He cursed, thinking that his lookouts had not seen it.

Lieutenant Robb at once had his telescope to his eye. Peto’s was on the quarterdeck, which made him crosser still – not that he could have been expected to read the commander-in-chief’s signals without a codebook.

Robb could, however (as commander of

Asia

’s tender he had a thorough acquaintance with the codes; cutting about the fleet, he lived by them, indeed). ‘ “Prepare to enter”!’

The next second, Robb was saluting again and taking his leave.

Peto’s mouth fell open. ‘Avast there, Mr Robb!’ he spluttered. ‘Where do you go? Take the women down, sir! I’ll read my orders first, damn it! They may require an answer!’ (though what answer was needed when the admiral signalled ‘prepare to enter’ he would have been hard put to suggest).

Robb looked puzzled. ‘Sir, with respect, I cannot now take off anyone with the flag signalling action. I am the flagship’s tender. My place in action is alongside her.’

‘Mr Robb, your orders were – were they not? – to take off the admiral’s daughter!’

‘Sir, with the very

greatest

respect, my orders were to give such assistance as I might, but the admiral’s signal is general to the fleet. As tender I must return at once.’

Peto’s face turned as red as the marine sentry’s jacket next to him, as if he would explode with all the violence of a carronade.

But he did not explode – just as if the gunner had stopped the flint with his hand. For he knew he would do the same as Robb were

he

master of the flagship’s tender.

Hind

was Codrington’s Mercury after all. The admiral would have need of this young officer and his cutter almost as much as he would have need of his flag lieutenant.

From the corner of his eye he could see the line of women, Rebecca and her maid at the head, for all the world like passengers on a packet come into Dover harbour. He sighed, but to himself (he would reveal nothing more of his dismay). ‘Very well, Mr Robb, but you will wait until I read through my orders!’

‘Ay-ay, sir!’ Robb was astute enough to know that a minute or so would make little difference to him, but in the circumstances a very great deal to a post-captain’s pride.

Peto opened his orders and read them rapidly. ‘No reply necessary,’ he growled, refolding them. ‘Good luck to you, Mr Robb. You may dismiss.’

Robb looked relieved. ‘Ay-ay, sir. And good luck to your ship too.’ He saluted again, adding cheerfully, ‘We shall next meet in the bay, I imagine, sir.’

Peto nodded, then watched him scuttle down the gangway, recollecting his own youthful, even carefree commands, before resolutely turning inboard.

‘Miss Codrington, ladies,’ he began, gravely but with every appearance of easy confidence, ‘I am obliged to offer you the continuing hospitality of my ship. Mr Corbishley, you are to escort Miss Codrington to the purser’s quarters; and,’ glancing at the boatswain, ‘Mr Mills, have the ladies conducted to the surgeon’s.’ He would have them all safely confined to the orlop deck, below the waterline, but at different quarters: if he could not get Rebecca Codrington off, he could at least keep her from the company of the ship’s women – whose conduct was certain now to be the ruder.

‘Ay-ay, sir.’

He turned once more to Rebecca. ‘Miss Codrington, you will be perfectly safe, no matter what the action on deck.’ Which was without doubt true unless there was a catastrophic explosion. He cleared his throat once more, as if something did genuinely inhibit what he would say. He bowed. ‘Until . . . until we are anchored at Navarino, then.’

Rebecca curtsied, but before she could reply, Peto had turned.

‘Make sail!’ he boomed, striding for the companion ladder as if with no thought in his mind but to close with the Turk.

XVII

THE UNTOWARD EVENT

A quarter of an hour later

‘Full and by, Mr Lambe.’

‘Ay-ay, sir,’ replied the lieutenant. ‘Full and by, Mr Veitch.’

‘Full and by, ay-ay, sir!’ replied the quartermaster, through teeth clenched on unlit pipe.

With a full course set, and studding-sails low and aloft, he would have his work cut out.

‘Very well, Mr Lambe, the admiral’s orders . . .’ Peto turned and advanced to the weather rail, more symbolic of privacy, now, with so many men at the quarterdeck guns. ‘Codrington intends entering the bay,

Asia

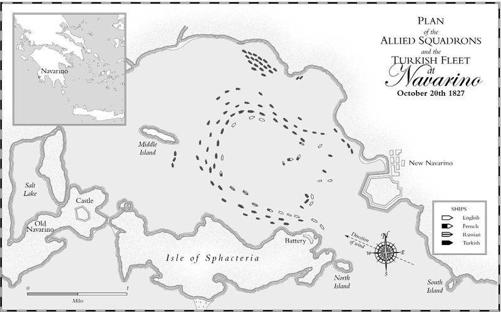

leading, then the French and after them the Russians. You will recall that the Turks – and when I say Turks I mean also the Egyptians – are drawn up in a horseshoe.’

Lambe nodded.

‘The fleet will anchor alongside the Turks exactly as I described. As you perceive, Codrington no longer wishes

Rupert

to stand off but to take station in the entrance to the bay to suppress the shore batteries on either side if they open fire. I can only conclude thereby that he believes it will assuredly come to a fight.’

Lambe nodded again, gravely. The entrance to the bay was not a mile wide:

Rupert

’s guns would play very well with the forts, but any half decent shore battery would have their range with the first shot.

‘Codrington’s advice is that the fort at New Navarin, to starboard, is the stronger. There’s a small, rocky islet to larboard which masks the fort on Sphacteria. If there were time we might first deal with Navarin and then Sphacteria, but I suspect we shall have no choice but to engage both at once, since the admiral will wish to close with the Turkish ships without delay if the forts signal any resistance. There are fireships, too.’

Lambe looked even more grave. ‘A regular powder keg, sir.’

‘Just so. We will take station now behind the flag, with

Genoa

abaft of us.’

‘Ay-ay, sir.’

Peto put his glass to his eye to see if

Asia

was signalling anew, but her main-mast halyard bore the same as before. Codrington was evidently standing well out to give the French and Russian squadrons time to catch up before turning for the bay.

The marine sentry struck the half hour – six bells.

‘Very well, Mr Lambe: secure guns, and have the boatswain pipe hands to dinner.’

‘Ay-ay, sir!’

Flowerdew advanced with a silver tray and coffee. There were two cups, as always (except when Rebecca had been on deck, when there were three), in case the captain wished to take his coffee with another. But Peto chose not to be sociable at this moment.